The Many Deaths Of Andy Warhol

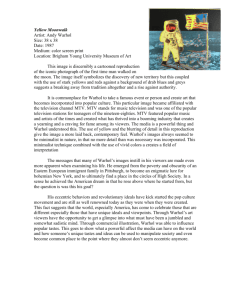

advertisement

The Many Deaths Of Andy Warhol published in Art & Australia, Spring 1987, Sydney Philip Brophy, 1987 "It's best to be born fast, because it hurts, and it's best to die fast, because it hurts, but I think if you were born and died within that minute, that would be the best life." 1 Warhol died on Sunday February 22nd 1987 at New York Hospital's Cornell Medical Centre after gallbladder surgery. A few days later, art dealer Ronald Feldman reflects on Warhol's recent works, completed (a large reworking of DaVinci's Last Supper, a set of Lenin portraits, a portfolio of prints continuing his hommage to the late Joseph Beuys) and unfinished (a commission by a Danish publishing group on Hans Christian Anderson and his fairy tales) : "Andy was on a roll this year, and he must be very angry that he died." 2 Perhaps not. A certain or particular Warhol died - that of the silver hair and black skivee ; that of whom we inscribe the 'real person' named Warhol. But other Warhols live - those that deny art ; those that speak 'the death of the artist' 3 ; those that have already died. Warhol is dead - long live Warhol. One wonders in fact if Warhol's death is an event, a point to render historic. If the Warhol we have pronounced 'artist' dies, we can romanticize his past through mourning his death, in that our mourning would be the condition of our belief in the living person as creator of art, as the one we can pronounce 'artist'. This Warhol's death would then become an event because it will cause change due to its future inability to change : the artist dies - no more art. But this romantic death is a paradox : on the one hand, the artist is para-human, above and beyond fellow humans ; on the other hand this paranormality, this genius, is extinguished in the death of the human. The paradox is covered, though, by the historicized 'life-afterdeath' of the artistic genius : the human dies - the artist lives. This of course is overly simplistic. The true values of the dead artist are mythical (created by the writings of history and criticism) and economic (determined by a state of collectability). Both values are mutually exclusive and live in a harmony peculiar to the cultural status of the artist at that point in time. It also follows that a dead Warhol does not project the same combination of values as a dead Van Gough or a dead Rothko. Or, for that matter, a dead Arthur Cravan (who?) 4 or a dead Chris Burden (is he dead?) 5 . The romanticization of the artist's death is often itself the very process used to both cite the artist's life as source of its genius and prepare the death-event for history. (In Egypt they called it mumification.) But as many counterhistories have so salaciously pointed out, most artists' life-before-death is at the other extreme to their mythical life-after-death : their twilight is the definitive Hollywood Babylon 6 where those mummies are monsters. If the monstrous is the result of mega-mythicism, Elvis (not Godzilla) is King Of The Monsters. Tales of the great hedonist hermit in his twilight mansion (part Egyptian tomb, part Baptist shrine, eerily named Gracelands) coloured his life even while he lived. Like Warhol, Elvis had died many authorial and artistic deaths before August 16th, 1977, both through offering himself up to a society for repeatable consumption and through a series of developments that signalled a draining of his consumerable energy : his conscription in 1958, the Hollywood musicals that followed, his 'live' return to Burbank (via television), Hawaii (via satellite) and Las Vegas (via film). Elvis' death - like that of the romantic paradox - was mythicised as much as his life, branded as he was with, as and by the birth of Rock'N'Roll. Warhol's portraits of Elvis are first degree eulogies, especially the more famous serialization (from 1963 onwards) of a still from Flaming Star (a telling title for all concerned). Those works celebrate not Pop music icons and their stardom (as most disposable histories of Pop would have us believe) but the nature and type of death effected by that cultural process we call fame. Art historicism has remained ignorant of the profound irony of what the Elvis series represents : a Rock'N'Roll cowboy whose hips signal death and sex ; a gunslinger, poised and ready to shoot, to give us the erotic of death ; a refugee from the Western - a cinematic genre dying a classical death by the 60s ; a superimposition of a body on a void of colour, rendered in monochrone or with garish colour-overlays, carefully illustrated or carelessly executed by the silkscreen process. Warhol - out of perversity - simply titled these works Elvis, having us assume that we were directly experiencing his