Urban Agriculture and Oakland

advertisement

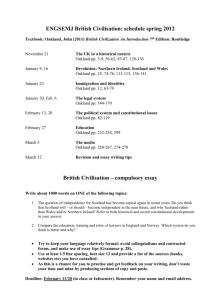

Urban Agriculture and Oakland Christina Parker Christina Parker ENVS 450 Fieldman DUE 29 November 2011 INTRO Policies designed to enhance backyard and community farm-gardens would be a helpful boost for small-scale food production within the city of Oakland. This boost is necessary to alleviate issues of disparate access to healthy food because of poverty, the presence of food deserts, and diet related illnesses that are characteristic of Oakland. This paper seeks to examine the physical obstacles to urban agriculture in Oakland, as well as city level policy and planning paradigms and specific laws, which obstruct the City of Oakland’s ability to create a larger urban agriculture movement, to mitigate the negative effect of food related issues. First, I will first examine the specific challenges that Oakland faces in relation to food. These have been identified as disparate access to food related to poverty, the presence of food deserts, and the occurrence of diet related illnesses. I will determine whether these issues can be addressed through urban agriculture. This involves a critical literature review of peer-reviewed articles on urban agriculture, as they pertain to Oakland’s specific attributes. Urban agriculture has been implemented in many cities for many decades with mixed results from which we can learn and draw conclusions. This review portion of the research project also offers an opportunity to ask the logical background question, which must be answered before we begin to analyze obstacles to urban agriculture in Oakland. This question is: is urban agriculture is worth fighting for (i.e. will it substantially mitigate the food related issues residents of Oakland experience related to hunger, food deserts, and diet related health issues?) Once we have determined that urban agriculture does have something to offer Oakland, we then must answer the question of why it is so hard to implement. OAKLAND’S ATTRIBUTES POVERTY In Oakland, economic hardship is a reality for many residents. Overall, seventeen percent of Oaklanders live in poverty as compared with thirteen percent of Americans in general. (Oakland Local) The numbers become even more drastic as we look at specific communities. Twenty five percent of Oakland’s children live in poverty, as do twenty five percent of East Oakland residents. (http://www.healthycal.org/archives/2216) This means that many Oaklanders cannot afford the bounty of the local Whole Foods Market, or the nearby Berkeley Bowl, where food is healthy and expensive. In fact, a “UCLA Center for Health Policy Research study published in 2005 concludes that about 33 percent of Bay Area residents are ‘food insecure,’ meaning they cannot afford healthy food.” (New Food Policy Council) FOOD DESERTS To further exacerbate Oakland’s poverty, is the issue of food deserts. In West Oakland, for example, there is not a single grocery store, and since “nearly half of residents (of West Oakland) rely on public transit,” finding time to buy food from a store in a nearby neighborhood can be an impossible task for a single mother or busy working family. (Woodall) When asked, residents say they would prefer “a variety of several smaller stores scattered around the spreadout district.” (Woodall) Instead, West Oakland has liquor stores and corner markets. These locations offer processed and packaged food with little in the way of fresh produce or healthy choices. Furthermore, prices at corner and liquor stores are often “100 percent more” than supermarket prices. (Ramanujan) DIET RELATED ILLNESS Because of a combination of an inability to afford healthy food, and an inability to access healthy food, Oakland residents are dealing with food related health issues in alarming numbers. In West Oakland, where there is no grocery store, heart disease is the leading cause of death, and type two diabetes hospitalization rates are twice as high as the Alameda County average. (County Health Status Report, 2000) UA’s MITIGATING EFFECT ON OAKLAND’S FOOD RELATED ISSUES Urban agriculture “can include community and private gardens, edible landscaping, fruit trees, food-producing green roofs, aquaculture, farmers markets, small-scale farming, hobby beekeeping, and food composting”, which takes places in a city, for the benefit of residents of that city. (Mendez) This is not a new concept; urban agriculture is a tested method that “has a positive impact on the household food security and nutritional status of low-income groups in cities,” because food is grown and consumed