Freshman Poetry Pkt - Jones College Prep

advertisement

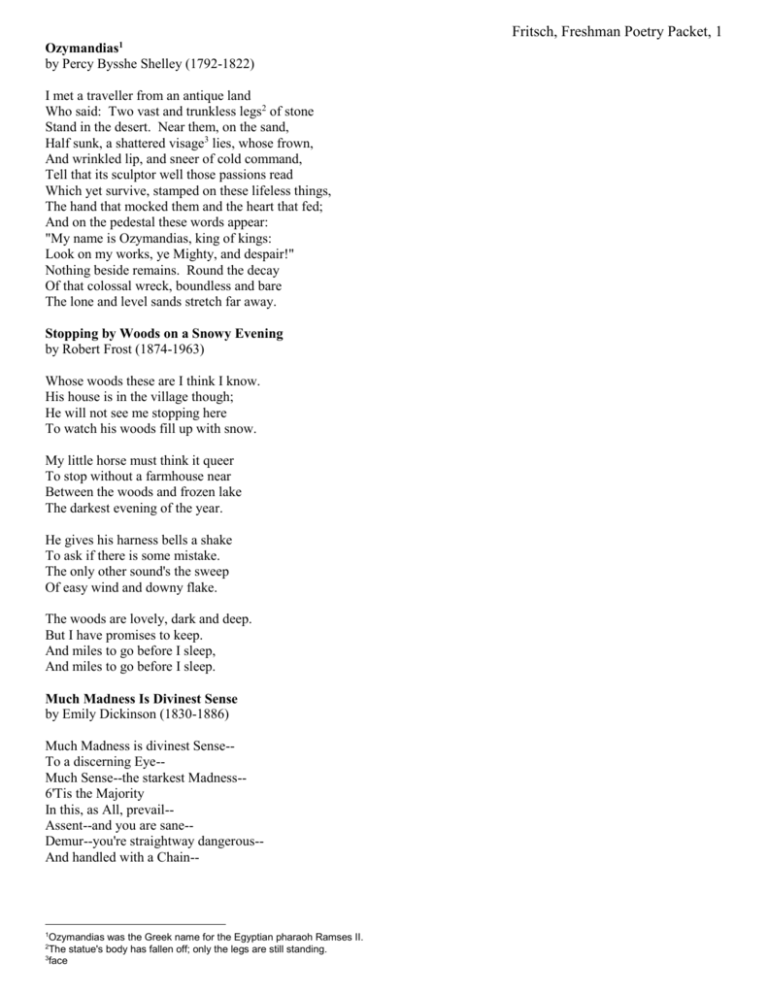

Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 1 Ozymandias1 by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) I met a traveller from an antique land Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs2 of stone Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage3 lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal these words appear: "My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!" Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away. Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost (1874-1963) Whose woods these are I think I know. His house is in the village though; He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow. My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year. He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound's the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake. The woods are lovely, dark and deep. But I have promises to keep. And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep. Much Madness Is Divinest Sense by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) Much Madness is divinest Sense-To a discerning Eye-Much Sense--the starkest Madness-6'Tis the Majority In this, as All, prevail-Assent--and you are sane-Demur--you're straightway dangerous-And handled with a Chain-- 1 Ozymandias was the Greek name for the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II. The statue's body has fallen off; only the legs are still standing. 3 face 2 Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 2 Elena By Pat Mora My Spanish isn’t good enough. I remember how I’d smile listening to my little ones, understanding every word they’d say, their jokes, their songs, their plots, Vamos a pedirle dulces a mamá. Vamos. But that was in Mexico. Now my children go to American high schools. They speak English. At night they sit around the kitchen table, laugh with one another. I stand by the stove, feel dumb, alone. I bought a book to learn English. My husband frowned, drank beer. My oldest said, "Mamá, he doesn’t want you to be smarter than he is." I’m forty, embarrassed at mispronouncing words, embarrassed at the laughter of my children, the grocer, the mailman. Sometimes I take my English book and lock myself in the bathroom, say the thick words softly, for if I stop trying, I will be deaf when my children need my help. Etymology by Amy Kashiwabara What language is that? I do not know the language my mother whispered when soldiers raided the house looking for contraband radios and children the language my grandmother shouted at a careless sea who stole my refugee aunt My older sister speaks it low over the phone the language they try to teach me It is Korean, and I can learn it. It is Korea, and I cannot. A Question of Climate by Audre Lorde (1934-1992) I learned to be honest the way I learned to swim dropped into the inevitable my father's thumbs in my hairless armpits about to give way I am trying to surface carefully Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 3 remembering the water's shadow-legged musk cannons of salt exploding my nostrils' rage and for years my powerful breast stroke was a declaration of war. The Funeral by Gordon Parks After many snows I was home again. Time had whittled down to mere hills The great mountains of my childhood. Raging rivers I once swam trickled now like gentle streams. And the wide road curving on to China or Kansas City or perhaps Calcutta. Had withered to a crooked path of dust Ending abruptly at the county burying ground. Only the giant that was my father remained the same. A hundred strong men strained beneath his coffin when they bore him to his grave. Combing by Gladys Cardiff (1942- ) Bending, I bow my head And lay my hand upon Her hair, combing, and think How women do this for Each other. My daughter's hair Curls against the comb, Wet and fragrant—orange Parings. Her face, downcast, Is quiet for one so young. I take her place. Beneath My mother' hands I feel The braids drawn up tight As a piano wire and singing. Vinegar-rinsed. Sitting Before the oven I hear The orange coils tick The early hour before school. She combed her grandmother Mathilda's hair using A comb made out of bone. Mathilda rocked her oak wood Chair, her face downcast, Intent on tearing rags In strips to braid a cotton Rug from bits of orange and brown. A simple act, Preparing hair. Something Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 4 Women do for each other, Plaiting the generations. Barbie Doll by Marge Piercy (1936- ) This girlchild was born as usual and presented dolls that did pee-pee and miniature GE stoves and irons and wee lipsticks the color of cherry candy. Then in the magic of puberty, a classmate said: You have a great big nose and fat legs. She was healthy, tested intelligent possessed strong arms and back, abundant sexual drive and manual dexterity. She went to and fro apologizing. Everyone saw a fat nose on thick legs. She was advised to play coy, exhorted to come on hearty, exercise, diet, smile and wheedle. Her good nature wore out like a fan belt. So she cut off her nose and her legs and offered them up. In the casket displayed on satin she lay with the undertaker's cosmetics painted on, a turned-up putty nose, dressed in a pink and white nightie. Doesn't she look pretty? everyone said. Consummation at last. To every woman a happy ending. The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes (1902-1967) I've known rivers: I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young. I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep. I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it. I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I've seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset. I've known rivers: Ancient, dusky rivers. