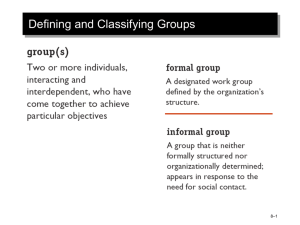

Foundation of Group Behavior Ch. 6

advertisement