Vaster than empires, and more slow. And while thy willing

advertisement

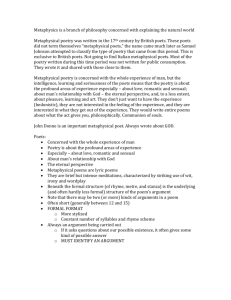

The English Baroque (Metaphysical Poets) 1603-1625: James I (Stuart); the coming of the Baroque for a time high Renaissance and early Baroque styles coexist (Shakespeare wrote his great tragedies in James I's reign; Donne wrote his elegies, satires and some last poems in the last decade of Queen Elizabeth's) Baroque style in poetry: 1. abounds in conceits* (elaborately sustained metaphor), unusual similes and puns; 2. there is a tendency to manipulate time and exploit its paradoxes; 3. dramatic situation of the poem: interaction betw. speaker, audience and reader; 4. baroque world-view: poetry often attempts to span the entire range between religious sentiment and libertinage, beauty and ugliness, egocentricity and impersonality, temporality and eternity. These issues were presented with immediacy by the political, religious and scientific events of the 17th century. *”A conceit is a comparison whose ingenuity is more striking than its justness, or, at least, is more immediately striking. All comparisons discover likeness in things unlike: a comparison becomes a conceit when we are made to concede likeness while being strongly conscious of unlikeness . . . . In a metaphysical poem, the conceits are instruments of definition in an argument, or instruments to persuade as opposed to mere decorations. The poem has something to say which the conceit explicates or something to urge which the conceit helps to forward.” (Helen Gardner, 'Introduction' to The Metaphysical Poets, 1957.) Copernicus (1473-1543); Galileo (1564-1642); Giordano Bruno (1548?-1600); Francis Bacon (1561-1626): challenge on traditional assumptions - increase in scepticism, introspection, self-consciousness and self-criticism And new philosophy calls all in doubt: The element of fire is quite put out, The sun is lost, and the earth, and no man's wit Can well direct him where to look for it. And freely men confess that this world's spent, When in the planets and the firmament They seek so many new; they see that this [world] Is crumbed out again to his atomies. 'Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone; All just supply, and all relation: Prince, subject, father, son, are things forgot, For every man alone thinks he hath got To be a phoenix, and that these can be None of that kind of which he is, but he. (Anatomy of the World) literary signs of a the world in transition: growing emphasis on satire and realism, introspection and psychological analysis, corresponding style: short, concentrated, colloquial and witty poems prominence of new genres: love elegy, epigram, verse epistle, dramatic monologue, meditative religious lyric and country-house poem Major poets of the early 1600s: John Donne and Ben Jonson John Donne (1572-1631) (Except the Anniversaries and a few minor pieces) his poems were not published in his lifetime, uncertainty about dating the poems (first edition in 1633) 3 main periods of his career: 1592-1601 from his arrival in London to his marriage; 1601-1615 from his marriage to his ordination; 1615-1631 from his ordination to his death 1. Satyres and Elegies and probably a good many of the Songs and Sonets = love poetry 2. Anniversaries: An Anatomy of the World and Of the Progress of the Soule, the first religious poems as well as further pieces of Songs and Sonets = miscellenous and occasional poems and verse-letters 3. some of the Holy Sonnets, and the rest of the Divine Poems as well as the sermons and other religious writings = religious poems directness and familiar tone of speech (immediacy and colloquial language) are the most striking features; fusion of passionate feeling and logical argument, extraordinary range of ideas and experience with startling connections between them Donne's poems: intense dramatic monologues in which the speaker's ideas shift and evolve from one line to the next - corresponding prosody: variable and jagged rhythm of colloquial speech ("Donne, for not keeping the accent deserved hanging" Ben Jonson) basic method: conceit (extended metaphor or extreme analogy), in which dissimilar concepts, objects or ideas are used to express thoughts and feelings. Because ideas from all realms, esp. religion, science and