within the community. (Maxwell) Urban agriculture can soften the blow felt by many families in times of economic recession thus “playing an…important role in protecting the poorest urban dwellers as they cope with an economic crisis”. (Zezza) As our economy experiences economic turmoil, the poor often suffer the most. Communities like West Oakland where “20-30% of the population lives below the poverty line” stand to benefit from the benefits of UA. By producing food locally we reduce the need for costly transportation, the involvement of ‘middle men’ like distributers and stores, which mark up prices, and, notably, we allow for food to be accessible in places where there are still no stores. Furthermore, local food production can foster community involvement, which may give the residents of Oakland a chance to organize around food related issues. (Community Health Status Report) One study which sought to understand the sociological benefits of urban agriculture found that “time spent in a community garden was a stronger…predictor of political citizenship orientations than was time spent talking and visiting with other community gardeners, which implied the significance of the garden space and its public sphere effects.” (Glover) In this way urban agriculture goes beyond alleviating poverty, and begins to open the door for civic participation which can further address the roots of food related issues like the presence of food deserts. It is logical that people who grow their own vegetables will be provided with healthier, fresher options than processed, packaged, or otherwise treated foods from stores, and that this can help reduce diet related illnesses. This idea was expanded on by a 1998 study by the International Food Policy Research Institute, which found that “urban agriculture has a positive, significant association with higher nutritional status of children…and is associated with improved quantity and quality of food consumption and with increased time for child …[which] is negatively associated with the occurrence of illness.” (Maxwell) The study concluded that, “urban agriculture is clearly a successful strategy in buffering the impact of economic hardship on nutritional status.” (Maxwell) OAKLAND’S OBSTACLES With proven benefits and local support, it can be hard to identify Oakland’s major obstacles to promoting urban agriculture on a citywide level. However, those who have gone through the process of trying to start a community garden on their own, or on city property, know all too well that the present system in Oakland is not always amenable to the urban gardener. First, we will address the spatial obstacle by determining whether there is adequate space for urban agriculture, this involves a review of the policy obstacles to utilizing available space for this purpose. Then we will examine the priorities, or the dominant paradigm, which governs the policy decisions that impact urban agriculture. PHYSICAL OBSTACLES For now, let us be content with the fact that soil contamination can be dealt with either by remediating the soil (i.e. planting plants which will absorb heavy metals and pollutants from the soil before planting crops for consumption) or by planting in raised beds. We can then infer that the main physical factor limiting how much farming can take place in a given city is space. Cities like Detroit have thousands of acres of abandoned or unused property, which is ideal for urban agriculture. Despite what one might deduce from a quick look around West Oakland, however, Oakland is not as inundated with unused spaces. Property values are high in the Bay Area, and thus unused land can be hard to come by. This is not to say that urban agriculture cannot take place in Oakland, but rather that the approach needs to be carefully calculated. Nathan McClintock & Jenny Cooper, students with the Department of Geography at UC Berkeley, have conducted a report entitled “Cultivating the Commons: an Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland’s Public Land”, which seeks to determine how much space is available for urban agriculture in the City of Oakland, using GIS technology. The study identified “1,201 acres of [publicly owned] open space (not including land with dense vegetation)” that would be ideal for urban agriculture. (McClintock) The identified land is ideal in that it is predominantly close to public transit lines, owned predominantly by the Oakland office of Parks and Recreation, (but does not include developed park land such as soccer fields or basketball courts), and is predominantly located in East and West Oakland, the