36k doc - UCLA.edu

advertisement

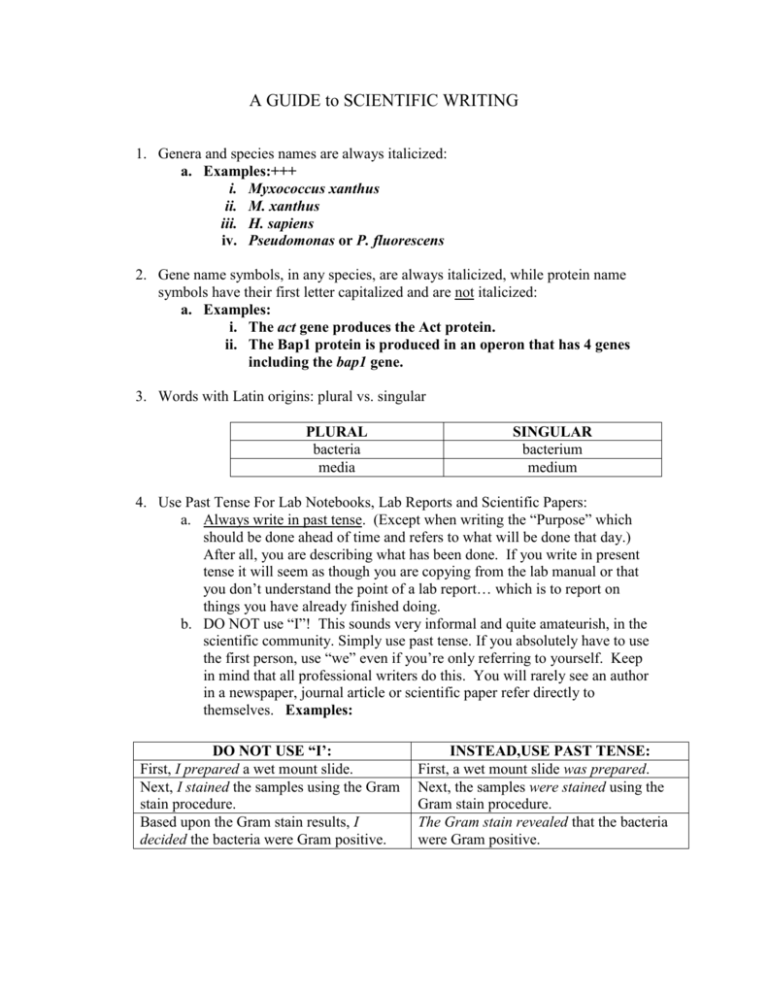

A GUIDE to SCIENTIFIC WRITING 1. Genera and species names are always italicized: a. Examples:+++ i. Myxococcus xanthus ii. M. xanthus iii. H. sapiens iv. Pseudomonas or P. fluorescens 2. Gene name symbols, in any species, are always italicized, while protein name symbols have their first letter capitalized and are not italicized: a. Examples: i. The act gene produces the Act protein. ii. The Bap1 protein is produced in an operon that has 4 genes including the bap1 gene. 3. Words with Latin origins: plural vs. singular PLURAL bacteria media SINGULAR bacterium medium 4. Use Past Tense For Lab Notebooks, Lab Reports and Scientific Papers: a. Always write in past tense. (Except when writing the “Purpose” which should be done ahead of time and refers to what will be done that day.) After all, you are describing what has been done. If you write in present tense it will seem as though you are copying from the lab manual or that you don’t understand the point of a lab report… which is to report on things you have already finished doing. b. DO NOT use “I”! This sounds very informal and quite amateurish, in the scientific community. Simply use past tense. If you absolutely have to use the first person, use “we” even if you’re only referring to yourself. Keep in mind that all professional writers do this. You will rarely see an author in a newspaper, journal article or scientific paper refer directly to themselves. Examples: DO NOT USE “I’: First, I prepared a wet mount slide. Next, I stained the samples using the Gram stain procedure. Based upon the Gram stain results, I decided the bacteria were Gram positive. INSTEAD,USE PAST TENSE: First, a wet mount slide was prepared. Next, the samples were stained using the Gram stain procedure. The Gram stain revealed that the bacteria were Gram positive. c. Exception: you can use future tense when discussing future plans or experiments in the discussion section of your paper. It is often in the discussion section of the paper where you can refer to yourself as “we.” Again, even though the discussion section is a little more informal, do not use “I”. i. Examples: 1. In future experiments, the bacteria will be isolated and identified. 2. In future experiments, we plan to isolate and identify soil bacteria from the genera Pseudomonas. 5. DO NOT use contractions. Contractions are not acceptable in any type of formal writing and they are not accepted in scientific writing. a. DO NOT use “can’t” or “it’s” b. Instead use “cannot” or “it is,” etc. 6. Figures, tables, charts: a. Charts, tables (etc.) are a good way to strengthen your argument and show that you have synthesized/summarized important information or concepts. Do this whenever possible. It also demonstrates good organization and clear thinking. b. Label all tables, charts, figures (etc.) and capitalize the name of it. For example: “Figure 1.” or “Table 2.” c. If you include any figure, table, chart, picture, diagram, (in a paper or report write-up) you must label it, and refer to it in your writing. Explain why this chart is there and what it is supposed to show or explain. DO NOT include any charts, figures (etc.) if you are not going to refer to it. Failing to refer to the chart makes a paper or report seem unpolished and a little thoughtless. i. Example: 1. “All results obtained from the experiment are summarized in Chart 1.” 