picturing of Elvis, when in reality he was serializing a publicity still from a film which was a promotional vehicle for communicating the productivity of the Elvis 'phenomenon' to fuel the commodification of the Elvis 'identity'. Most Art histories have documented the simplicity without revealing its perversity. The ironies and perverisites are culturally perpetuated : in 1973 the Australian National Gallery purchased a Single Elvis from 1963 in a typical museographic gesture that celebrated the death of Pop Art as another mummy in the great halls of Modernism. The Gallery purchased the print for $25,000 at a Sotheby auction in London - by proxy, via a cable which stipulated how high they could bid 7 . Ten years later in 1983, director James Mollison would mention that Single Elvis is one of their most popular exhibits with 'the family'. One suspects that such a work most clearly communicates to 'the family' the precise function of the museum in its mummification of art, artists and all their icons. The logic flows mercilessly - true artists are dead artists ; real art depicts dead art. The Australian National Gallery's presentation of Warhol's Single Elvis gives the Elvis public everything they didn't get with the infamous shrine in the Melbourne Cemetery. And in the end (or for the time being) Single Elvis perversely does function as 'simply' Warhol's picturing of Elvis Presley. A similar functioning of fame-by-death and death-by-fame enlivens various other stars Warhol serialized in the sixties (fan magazine shots of Taylor, Monroe and Donahue, plus stills of Brando from The Wild One, Lugosi from Dracula, Cagney from Public Enemy, and Taylor from Cleopatra). In particular, the more famous Liz and Marilyn serializations evidence death in their very surfaces - do their faces not resemble the grotesque work of a mortician who lavishes over a creation of beauty to signify the end of beauty for and to the cadaver's loved ones? This effect of beauty, of marking beauty and the thin line that separates it from the monstrous, reminds us of the articulation of beauty through make-up, and of how make-up in fact signifies a lack of beauty in the same way that the beautified cadaver signifies the lack of life that generates beauty. It is further interesting to note here that the visual persona of Warhol - his image - has always been that of a cadaver, of a lack of life, of an absence of beauty. It is an image that speaks of the death that he - as creator, producer and manufacturer of absent beauty in art - both covers and imparts in his work. The greater bulk of Warhol's silkscreens from the sixties are directly concerned with death - the series and serializations of Jackie Kennedy at her husband's funeral ; suicides by jumping from building tops ; fatal car crashes 8 ; newspaper headlines of disasters ; and the infamous Ten Most Wanted Men commission for the New York World's Fair of 1964. Concurrent with the hyper-production of these works from 1962 to 1967, Warhol experimented with picturing his own image in the Self Portrait serializations, which (along with portraits of Ethel Scull, Holly Solomon, Sidney Janis and Watson Powell Sr.) prefigured what is generally referred to as his Portraits Of The Seventies 9 . Of course, the gap between 1967 and 1970 was caused by Valarie Solanis' attempted assassination of Warhol, giving the artist what would amount to a memorable death-experience. Healing from the multiple bullet wounds, Warhol said : "I don't know whether or not I'm really alive or whether I died. And having been dead once, I shouldn't feel fear. But I am afraid. I don't understand why." 10 Warhol's Portraits Of The Seventies are intensely concerned with death - not that I want to base this observation on the fraility of the above quote, but more because of the relationship he entertains with living subjects, those who willingly sit for their portraits. As has been well documented, Warhol used the Polaroid camera in the preparation for his photographic screen production because of its intrinsic capability to obliterate all but the facial contours of the subject. Warhol saw this as a 'readymade' form of beautification, cancelling out the flesh's capacity for signifying age through its texture. But consider the following : "I stand three feet away. When the flash cube goes off the people can't see a thing, so they blink. I wait 60 seconds and do another." 11 Warhol is now involved in the act of death, in capturing it in the process of portraiture and the presence of painterliness. That "flash" (an after-image of Soanis' gun blasts?) works as an erotic aroused by the state of passing into death, as a dimensional punctuation of spheres of existence. The graphic, pictorial rendering of the death act through representation (of stardom, of photography, of history, of media) in his 60s work is replaced by what in essence are snuff portraits, with Warhol as actor-murderer and cameraman-murderer. As if in a perpetual recall of both his multiple wounds (life) and his multiple absences (art), Warhol grants his subjects the experience of immortality - an experience which they can replay for themselves simply by gazing upon their death-masks, Warhol's portraits. These portraits (i) present the act of death in the event of portraiture, and (ii) represent this layering of death over life (and vice versa) by the high-contrast transparency of the photographic screenprint (the presence/absence of the subject) overlaying the opaque, painterly terrain underneath (the presence/absence of the artist). Moreover, this layering is blurred and blended by a clash of surfaces, creating the illusion of each lying within one another. In a way, this textual trompe l'oeil replicates the strange simultaneity of birth and death that Warhol talks of in the initial quote above, that which he describes as "the best life". It appears to be a time where one is not even aware of the difference between life and death - a difference whose lack and gain are displayed, demarcated and dissolved in virtually all of Warhol's work in one way or another. A great part of the Warhol myth deals with his removal, his absence, his negation of material and mechanical involvement with the production of his work, usually circulated around his infamous denial of humanism : "I want to be a machine". However, it could be more likely that these various absences and absentings propel the desire of death through a carthartic release in the act of being absent. In 1967 (the year of his 'brush with death') Warhol hired Allen Midgette to impersonate Warhol on a college lecture tour - where Midgette had to perform the typical Warhol by not answering questions and letting other 'super stars' like Gerard Malanga field the questions. In 1969 (almost as a warm-up event for the Portraits Of The Seventies) Warhol posed for Richard Avedon, the result being that portrait of Warhol baring his scared torso, providing photographic proof of his life-after-death. Sometime in the early seventies, Warhol - as part of his retirement from painting exhibited some of his 'super stars' (among them : Brigid Polk, Gerard Malanga and Candy Darling) in person, having them tied by a lease to the gallery wall. After being exhibited, they were available to be rented from $4000 to $5000 a week : "People only want art so they can talk about it. This way they can take the art home, have a party for it, show it to their friends, take Polaroids of it (which I will sign), make tape recordings. And after the week is over, they'll still have anecdotes." 12 No doubt the process of portraiture was more economical and more sellable, but still one can see links between the Portraits and the 'people art' - the objectification of the body ; the commodification of the act of possession ; the replaying of the experience ; etc.. Warhol's self-declared retirement from painting was most likely a pause wherein he came to terms with how he should deal with death in art and the death of art now that he himself was living a life-after death. On the economic plane, the artist Warhol (the person to whom we attrribute the culutrual origination of value) died in an everyday ocurrence in capitalist society : incorporation. Surely this must be the greatest fear of the romantic ethos of art and artists - replacing the artist's decisions (the proof of his life force) by hegemonic manoeuvres determined by monetary growth. Warhol's first fundamental death in this direction was neither his repetition of pre-designed graphics (soup labels, stamps, adhesive labels, dollar bills, drink bottles, dance diagrams) nor his selection of the silkscreen process - but the stamp he ordered made to function as his signature. By this decision and process, Warhol inverted Duchamp's gestural signing of the toilet basin (as "Mr. R. Mutt") and transformed the gesture into a manoeuvre : he replaced the alter-ego with a logo. Warhol incorporated himself through a series of moves which followed the pattern of his cultural exchanges : from the production of the Velvet Underground's first album to the promotion of The Erupting (later Exploding) Plastic Inevitable tours to Morrisey's early films to the publishing of Interview magazine to the franchising of his name for the Andymat fast food restaurants 13 to the executive production of the Andy Warhol's TV cable show to the guiding of the ever-present Factory. In legal terms, the act of incorporation is not only the forming of a buisness body, but also the disappearing of the human body, of the person(s) to whom decisions can be singularly