very places where fresh fruits and vegetables are needed most. The study concludes that there is room for urban agriculture in Oakland, but that private property, including vacant lots, rooftops, and private yards should also be included in any effort to implement an urban agriculture program in Oakland in order to optimize the percentage of Oakland’s food demand that can be satisfied. The study found that privately owned vacant lots alone totaled 864 acres of potential farming land, and could be used to cultivate up to ten percent of the cities fruit and vegetable needs, while existing public spaces could be used to cultivate an additional five percent of Oakland’s vegetable needs, and six percent of fruit needs. (McClintock) POLICY OBSTACLES While it may seem that the question of how much space is available for urban agriculture is not directly related to policy, this is not the case. There are two main ways in which policy could optimize available space for gardening (other policies which may also increase the amount of space available by including spaces not mapped by the Cultivating the Commons report will be discusses in the subsequent paragraph on the planning paradigm). First, as ‘Cultivating the Commons’ suggests, education programs, which seek to create farmers who posses the tools and knowledge necessary to grow crops efficiently could double the productivity of available space for gardening. (McClintock) This conclusion was expounded on by a report from the Oakland Mayor’s Office of Sustainability, entitled “A Food Systems Assessment for Oakland: Toward a Sustainable Food Plan” which states that “according to…sustainable mini-farming methods, a skilled farmer can produce 2 to 6 times the yield compared to commercial agriculture, while using 67%-88% less water, 99% less energy and 50%-100% less purchased organic fertilizer per unit of yield compared with commercial agriculture.” (Unger, 2004) This report highlights the importance of educating people about how to farm efficiently by pointing out that an educated, efficient farmer can not only out produce an unskilled counterpart, but can actually produce more food per foot, using less resources than a commercial operation. Maximizing the yield of each garden plot through gardener education should be a main policy focus of urban agriculture programs in Oakland, due to the limited space available for farming. The second way to incentivize the opening and utilization of more spaces for urban agriculture is by making farming an economically feasible activity. Right now, permitting is a major policy barrier to the feasibility of urban agriculture. Oakland residents currently need a Conditional Use Permit in order to sell home grown produce in Oakland, the cost of which is over two thousand dollars. One third of the Bay Area is food insecure, and these people may not have thousands of dollars with which to buy permission to sell chard to neighbors. Furthermore, the Conditional Use Permit is necessary even for those who sell their vegetables by donation. (Hautala) This issue was brought to light by the struggles of Novella Carpenter, a beloved Oaklander who has a garden on a lot in West Oakland. Novella came into the spotlight when the city singled out her farm and fined her thousands of dollars for failure to posses a Conditional Use Permit while accepting donations for chard. (Hautala) The community responded with outrage at the very idea of charging someone thousands of dollars for offering chard in exchange for donations, especially in a community plagued by the food related issues we have discussed; poverty and hunger, food deserts, and diet related illnesses. The City of Oakland is now considering revising this policy, but residents must maintain pressure on city officials if this struggle is to be seen through to the end. Furthermore, the city must consider that even if they reduce the cost of a conditional use permit to a few hundred dollars, as has been proposed, many of the most economically challenged residents of Oakland will not be able to afford this, and will thus write off urban agriculture as too expensive. This is very damaging to the movement because economically challenged residents are the very people to whom urban agriculture can bring the most benefits. DOMINANT PARADIGM We have seen that much of the land which could potentially be used for UA is owned by the City of Oakland, and we have seen that one third of residents of the City of Oakland are food insecure. (McClintock) This draws attention to the fact that resident’s needs are not being met by the dominant paradigm, or set of priorities, which governs decision making within the City of Oakland. The City of Oakland, as well as land-owners who own vacant properties, are reluctant to make space available for community needs such as UA, because they are focused on the potential for “more lucrative [land] uses [which may be proposed by] other investors later on.”(Choo, 2011) This highlights a fundamental issue, says Catherine LaCroix, a land-use law professor at Case Western Reserve University School of Law, because “the whole system is set to lead to profitable development.” This comment highlights the need for a new definition of what constitutes profitable development. The profits seen from expensive ‘live work lofts’ and large shopping centers go back into the pockets of land owners and the City, which continues to develop in ways which push poor residents out of our communities. Instead we could use the available space to create a more prosperous and healthy life for the people who already live in a given city. By talking about shifting our focus, from profits for landowners to prosperity for residents, we are discussing a paradigm shift. One example of the City serving the needs of developers and corporations over residents is the use of eminent domain to build a Food Co in West Oakland, the community which, when polled, asked for small stores around the large neighborhood. To address the fact that West Oakland has gone fifteen years without a grocery store, the City of Oakland has elected to employ eminent domain in order to forcibly purchase land in West Oakland, which will be used by the Kroger Corporation to build a Food Co. However, this may not be the golden ticket out of food issues that Oakland city officials hope. Many residents of Oakland are worried that “processed, sugary, high fat items Foods Co infamously stocks lower (will) ultimately raise the incidence of diet-related diseases among underserved communities.” (Holt-Gimenez, 2010) Furthermore, the community worries that the Kroger Corporation, which will be building the Food Co., has profits, rather than community, as its core value. Residents fear that jobs at Food Co. are likely to be low paying, and that if the company does not wind up making enough of a profit, they are liable to leave the community high and dry again. Furthermore, even if Kroger does end up making a profit, the City of Oakland will not be reaping the benefits, since “corporate operations…send most of the purchasing power out of town.” (Holt-Gimenez, 2010) Through community discussion of the inadequacies surrounding Kroger Co as a solution to food issues, Oaklanders have touched upon something deep. The community realizes that the dominant paradigm, (defined as the “set of assumptions, concepts, values, and practices that constitutes a way of viewing reality”), is the real problem in West Oakland, not just the lack of a grocery store. (Paradigm - Definition of Paradigm by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia) SIGNIFICANCE Poverty and food deserts combine to create a problem of disparate access to healthy foods which is not unique to Oakland. In a world where “more than half of the population is urbanized” and urbanization is rapidly increasing, we need to find strategies which help bring food to the urban poor, and urban agriculture is one strategy that has been “closely related to food security.” (Sonnino, Zezza) “Rural-to-urban migration over the latter half of the twentieth century, has led to a loss of farmland near urban areas”, which has in turn led to a hunger problem amongst the poor in cities that surpasses the hunger issues dealt with by the poor in rural areas. (Sonnino) This is because the rural poor remain close to sources of food production, and more often have access to land for farming, and therefore experience higher food security, whereas “in cities, lack of money translates more directly into lack of food.” (Sonnino) Worldwide, cities have been taking note of the growing need for urban areas to be more directly linked to food production for a multitude of reasons. Urban agriculture “minimizes the ecological impacts of food production… contributes to individual and communal health…responds to the differing food and nutritious needs of… diverse populations, and ensures a more regular supply of food for urbanities that are normally neglected by long-distance food chains.” (Sonnino) Fast growing cities like Beijing, and developing communities in Africa are already incorporating urban agriculture programs into their city plans. (Sonnino) Urban Agriculture can change our communities and mitigate