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. The River Merchant's Wife: A Letter by Li-Po (702-762), trans. Ezra Pound (1885-1972) Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 5 While my hair was still cut straight across my forehead I played about the front gate, pulling flowers. You came by on bamboo stilts, playing horse. You walked about my seat, playing with blue plums And we went on living in the village of Chokan Two small people without dislike or suspicion. At fourteen I married My Lord you. I never laughed, being bashful. Lowering my head, I looked at the wall. Called to, a thousand times, I never looked back. At fifteen I stopped scowling, I desired my dust to be mingled with yours Forever and forever and forever Why should I climb the lookout? At sixteen you departed, You went into far Ku-to-yen, by the river of swirling eddies, And you have been gone five months. The monkeys make sorrowful noise overhead. You dragged your feet when you went out By the gate now, the moss is grown, the different mosses. Too deep to clear them away! The leaves fall early this autumn, in wind The paired butterflies are already yellow with August Over the grass in the West garden; They hurt me. I grow older. If you are coming down through the narrows of the river Kiang Please let me know beforehand, And I will come out to meet you As far as Cho-fu-Sa. Richard Cory by Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935) Whenever Richard Cory went down town, We people on the pavement looked at him: He was a gentleman from sole to crown, Clean favored, and imperially slim. And he was always quietly arrayed, And he was always human when he talked; But still he fluttered pulses when he said, "Good-morning," and he glittered when he walked. And he was rich—yes, richer than a king— And admirably schooled in every grace; In fine, we thought that he was everything To make us wish that we were in his place. So on we went and waited for the light, And went without the meat, and cursed the bread; And Richard Cory, one calm summer night, Went home and put a bullet through his head. Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 6 Those Winter Sundays by Robert Hayden (1913-1980) Sundays too my father got up early and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold, then with cracked hands that ached from labor in the weekday weather made banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him. I'd wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking. When the rooms were warm, he'd call, and slowly I would rise and dress, fearing the chronic angers of that house, Speaking indifferently to him, who had driven out the cold and polished my good shoes as well. What did I know, what did I know of love's austere and lonely offices4? Theme for English B by Langston Hughes The instructor said, Go home and write a page tonight. And let that page come out of you--Then, it will be true. I wonder if it's that simple? I am twenty-two, colored, born in Winston-Salem. I went to school there, then Durham, then here to this college on the hill above Harlem. I am the only colored student in my class. The steps from the hill lead down into Harlem through a park, then I cross St. Nicholas, Eighth Avenue, Seventh, and I come to the Y, the Harlem Branch Y, where I take the elevator up to my room, sit down, and write this page: It's not easy to know what is true for you or me at twenty-two, my age. But I guess I'm what I feel and see and hear, Harlem, I hear you: hear you, hear me---we two---you, me, talk on this page. (I hear New York too.) Me---who? Well, I like to eat, sleep, drink, and be in love. I like to work, read, learn, and understand life. I like a pipe for a Christmas present, or records---Bessie, bop, or Bach. I guess being colored doesn't make me NOT like the same things other folks like who are other races. So will my page be colored that I write? Being me, it will not be white. But it will be a part of you, instructor. You are white--4 daily religious ceremonies Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 7 yet a part of me, as I am a part of you. That's American. Sometimes perhaps you don't want to be a part of me. Nor do I often want to be a part of you. But we are, that's true! As I learn from you, I guess you learn from me--although you're older---and white--and somewhat more free. This is my page for English B. 1951 Because of Libraries We Can Say These Things by Naomi Shihab Nye She is holding the book close to her body, carrying it home on the cracked sidewalk, down the tangled hill. If a dog runs at her again, she will use the book as a shield. She looked hard among the long lines of books to find this one. When they start talking about money, when the day contains such long and hot places, she will go inside. An orange bed is waiting. Story without corners. She will have two families. They will eat at different hours. She is carrying a book past the fire station and the five and dime. What this town has not given her the book will provide; a sheep, a wilderness of new solutions. The book has already lived through its troubles. The book has a calm cover, a straight spine. When the step returns to itself, as the best place for sitting, and the old men up and down the street are latching their clippers, she will not be alone. She will have a book to open and open and open. Her life starts here. Saturday Afternoon, When Chores Are Done by Harryette Mullen I’ve cleaned house and the kitchen smells like pine. I can hear the kids yelling through the back screen door. Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 8 While they play tug-of-war with an old jump rope and while these blackeyed peas boil on the stove, I’m gonna sit here at the table and plait my hair. I oil my hair and brush it soft. Then, with the brush in my lap, I gather the hair in my hands, pull the strands smooth and tight, and weave three sections into a fat shiny braid that hangs straight down my back. I remember mama teaching me to plait my hair one Saturday afternoon when chores were done. My fingers were stubby and short. I could barely hold three strands at once, and my braids would fray apart no sooner than I’d finished them. Mama said, “Just takes practice, is all.” Now my hands work swiftly, doing easy what was once so hard to do. Between time on the job, keeping house, and raising two girls by myself, there’s never much time like this, for thinking and being alone. Time to gather life together before it unravels like an old jump rope and comes apart at the ends. Suddenly I notice the silence. The noisy tug-of-war has stopped. I get up to check out back, see what my girls are up to now. I look over the kitchen sink, where the sweet potato plant spreads green in the window. They sit quietly on the back porch steps, Melynda plaiting Carla's hair into a crooked braid. Older daughter, you are learning what I am learning: to gather the strands together with strong fingers to keep what we do from coming apart at the seams. After the Dinner Party by Robert Penn Warren (1905-1989) You two sit at the table late, each, now and then, Twirling a near-empty wine glass to watch the last red Liquid climb up the crystalline spin to the last moment when Centrifugality fails: with nothing now said. Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 9 What is left to say when the last logs sag and wink? The dark outside is streaked with the casual snowflake Of winter's demise, all guests long gone home, and you think Of others who never again can come to partake Of food, wine, laughter, and philosophy-Though tonight one guest has quoted a killing phrase we owe To a lost one whose grin, in eternal atrophy, Now in dark celebrates some last unworded jest none can know. Now a chair scrapes, sudden, on tiles, and one of you Moves soundless, as in hypnotic certainty, The length of table. Stands there a moment or two, Then sits, reaches out a hand, open and empty. How long it seems till a hand finds that hand there laid, While ash, still glowing, crumbles, and silence is such That the crumbling of ash is audible. Now naught's left unsaid Of the old heart-concerns, the last, tonight, which Had been of the absent children, whose bright gaze Over-arches the future's horizon, in the mist of your prayers. The last log is black, while ash beneath displays No last glow. You snuff candles. Soon the old stairs Will creak with your grave and synchronized tread as each mounts To a briefness of light, then true weight of darkness, and then That heart-dimness in which neither joy nor sorrow counts. Even so, one hands gropes out for another, again. Introduction to Poetry by Billy Collins I ask them to take a poem and hold it up to the light like a color slide or press an ear against its hive. I say drop a mouse into a poem and watch him probe his way out, or walk inside the poem’s room and feel the walls for a light switch. I want them to waterski across the surface of a poem waving at the author’s name on the shore. But all they want to do is tie the poem to a chair with rope and torture a confession out of it. They begin beating it with a hose to find out what it really means. Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 10 The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth; Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, Because it was grassy and wanted wear; Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same, And both that morning equally lay In leaves no step had trodden black. Oh, I kept the first for another day! Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back. I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference. Harlem by Langston Hughes What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode? When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer by Walt Whitman When I heard the learn’d astronomer, When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me, When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them, When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room, How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick, Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself, In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time, Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars. Fritsch, Freshman Poetry Packet, 11 A Noiseless Patient Spider by Walt Whitman A noiseless patient spider, I mark’d where on a little promontory it stood isolated, Mark’d how to explore the vacant vast surrounding, It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself, Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them. And you O my soul where you stand, Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space, Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them, Till the bridge you will need be form’d, till the ductile anchor hold, Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul. This is Just to Say by William Carlos Williams (1883-1963) I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold