We the future: Teaching students about presidential elections.

advertisement

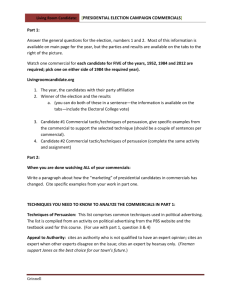

The Georgia Social Studies Journal Fall 2012, Volume 2, Number 2, pp. 38-45. Georgia Council for the Social Studies We the future: Teaching students about presidential elections. Jeremiah C. Clabough The University of Alabama at Birmingham Thomas N. Turner The University of Tennessee Gary W. Cole Sequoyah High School (Madisonville, TN) This article explores four approaches and multiple activities for teaching about presidential elections. The activities presented focus on getting to know the candidates, knowing and understanding the issues important to the election itself, learning about the stance of each candidate on the issues, and understanding the national election process for the presidential election. The activities included in this article are: Charting the Desirable Traits of the President, Learning about the Electoral College, Getting to Know Each of the Candidates, “Pants on Fire” Awards for candidates who make inaccurate statements; and Presidential Speed Dating, a center-based look at how individual candidates stand on the issues. Each of the activities is described with attention paid to how teachers can implement them in the classroom. If we fail at preparing students to be good citizens, schooling itself breaks down. It has no value, no purpose, and no use—for the society itself cannot survive. In Defining the Social Studies, one of the most often cited books in social studies education, Barr, Barth, and Shermis (1977) contended that the central purpose of the social studies is citizenship education. Teaching our children to be good citizens is the quintessential mission of school and of the social studies. If they grow up to be geniuses in the arts, science, and math, without the passionate, concerned, responsible caring of good citizens, schools have totally failed and we have left all children behind. Being a good citizen in American society does not mean thinking exactly like the President, always agreeing with the laws Congress passes, or the decisions of the Federal Courts. What it does mean is thinking for oneself, participating as an informed voter in elections, and knowing when and how to protest or to support the government in legal responsible ways. Kahne and Middaugh (2006) have pointed to two types of problematic citizens. In particular, they caution against passive and blind patriots. The former are inactive and unengaged as citizens. The latter are blindly committed to unreasoning support of the existing government. For the vitality of a democracy, it is important to have healthy discussions on political issues with different perspectives (Hess & Ganzler, 2007). According to the Citizenship Education Foundation (2012), citizenship education is about enabling people to make their own decisions and to take responsibility for their own lives and their communities. Nowhere are we reminded more of this than that period every four years when we prepare for presidential elections. At this time, we are dealing with what Ben-Porath (2012) terms as citizenship as shared fate. Ben-Porath means that democracy requires the citizens to realize that their own future is tied to that of the country. Hanson and Howe (2012) have discussed the important role of deliberative participation in civic The Georgia Social Studies Journal education arguing that such participation develops emotional connections and critical thinking. The elections as one such form of deliberative participation demand the attention of all citizens because the outcomes will impact them. Haas, Hatcher, and Szymanski Sunal (2008) pointed out that even primary children are both capable and need to have participatory activities in relation to elections. The campaigning, the emergence of people who want to be president, the conventions, and the election results are rich and exciting opportunities for teachers. By helping students connect to candidates, the classroom teacher can encourage young people to shake off the political apathy that increasingly plagues modern American citizens (Kahne & Middaugh, 2006). Using reliable, highquality websites in conjunction with time-tested pedagogical techniques, teachers can make a difference in the civic lives of their students. This process opens the door for students to learn about being active citizens. The purpose of the remainder of this article is to provide some experience-based ideas for active learning about presidential elections. Teaching about the Election Any number of activities may be designed to teach about the elective process itself. However, one of the life skills that students need to learn most is how to decide among candidates. Both the NCSS position statement on Creating Effective Citizens (NCSS, 2001) and the NCSS Social Studies Standards (2010) address civic responsibility, which includes being an informed participating voter. Kahne and Middaugh (2006) found high school seniors remain passive patriots at best near the culmination of their secondary education. When discussing the concept of being a patriot, we advocate going past a blind adherence to the righteousness of the United States to an approach that critically examines the complexity and contradictions in our democratic institutions (Westheimer, 2007). Activities which encourage