philosophy, were used in this poetry it was termed "metaphysical" by Dryden "He affects the metaphysics, not only in his satires, but in his amorous verses, where nature only should reign; he perplexes the minds of the fair sex with the nice speculations of philosophy, when he should engage their hearts, and entertain them with softness of love". (John Dryden of Donne /1693/) Songs and Sonets: cornerstone of his reputation despite the title, they directly challenge the Petrarchan sonnet sequences of the 1590s new sexual realism, introspective psychological penetration and a wide range and variety of mood there is no consistent philosophy of love; some poems are cynical, brutal or humorously worldly: The Flea, The Indifferent ecstatic and passionate: The Sunne Rising, The Dreame, The Good-morrow, Elegy 19.To His Mistress… fulfilment and happiness in love: A Nocturnal upon S.Lucies day the relationship of physical to spiritual love: The Ecstasy Come, madam, come, all rest my powers defy, Until I labor, I in labor lie. The foe oft-times having the foe in sight, Is tired with standing though he never fight. Off with that girdle, like heaven's zone glistering, But a far fairer world encompassing. Unpin that spangled breastplate which you wear, That th' eyes of busy fools may be stopped there. Unlace yourself, for that harmonious chime Tells me from you that now it is bed time. Off with that happy busk, which I envy, That still can be, and still can stand so nigh. Your gown, going off, such beauteous state reveals, as when from flowry meads th' hill's shadow steals. Off with that wiry coronet and show The hairy diadem which on you doth grow: Now off with those shoes, and then safely tread In this love's hallowed temple, this soft bed. In such white robes, heaven's angels used to be Received by men; thou, Angel, bring'st with thee A heaven like Mahomet's Paradise; and though Ill spirits walk in white, we easily know By this these angels from an evil sprite: Those set our hairs on end, but these our flesh upright. License my roving hands, and let them go Before, behind, between, above, below. O my America! my new-found-land, My kingdom, safeliest when with one man manned, My mine of precious stones, my empery, How blest am I in this discovering thee! To enter in these bonds is to be free; Then where my hand is set, my seal shall be. Full nakedness! All joys are due to thee, As souls unbodied, bodies unclothed must be To taste whole joys. Gems which you women use Are like Atlanta's balls, cast in men's views, That when a fool's eye lighteth on a gem, His earthly soul may covet theirs, not them. Like pictures, or like books' gay coverings made For lay-men, are all women thus arrayed; Themselves are mystic books, which only we (Whom their imputed grace will dignify) Must see revealed. Then, since that I may know, As liberally as to a midwife, show Thyself: cast all, yea, this white linen hence, Jöjj, hölgyem, jöjj és vetkőzz le velem, vágy kínoz, mikor nem szeretkezem. S mint harcos, ha ellenségre talál: lándzsám megfájdul, mert nem döf, csak áll. Öved délkörét oldozd meg hamar: minden tájnál szebb földövet takar. Pruszlidat vesd le, olyan feszesen tapad; más nem lát bele, de nekem hadd suttogja a susogó selyem esése, hogy most lefekszel velem. Fűződre régtől féltékeny vagyok, de megnyugtató, mikor kikapcsolod. Oly szép vagy, ha ruhád leengeded: kibukkanó nap nyári kert felett. Cipődet rúgd le gyorsan; várja lágy talpadat nászi templomunk, az ágy. S le fejdíszed filigrán, csupa fény hálójával; hajad szebb diadém. Ily fehér ingben égi angyalok szállnak a földre; magaddal hozod azt, mit Mohamed Paradicsoma ígér nekünk, örök gyönyört, noha a kísértet is vászoningben jár, de főleg égnek nem a hajam áll. Engedd szabaddá szeretőd kezét, hadd nyúljon alád, mögéd és közéd. Amerikám! Frissen fölfedezett földem, melyet bejárok, fölfedek, aranybányám, országom, hol mohó kényúr vagyok, egyeduralkodó, s boldog pionír, miközben sötét kincseskamrádon ujjam a pöcsét. A lélek úgy teljes, ha testtelen, s a test akkor egész, ha meztelen. Az ékszer nem kell, az csak elvakít, mintha Atlanta kincseket hajít, s a bolond férfi szeme ottragad gyöngyön, gyémánton, mert azt látja csak, ami képkeret, könyvön díszkötés, amatőr-öröm. De ennyi kevés. Nyak, arc, derék, kar, láb, comb, csípő, mell: