PROGRAM NOTES Introduction The main purpose of this work is to

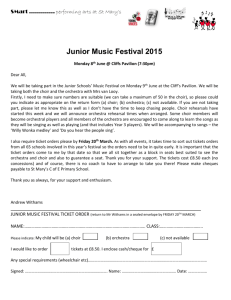

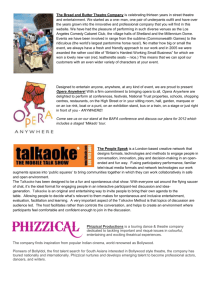

advertisement