students to think and act in relation to the election are likely to build more active citizens. According to Neumann (2012), candidates typically go through three phases: take the moral high ground; start making nasty allegations; talk about the mean spiritedness of the campaign (p. 178). How can students be lead to see this? In order to help students get beyond the rhetoric, teachers will first create a chart similar to the one shown here. They could use this chart as a model but they would need to define and discuss the items on it. Then, students could brainstorm other qualities that they want in a candidate. Wise teachers will be careful of being overly critical of student ideas, even when they do not fit their own more informed, adult views. Trait Weak Moderate Has the skill and character to be an effective president Personality Speaking skill Logic and ability to reason Looks presidential Honesty and integrity 39 Strong Very Strong The Georgia Social Studies Journal Ability to get along with others Experience Convincing and Winning Media Presence Positions on Issues (Add particular interest of concern to students) Once the chart has been developed and edited, students need to research the various candidates for president. They can use their research to evaluate the variety of individuals seeking party nominations. This allows students the opportunity to follow their favorite candidates through the primaries and to the national convention, mapping what happens to the candidates using a line graph to show their polling. This process can be duplicated with the two major party nominees that emerge. Different activities can be used to follow the election itself. Begin by having students in groups supplied with maps of the United States. Have the groups research and identify the number of electoral votes that each state gets. Each person within the group is responsible for finding the number of electoral votes for several states. Students should calculate this from numbering the senators and representatives each state gets and then filling in the appropriate numbers on the map. One website to visit is the Electoral College website (NARA, 2012). Then, allow students to research contributing factors to guess how those states will vote or distribute their electoral delegates in this election. Middleton (2012) has attempted to explain the interworkings of the electoral college in a student friendly way. Students can use the computer to find: how each state voted in the last presidential election or two, how strong the votes were in the primary, and other factors. Sites include the Red and Blue States Summary, http://www.vaughns-1pagers.com/politics/red-blue-states-summary.htm, (2012) and Historical Presidential Election Information by State, http://www.270towin.com/states (2012). After students have done their research, let each group fill in red and blue states, showing their prediction of which states will vote for the candidates from the two parties. The state maps can be the basis for discussion and debate among groups. Questions should be raised about the reasons that some states are consistently in one party and others are not, whether the parties of the governors and senators of a particular state are reflected in their presidential vote, and the role of the geographic location of a state. The day after the election students can use the reported election results as the basis to compare their own predictions. Getting to Know the Candidates Increasing diversity and decreasing political involvement make it more important than ever for teachers to provide ways for students to make personal connections with the candidates (Kahne and Middaugh, 2006). The “Getting to Know the Candidates” chart allows students to record the candidates’ personal information and stances on issues. To get started, brainstorm with students to determine specific personal information they would like to know about the candidates. Some personal information about the candidate could include party affiliation, education, previous careers, and political experience. Narrow the list by 40 The Georgia Social Studies Journal allowing students to vote on the issues for which they want to know the candidates’ positions. Students might name the economy, immigration, the environment, and energy policy among many others (See below). Getting to Know the Candidates Candidate's Full Name: _____________________________ Place Picture Here Political Party:_____________________________________ Age:______ Home City and State:_____________________ Previous Careers: ______________________________________________________________ Write one or two sentences describing the candidate's position on: The War in Afghanistan: _______________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ The Environment: _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ The Economy: ________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ Energy Policy: ________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ Write a quote from the candidate which represents him or her best. _____________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ Write 3 sentences telling your opinion of this candidate. Would you vote for this candidate?____________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ 41 The Georgia Social Studies Journal Create the chart with headings and blanks, and add open-ended questions that allow students to synthesize the information they have found. Some questions the teacher may consider are: What do you like and dislike about the candidate’s positions? With which of the candidate’s beliefs do you agree and disagree? The questions should direct, focus, and extend student thinking. Finally, have students access high-quality websites to complete their charts. The CNN Election Center (www.cnn.com/ELECTION/2012/) contains biographies, quotes, and the candidates’ stances on selected issues. The 2012 Presidential Candidates site (http://2012.presidential-candidates.org/) holds biographical information, but also has a "Head to Head" comparison page where students can select two candidates and compare them side by side on each issue. Other presidential websites are characterized by Risinger’s work (2012) and Clabough and Turner’s work (2011). By helping students connect to candidates, the classroom teacher can encourage young people to shake off the political apathy that increasingly plagues modern American citizens (Kahne & Middaugh, 2006). Using reliable, high-quality websites in conjunction with time-tested pedagogical techniques, teachers can make a difference in the civic lives of their students. Pants on Fire Awards Advertising has long been a key strategy in presidential election campaigns, and historically candidates have not always been honest in their advertising (Jamieson, 2012). Pants on Fire Awards is a classroom strategy in which students examine the accuracy of political candidates’ statements in their advertising. It is important that citizens have an informed understanding of their political candidates’ positions and not be swayed by false accusations. Citizens must critically examine both the pros and cons of candidates to reach an honest appraisal of a candidate (Kahne & Middaugh, 2007). Presidential commercials are an integral part of contemporary presidential elections. Living Room Candidate, http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/ , has collected all of the presidential commercials from the two major political parties since 1952 on their website. A common theme in the commercials from both political parties is attack ads. Some example attack ads include Peace Little Girl where President Lyndon B Johnson implies that Barry Goldwater is an extremist and Tank Ride where George H.W. Bush claims Michael Dukakis is weak on national defense (Museum of the Moving Image, 2008). Students should engage in activities where they grapple with the issues facing this country in meaningful and relevant ways (NCSS, 2001). It seems obvious when students do so that they are becoming active citizens in a democracy. PolitiFact, http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/rulings/pants-fire/, reviews the accuracy of politicians’ statements and gives Pants on Fire awards for inaccurate statements that distort the comments of others (PolitiFact, 2012). The idea of Pants on Fire Awards can be used by social studies teachers to examine commercials during a presidential election. The teacher selects commercials to have students view. After watching the commercials, students research the content for accuracy. They then give a Pants on Fire Award to commercials which are inaccurate or misleading. Students will more than likely be giving some Pants on Fire Awards. They can then create their own political commercials with The Living Room Candidate Ad Maker, http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/admaker/2008/sandbox, to correct the inaccuracies found in a presidential commercial. The Ad Maker allows students to add dialogue and images to create their own 30 second commercial. This process will allow students to work on their research skills by using a variety of media to demonstrate their comprehension. 42 The Georgia Social Studies Journal Presidential Speed Dating A prominent component of a presidential election is the debates between the two candidates, which allow them to reach a wider audience on their positions. Debates unfortunately often boil down to name calling and avoiding issues of substance (Neumann, 2012). Students need to be aware of issues that impact them on a local, state, and national level (NCSS, 2001). One activity to help students understand a candidate’s stances on issues is Presidential Speed Dating. With this activity, several students are selected to be a candidate. These students research a candidate’s position on different topics and give a brief presentation. The teacher sets up stations that students rotate through in small groups. Each student fills in a short graphic organizer as they learn information about a candidate at each station. After the students rotate through all stations, the class discusses what they learned about a candidate. The activity benefits students in several ways. First, students assume ownership of the learning by articulating a candidate’s beliefs in a short presentation. The classroom dynamic changes because students get up and move around the classroom throughout the activity. Issues are also explored in more in-depth by examining the beliefs of a candidate. Conclusion Kahne and Westheimer (2003) studied ten educational programs whose goal was to develop citizens. They found that if educators wish to foster a strong and committed sense of active