a szeretőnek a nő teste kell. A bűn nem bűn, és itt nem incseleg az ördög sem. Engedd le ingedet. Tárd szét magad, ne félj tőlem, ahogy There is no penance due to innocence. To teach thee, I am naked first; why than, what needst thou have more covering than a man? föléd hajlok. Gondold: bábád vagyok. Mezítelenül is gondoskodom rólad, vagy nem elég egy férfi takarónak? (Faludy György ford.) Religious poetry: the same style and method are employed; theological language abounds in his love poetry, and daringly erotic images occur in his religious verse (e.g. Holy Sonnets 18) Show me dear Christ, thy spouse so bright and clear. … Betray, kind husband, thy spouse to our sights, And let mine amorous soul court thy mild Dove, Who is most true and pleasing to thee then When she'is embrac'd and open to most men. 19 Holy Sonnets - they dramatise Donne's sense of unworthiness in contrast to divine power and mercy; 6 focus on Last Things; 6 are colloquies on divine love; 4 penitential meditations Oh my black soul! now art thou summoned By sickness, death's herald, and champion; Thou art like a pilgrim, which abroad hath done and durst not turn to whence he is fled; Or like a thief, which till death's doom be read, Wisheth himself delivered from prison, But damned and haled to execution, Wisheth that still he might be imprisoned. Yet grace, if thou repent, thou canst not lack; But who shall give thee that grace to begin? Oh make thy self with holy mourning black, And red with blushing, as thou art with sin; Or wash thee in Christ's blood, which hath this might That being red, it dyes red souls to white. (Holy Sonnets IV) Batter my heart, three-personed God, for you As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend; That I may rise, and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend Treason, Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new. I, like an usurped town, to another due, Labour to admit you, but Oh, to no end. Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend, But is captived, and proves weak or untrue. Yet dearly I love you, and would be loved fain, But am betrothed unto your enemy: Divorce me, untie or break that knot again, Take me to you, imprison me, for I, Except you enthrall me, never shall be free, Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me. (Holy Sonnets 18) the term "metaphisical" first used by Dryden; contemporaries called it "strong lines" Dr. Johnson (Life of Cowley): "about the beginning of the seventeenth century there appeared a race of writers that may be termed the metaphysical poets ... the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together" Coleridge: "the balance or reconciliation of opposite or discordant faculties" Donne's poetic fame remained high up to the Restoration; 18-19th cent.:his poetry went into eclipse (except Coleridge and Robert Browning) revival in the 20th cent. T.S.Eliot praised them highly (The Metaphysical Poets /1921/): "[The difference between Donne and Tennyson] is not a simple difference of degree between poets. It is something which has happened to the mind of England between the time of Donne... and the time of Tennyson and Browning: it is the difference between the intellectual poet and the reflective poet... A thought to Donne was an experience, it modified his sensibility. When a poet's mind is at work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience; the ordinary man's experience is chaotic, irregular; fragmentary. The latter falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these two experiences have nothing to do with each other, or with the noise of the typewriter or the smell of cooking; in the mind of the poet these experiences are always forming new wholes… In the seventeenth century a dissociation of sensibility set in, from which we have never recovered... Those who object to the artificiality of Milton and Dryden sometimes tell us to "look into our hearts and write". But that is not looking deep enough; ... Donne looked into a good deal more than the heart. One must look into the cerebral cortex, the nervous system, amid the digestive tracts." "School" of Donne: George Herbert (1593-1633); Richard Crashaw (1612-1649); Henry Vaughan (16221695); Thomas Traherne (1637-1674); Andrew Marvell (1621-1678) Andrew Marvell gathered