traced. Warhol's life as a true Pop artist has always been assured and insured through his death by incorporation. In summation, Warhol's artistic life can be divided into two death phases, separated by Solanis' gun blasts : (i) death by painting, by the signification of his artistic and authorial absence, and (ii) death by the painter, by the materialization of his artistic and authorial presence. In this sense, the screen-prints from 1962 to 1967 are deathly ; those from 1967 to 1987 are ghostly. Not only the Portraits, but also series like Myths, Skulls, Shadows and Endangered Species, and especially the Reversal Series, where all his now-incorporated icons from the sixties are rendered as apparitions in negative. (All these latter works await further analysis along such lines.) This article is too brief to fully discern, analyze and propose all that has yet to (and should already have been) written about Warhol outside of the banal voices of certain art histories' obsession with formalism and imperception of mass media. As suggested by his death, I have picked on one of many possible thematic effects which run through Warhol's work - that of the notion, act, event and dimension of death - and to introduce it as such. Most importantly, it is in death that we find an integral link with Duchamp through a shared dandyism : Duchamp spoke of the death of Art ; Warhol speaks of how Art is death. NOTES 1 Taken from an issue of the drug culture magazine HIGH TIMES from around 1979, in which Warhol wrote a celebrity one-off column about his then-chosen favourite topic, fast life, titled Why I Love To Live Fast. 2 As reported by Grace Glueck in THE NEW YORK TIMES Arts & Entertainment section on Thursday February 26th, 1987. (TEXT MISSING HERE FROM FILE CORRUPTION - awaiting data re-entry) ... Barthes' article titled The Death Of The Author, which clearly and simply lays some fundamental groundwork in how one can begin to discern the multiple modalities, layers, acts, performances and events of writing within a given text in relation to our conceptualization of its author. (The article itself is not as important as the general area of linguistic discourse and its relation to cultural production.) More specifically, I relate this notion of death to Warhol following Robbe-Grillet's comments on Lichtenstein as reprinted in Roy Lichtenstein, edited by John Coplans (Praeger Publishers Inc. 1972). 4 Arthur Cravan : boxer, poet, sailor, Dadaist. He apparently disappeared one day in 1918 sailing in an absurdly small boat in the Gulf of Mexico to meet his wife as part of what was presumed to be his ultimate Dada gesture. 5 No - but what would the market value of Burden's body be if those bullets did kill him, or if those cars on the L.A. Freeway had killed him? 6 The title of Kenneth Anger's volumes which detail the underside of Hollywood's many and varied tragic deaths. 7 As reported by Ken Davis in the Melbourne SUN, July 7th 1973. 8 I shall never forget as a teenager being chided by an adult for admiring Warhol's Saturday Disaster series because of my ignorance of the fact that Warhol would get ambulance drivers to phone him up to rendezvous at the scene of a horror smash where the drivers would wait around for Warhol to snap his pics while innocent people died. An extreme and hysterical example of the confusion of image with reality. 9 The title of the Whitney Museum exhibition of Warhol portraits in 1979. The Random House book serves as the show's catalogue. In many articles, the Mao serialization of 1972 is cited as the first '70s portrait' (coinciding with his publicized 'return to painting') although portraits like that of Dennis Hopper and some of the later Self Portraits appear to cover the 1969-1970 period. One should also note the commissions for album covers (The Rolling Stones, Dion, Diana Ross, Julien Lennon and Aretha Franklin) and book jackets (James Dean and The Beatles) Warhol recieved throughout the seventies and into the eighties. 10 Quoted in Carter Ratcliff's Warhol (Abbeville Modern Masters series, 1983) from Peter Gidal's Andy Warhol, Films & Paintings. 11 As quoted by Kathleen Brady in THE AUSTRALIAN WOMEN'S WEEKLY, January 25th 1978. 12 As quoted in an obscure article (torn from a second-hand magazine and passed onto me) on 'contemporary art' from what could be ESQUIRE from around 1970. 13 As reported by 'Dick Tracy' in THE NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS sometime in Summer, 1978. The article cites Araldo Cossuta as the restaurant's architect and quotes a spokesman saying that the Andymat's aim is "to recapture the gracious format of a varied menu served in comfortable surroundings". The Andymat (due to have opened in Autumn 78 - did it actually open?) serves 75 different dishes of frozen food.