citizenship in their students that it will not come from reading literature on citizenship programs. In fact, serious work is needed. Presidential elections provide a rich, motivating arena to develop citizenship skills and, more importantly, the spirit of good citizenship. There are countless opportunities for students to learn and practice research skills, especially those using the Internet. The activities that we have presented here should enable students to be more informed about the entire spectrum of the election process. The research involved in these activities can help students see through the rhetoric and showmanship of campaigns and candidates to see the issues of the people running for president. By getting students interested and involved in the elections, they can see the importance of this democratic process for our society and impact that their votes can have on shaping policy in this country and around the world (Noguera & Cohen, 2007). Above all, educators need to design and construct opportunities to develop a sense that students as individuals count in the democratic process. References Barr, R., Barth, J., & Shermis, S. (1977). Defining the social studies. Washington, D.C.: NCSS. Ben-Porath, S. (2012). Citizenship as shared fate: Education for membership in a democracy. Educational Theory, 62(4), 381-395. Citizenship Foundation. (2012). What is citizenship education? Found on line at http://www.citizenshipfoundation.org.uk/main/page.php?286. Clabough, J., & Turner, T. (2011). Questions, quests, and quizzical thinking. Social Studies Research and Practice, 6(3), 91-101. Haas, M., Hatcher, B., & Szymanski Sunal, C. (2008). Teaching about elections during a Presidential election Year. Social Studies and the Young Learner, 21, (1), 1-4. Hanson, J. S., & Howe, K. R. (2012). The potential for deliberative democratic civic education. Democracy in Education, 19, (2), 1-9. Hess, D., & Ganzler, L. (2007). Patriotism and ideological diversity in the classroom. In J. Westheimer 43 The Georgia Social Studies Journal (Ed.), Pledging allegiance: The politics of patriotism in America's schools (pp. 131-138). New York: Teachers College Press. Jamieson, K. (2012). Teaching critical thinking by asking “Could Lincoln be elected today?” Social Education, 76(4), 174-177. Kahne, J., & Westheimer, J. (2003). Teaching democracy: What schools need to do. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(1), 34-66. Kahne, J., & Middaugh, E. (2006). Is patriotism good for democracy? A study of high school seniors’ patriotic commitment. Phi Delta Kappan. 87(8), 600-607. Kahne, J. & Middaugh, E. (2007). Is patriotism good for democracy? In J. Westheimer, (Ed.). Pledging allegiance: The politics of patriotism in America’s schools (pp. 115-126). New York: Teachers College Press. Middleton, T. (2012). Demystifying the Electoral College: 12 frequently asked questions. Social Education, 76(4), 169-173. Museum of the Moving Image (2008). The living room candidate: Presidential campaign commercials 1952-2008. Retrieved from http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/. National Council for the Social Studies (2001). Position statement on creating effective citizens. Washington, D.C.: Author. National Council for the Social Studies (2010). National curriculum standards for social studies. Washington, D.C.: Author. Neumann, D. (2012). Flip-flopping, presidential politics, and Abraham Lincoln. Social Education, 76(4), 178-181. Noguera, P., & Cohen, R. (2007). Educators in the war on terrorism. In J. Westheimer (Ed.): Pledging allegiance: The politics of patriotism in America's schools (pp. 25-34). New York: Teachers College Press. PolitiFact.com (2012). Statements we say are pants on fire! Retrieved from http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/rulings/pants-fire/. Risinger, C. (2012). Teaching about the 2012 elections using the Internet. Social Education, 76(4), 187-188. U.S. NARA (2012). U.S. electoral college. Retrieved from http://www.archives.gov/federal-register/electoral-college/index.html. Vaughn’s Summaries. (2012). Red and Blue States Summary. Retrieved from http://www.vaughns-1-pagers.com/politics/red-blue-states-summary.htm Westheimer, J. (2007). Politics and patriotism in education. In J. Westheimer (Ed.), Pledging allegiance: The politics of patriotism in America's schools (pp. 171-188). New York: Teachers College Press. 270towin.com (2012). Historical presidential election information by state. Retrieved from http://www.270towin.com/states. About the Authors Jeremiah Clabough is an Assistant Professor of Education at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. His research interests include student engagement through role-playing activities and the use of primary sources in the social studies classroom. He can be contacted at Thomas N. Turner is a Professor of education at the University of Tennessee. He is the author of Essentials of Elementary Social Studies and author or co-author of five other books and over a hundred chapters and journal articles. 44 The Georgia Social Studies Journal Gary W. Cole taught social studies for ten year. He is currently an assistant principal at Sequoyah High School and a doctoral student at the University of Tennessee. His research interests include activities with ELL students and creativity in the social studies classroom. 45