together many strands of 17th-cent. thought: united in him a fresh, muscular and subtle metaphysical wit and the rationality, clarity, economy and structural sense of a genuine classic, the cultured, negligent grace of a cavalier and something of the religious and ethical seriousness of a Puritan Platonist. elegant, well-crafted, limpid style (cf. Ben Johnson); paradoxes, complexities of tone, dramatic monologues, witty, metaphysical arguments (cf. Donne) a number of poems published posthumously (1681) many poems explore the human condition in terms of fundamental dichotomies: The Dialogue Between Soul and Body (nature and grace, poetic creation and sacrifice) The Garden (nature and art, fallen and Edenic state, violent passion and contentment) To His Coy Mistress (flesh and spirit, physical sex and Platonic love, idealizing courtship and ravages of time) the best known carpe diem poem ("pluck the day"; a phrase from Horace: full utilisation of the present time; implicit warnings about the transience of life and inevitability of future) rapid shifts from the world of fantasy to the charnal house of reality - more than a seduction poem: a probing of existential angst Had we but World enough, and Time, This coyness, Lady, were no crime. We would sit down, and think which way To walk, and pass our long love's day. Thou by the Indian Ganges side Should'st rubies find: I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the Flood: And you should if you please refuse Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Vaster than empires, and more slow. An hundred years should go to praise Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze. Two hundred to adore each breast: But thirty thousand to the rest. An age at least to every part, And the last age should show your heart. For, Lady, you deserve this state; Nor would I love at lower rate. But at my back I always hear Time's wingèd chariot drawing near: And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast Eternity. Thy beauty shall no more be found; Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound My echoing song: then worms shall try That long preserved virginity: And your quaint honour turn to dust; And into ashes all my lust. The grave's a fine and private place, But none I think do there embrace. Now therefore, while the youthful hue Sits on thy skin by morning dew, And while thy willing soul transpires At every pore with instant fires, Now let us sport us while we may; And now, like amorous birds of prey, Rather at once our time devour, Than languish in his slow-chapt power. Let us roll all our strength, and all Our sweetness, up into one ball: And tear our pleasures with rough strife, Through the iron gates of life. Thus, though we cannot make our sun Stand still, yet we will make him run. „the predominant theme is Carpe Diem, or seize the day, an age-old theme of lyric poetry, which is appropriate for this elaborate seduction poem. The poem, however, would probably be more effective in a pagan culture than in a Christian one, where seizing the day could lead to sin and a risk of losing salvation. In fact, the Biblical references in the poem seem to be at odds with the poems apparent meaning. In this way, we could say that the poem is dialogic--that is, it presents numerous voices or discourses (in this case one representing the ethos of Carpe Diem and the other representing Christianity) to emerge and engage in dialogue. Notice, though, that these competing voices never synthesize into a coherent statement. Whereas Donne seeks always to reconcile divergent material, Marvell allows the two voices to remain dissonant.” (Christopher Johnson) famed in his day as patriot, satirist, and foe to tyranny, virtually unknown as a lyric poet high estimation of his poetry: T.S.Eliot: ’On Andrew Marvell’. „The quality which Marvell had, this modest and certainly impersonal virtue - whether we call it wit or reason, or even urbanity - we have patently failed to define. By whatever name we call it, and however we define that name, it is something precious and needed and apparently extinct; it is what should preserve the reputation of Marvell. C'etait une belle ame, comme on ne fait plus a Londres.” (for Marvell see also The New Pelican Guide to English Literature 3, ed. Boris Ford; pp.273-302)