the effects of poverty, food deserts, and diet related illness, as well as reaping subsequent benefits such as “teaching residents about health, nutrition, and ecology; offering neighborhood green space for recreation, conservation, and beautification; improving public safety by connecting neighbors, rejuvenating underutilized spaces, adding "eyes on the street"; and creating economic opportunity through green jobs.” (Urban Agriculture - Oakland Food Policy Council) Works Cited 1. Choo, Kristin. "Plowing Over: Can Urban Farming Save Detroit and Other Declining Cities? Will the Law Allow It? - Magazine - ABA Journal." ABA Journal - Law News Now. Justica, Aug. 2011. Web. 28 Nov. 2011. <http://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/plowing_over_can_urban_farming_save_detroit_a nd_other_declining_cities_will/>.Works Cited 2. County Health Status Report 2000. Alameda County Public Health Department Community Assessment, Planning and Education Unit. July, 2000 (http://www.co.alameda.ca.us/publichealth) 3. Glover, T., Shinew, K., & Parry, D. (2005). Association, Sociability, and Civic Culture: The Democratic Effect of Community Gardening. Leisure Sciences, 27(1), 75-92. doi:10.1080/01490400590886060. 4. Hautala, Laura. Do You Need a Permit to Grow Swiss Chard in Oakland? Baycitizen.org, 31 Mar. 2011. Web. 15 Nov. 2011. <http://www.baycitizen.org/food/story/iconic-urban-farmernovella-carpenter/>. 5.Holt-Gimenez, Eric. "King of the Food Deserts | Common Dreams." Home | Common Dreams. Common Dreams, 15 Oct. 2010. Web. 03 Nov. 2011. <http://www.commondreams.org/view/2010/10/15-3>. 6. Maxwell, D., Levin, C., & Ceste, J. (1998). Does urban agriculture help prevent malnutrition? Evidence from Kam. Food Policy, 23(5). Retrieved November 30, 2010, from www.sciencedirect.com.opac.sfsu.edu/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VCB-3VS2K477&_user=521824&_origUdi=B6VC6-3YCMM4R11&_fmt=high&_coverDate=10%2F31%2F1998&_rdoc=1&_orig=article&_origin=article&_zo ne=related_art&_acct=C000059577&_version=1&_urlVer 7. McClintock, Nathan, and Jenny Cooper. Cultivating the Commons:An Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland’s Public Land. Rep. HOPE Collaborative, Oct. 2009. Web. 10 Nov. 2011. <http://www.oaklandfood.org/media/AA/AD/oaklandfoodorg/downloads/27621/Cultivating_the_Commons_COMPLETE.pdf>. 8. Mendes, W., Balmer, K., Kaethler, T., & Rhoads, A. (2008). Using Land Inventories to Plan for Urban Agriculture: Experiences From Portland and Vancouver. Journal of the American Planning Association, 74(4), 435-449. doi:10.1080/01944360802354923. 9. "New Oakland Food Policy Council Sets Course for Better Food Access, Social Change | Oakland Local." Oakland Local | News & Community Voices. Oakland Local, 09 Oct. 2009. Web. 28 Nov. 2011. <http://oaklandlocal.com/article/new-oakland-food-policy-council-setscourse-better-food-access-social-change>. 10. "Paradigm - Definition of Paradigm by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia." Dictionary, Encyclopedia and Thesaurus - The Free Dictionary. Farlex. Web. 15 Nov. 2011. <http://www.thefreedictionary.com/paradigm>. 11. Ramanujan, K. (n.d.). Urban Farmers Provide Nourishment in Low-Income Neighborhoods. Just Garcia Hill: A virtual community for minorities in sciences. Retrieved November 30, 2010, from http://justgarciahill.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=296&Itemid= 12. "The Numbers: Oakland Has a Greater Percentage of College Graduates, People Living in Poverty than the Nation | Oakland Local." Oakland Local | News & Community Voices. Oakland Local, 04 Jan. 2011. Web. 28 Nov. 2011. <http://oaklandlocal.com/article/numbers-oakland-hasgreater-percentage-college-graduates-people-living-poverty-nation>. 13. Unger, Serena, and Heather Wooten. A FOOD SYSTEMS ASSESSMENT FOR OAKLAND, CA: TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE FOOD PLAN. Rep. Oakland Mayor's Office of Sustainability, 24 May 2006. Web. 10 Nov. 2011. <http://oaklandfoodsystem.pbworks.com/f/Oakland%20FSA_6.13.pdf>. 14. Woodall, A. (2010, October 4). Neighbors divided over West Oakland grocery plan ContraCostaTimes.com. Home - ContraCostaTimes.com. Retrieved November 30, 2010, from http://www.contracostatimes.com/news/ci_16233076?nclick_check=1 15. Witt, S. (2001). West Oakland Community Information Book. Oakland: Alameda County Health Care Services Agency. 16. Zezza, A., & Tasciotti, L. (2010). Urban agriculture, poverty, and food security: Empirical evidence from a sample of developing countries. Food Policy, 35(4), 265-273. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.04.007.