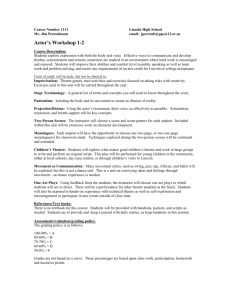

Vladimir Jevtović THE ACTOR IS ALIVE IN A LIVE THEATRE

advertisement

Vladimir Jevtović THE ACTOR IS ALIVE IN A LIVE THEATRE Theatre is a meeting place of actors and audiences. A theatre play is what happens between actors and audiences. The presence of both is necessary. There is no theatre play without an audience. But neither is there a theatre play without any actors. What is necessary is the contact between the two groups of living people, their immediate presence here, in the theatre or on stage, during a performance. If there is such a contact, it enables a dialogue, an exchange of energies, thoughts and emotions. An immediate, direct contact between actors and audiences is a quintessence of theatre, the feature which distinguishes it from other arts, film and television in particular. Regardless of the choice of content and form, regardless of the genre, or the type of stage space and auditorium, regardless of the acting technique, the type of actors’ education, for an interaction between actors and audience it is always necessary that the meaning of the events presented onstage is understood. The actor is the centre of the action, the master of the plot, the convergence point of all stage signs, the spectator’s guide through the development and course of dramatic performance. The actor has to be able to understand the meaning of what he/she is supposed to do on stage so that the same meaning can be readable to the spectator as well. Both the actor and the spectator need to grasp and accept the intention behind a certain scene, the entire performance as it is. It is impossible for a spectator to gain awareness of the director’s concept unless the actor himself is aware of it. Therefore, the actor is not an unaware agent between the director and the spectator. The actor, with his entire being, including his psycho-physical individuality, affects the entirety of the spectator’s being, his imagination, thoughts, emotions. Whether the theatre play has a narrative or not, characters of human beings, animals or plants, realistic or surrealistic, dreamlike or documentary events, it is always actors, and actors alone, that can, by their well thought out actions, affect spectators, and spectators can only respond to actors as kindred living beings on stage. It is resonance, recognition, sympathy. This contact and exchange between actors and spectators must, deeply and irreplaceably, be human and live. There is no object on the stage - set, costumes, props, lights - that can become alive without actors’ action. Everything on the stage is made alive through a self-aware act of actors. But acting is made possible only in a joined presence of the actor and the spectator. The process of performing and the process of accepting are complementary processes of exchange. The actor’s fundamental means of expression are voice and gesture. But these are just means of expressing the actor’s internal organic processes. The spectator would not be able to hear without a projected, audible voice of the actor, and could not see a physical gesture without the actor’s body which is capable of expressing action, but, nevertheless, the spectator receives the meaning of an action, its emotional tone – by means of voice, speech, face or body - from the actor’s inner self, and this encourages a parallel process in the spectator. Thus, the spectator is a resonator of the instrument of the actor. But, since the actor is a living instrument who feels and receives the echo of its resonator, it encourages him to continue the action already started with a heightened self-confidence, with a conviction that there is dialogue, sympathy, understanding established. Then there appear tears, laughter, catharsis or dead silence. Acting is born when actors, by their action, by a chain of activities with a certain meaning and aim, establish a contact with the audience, an undisturbed attention-exchange circuit between the stage and the auditorium. Live actors use their lives as the material they work with but they target for the life of spectators, their life potential. It is the psycho-physical resonances, experienced in the actor, which cause parallel internal experiences in the spectator. The feature typical of theatre is that actors’ internal action affects all spectators simultaneously and that, in the best of performances, spectators respond at the same time and in the same way. First comes internal experience, and then an external manifestation. Acting can, sometimes, homogenise audience to an absolutely uniform and general response. It is the deeply rooted principle of action and reaction at work which makes a theatre play possible. The actor is the bearer of the stage action, but also an initiator of the internal action in the spectator. This is where a sudden feeling of recognition of one’s private life on the stage comes from. This is why spectators easily identify with a dramatic character, after a significant, designed stage action. Just like Hamlet organises with actors the court play so that a man pours poison into the sleeping king’s ear, which makes the king-uncle and the queen–mother recognise their crime, we, too, at a certain point, see clearly the meaning of a single action and this initiates a chain of associations, memories and emotions. This is possible when we feel close to a dramatic character, when we recognise a certain situation. That is why we sometimes have a sense of a personal revelation, when we find a solution to an intimate secret of ours during a performance. The basic principle is that the actor enables a parallel experience in the spectator. Each actor’s word that is not justified by experience, which fails to provoke parallel experience, is a dead word. Each physical gesture of the actor without justification in facilitating understanding on the part of the spectator is a dead action. The phenomenon of acting is so elusive for the very fact that all external aspects are accessible to the spectator’s senses, rooted in the actor’s inner self and that spectator goes beyond the sensory experience of acting, where his psychophysical being has an internal response to the actor’s action. Acting is experienced both by senses and by soul. It is essential that the actor creates from his inner self, that his entire being is a source of the newly created value, that he is not a puppet which mechanically repeats the director’s instructions, that he is not an anchorman who is uttering, properly and neutrally, somebody else’s text, without any underlying subtext, that he is neither a model displaying his external qualities nor a parrot uttering again and again always the same text without understanding. BRANKO GAVELLA Branko Gavella, the great theatre director and important theoretician of acting, pointed out: “The actor’s personality, if he wants to completely penetrate the soul of the spectator, has to become in a certain sense normative for the spectator’s experience. It absolutely must be of interest to the spectator. Thus, it must be authoritative in all respects. It is only with becoming a person of authority that he becomes a person of artistic value.’