2. Or, you could write, “We conducted ten distinct biochemical tests and recorded the results the following day (Chart 1).” 7. Vocabulary: a. Pretend you’re a lawyer or a private investigator solving a crime. It can be helpful to think of the scientific process as very similar to trying a case in court. Your lab reports or scientific papers can use the same type of language (i.e. “legaleeze”) to describe what you have done in your experiments and the conclusions you have drawn. i. Examples 1. Based on the tests performed, the evidence strongly suggests that our sample is Myxococcus xanthus. 2. By the process of elimination, possibilities x, y, and z were ruled out. 3. The evidence points to candidate X as the probable identity of the unknown. b. Use formal vocabulary. Do not use slang or casual language. Remember, this is a formal document that reflects on your thinking processes and intellectual ability. With this in mind, you should pay attention to your vocabulary. If something sounds too casual, look for another word or phrase in an online thesaurus. Here are some examples: INSTEAD OF: I put the slide on the microscope I did the following experiments. After looking at the data, I think my sample is X. USE THIS: The slide was placed on the microscope. The following experiments were performed. Or…The following experiments were carried out. After analyzing the data, we conclude that the sample is X. 8. DO NOT Make Absolute Statements.: a. Learning to phrase your conclusions without resorting to absolute statements is another convention of formal scientific writing. When you are answering questions in a lab notebook or writing conclusions in a report, you may think the professor/TA wants you to be 100% right or to figure out the absolute truth of the matter. However, that is not the case; they want you to draw a well-reasoned conclusion based on the evidence (your results). Every scientist, lawyer, or investigator knows they are not going to be correct every time. The important thing is to make the best conclusion you can and cite your reasons, evidence, data, etc. Therefore, this uncertainty should be reflected, very subtly, in your writing. If you do this, your writing shows that you know what is expected of you as a scientist (you are expected to collect and analyze data, and then to draw appropriate conclusions –not to assume you have found the ultimate truth) and your writing will have a more sophisticated tone. But if you resort to making absolute statements, not only will your writing seem amateurish, but you will often make statements that are completely false. i. Examples 1. Do not say, “There is no doubt that our bacterium is Pseudomonas aeruginosa.” 2. Instead say, “Our results provide strong evidence that our sample is Pseudomonas aeruginosa.” 3. Or use “likelihood.” “Based on the results described in Table 2, our sample is most likely Pseudomonas aeruginosa.” 4. Or, present your conclusion as the best choice out of the possible choices. “Table 3 illustrates the results of our experiments compared to all the possible outcomes. After comparing our results to the outcomes for sample B, it is evident that sample B is the best match. MORE VOCABULARY AND PHRASES Experiment, study, examination, test Illustrate, indicate, demonstrate, show, point to Conclude, determine, identify, discover, find, reveal, uncover, solve, resolve, verify (Conduct, perform, carry out) an experiment data, evidence, results, outcomes, findings candidates, possibilities distinguish, differentiate