(1) The actor has his material at his disposal. He is the only one who can have an insight into and control over his inner experience. He is the only one who can make a choice and decide which of the private, intimate elements he is going to make public, using this as a subtext or the meaning of a text and to convey it to the spectator. “The main purpose and aim of actors’ actions is to awaken our utmost organic, vital functions. We can let the actor in only when we experience his onstage representation with equal directness and clarity, with the same intensity as we do experience our own selves. This climax of concentration which means an absolute mutual penetration between the actor and the spectator is only rarely achieved.” (2) A live, self-aware actor is necessary for establishing a contact with a live audience. Life in theatre is a life in two, in a pair: the actor and the spectator. Having only one element of the pair is not enough. Actors are truly alive only if they manage to prove it by making the audience alive and creating a living performance together with them. Failure - if the content, the effect of the play, is not received and accepted by the audience - leads to misunderstanding in communication, boredom and dissatisfaction, resulting in a dead performance. Boring theatre is a dead theatre. Theatre without its audience is a dead theatre. Actors in such a theatre are dead, too. There is no one who wants to see them. There is no one to buy a ticket. The one who covers the costs of such a clinical death knows why he does it. An actor is alive when he is capable of carrying out, together with the troupe, the director’s idea, a score created at rehearsals, within the repertoire of his theatre, when his abilities allow him to play in a show which the audience finds interesting, attractive and important. Instead of misunderstanding and boredom, actors in a live performance guide spectators through an exciting, and sometimes unforgettable experience. Respect for the audience and its needs are the most serious element of any professional theatre’s ethical code, and the most important condition for a continuation of a live theatre play. This is a necessary constellation of a theatrical situation. An actor is certainly alive in a living theatre. And theatre, just like phoenix, lives through a chain of small deaths and rebirths. At the core of a dead theatre lies dead acting. The worst actor is a boring actor. The director who tolerates boring actors is a bad director. The audience who applaud to a boring, dead theatre is dead audience. Theatre is mortal. It dies evening after evening. Sometimes, it does not even become alive: it starts boring, and it lasts boring, until the spotlights are out. After a dead performance, a performance which failed to become alive, to establish a contact with its audience, a critic explains that there was a directing concept, but that the actors failed to carry it out, there was a concept, but the audience failed to understand it. Neither the actors nor the audience understood the concept. The critic did. Typical, healthy audiences are merciless: they leave at intermissions from a performance which has failed to become alive. On the other hand, the premiere audiences, who do not buy tickets, are full of concern, interest, reasons to play the role of interested audience even when they are not. But after several runs, actors know how much time their production has left and how long it will live. Even if some well-known form of infusion is applied. The production will, just like a sick person, suffer its destiny, with diminishing audiences, as long as the theatre owner decides to keep it on. Even when the numbers of audience are smaller than the number of actors onstage. PETER BROOK On 28th April 1983, at the Bouffes du Nord theatre in Paris, Peter Brook told me: “Life doesn’t exist without all superficial and external things, but it also does not exist without all deep and central things. This can be tested in the theatre. A performance must establish a contact. A performance which fails to establish a contact is not a performance. A performance is something that reaches the audience directly from the actor and many things are necessary for that: there must be understanding, there must be a shared language, there must be a shared influence, shared meanings and shared feelings. Therefore, if material enables understanding, in a very wide sense, then it yields pleasure, one way or the other. Then and only then, a performance exists. On the other hand, if all those things are lacking, if there is no understanding, there is no shared language, the balance is destroyed and the performance disappears.”(3) A Performance exists when the auditorium and the stage become one, when contact is established, an exchange between actors and the audience. A performance is born when the audience understand the meaning of the events on stage. Therefore, besides the outside aspect perceived by senses, internal aspect of the events on stage, received by mind and soul is also necessary. There are many ways, genres, styles of materialising the internal aspect of a play but the demand for ‘cleansing’ dramatic characters of psychology would have to be applicable to audiences as well – they, too, would have to be devoid of their own psychological life. There is no doubt that the consequence of limiting theatre to the external aspect of events on the stage alone, which would make professional actors redundant, would be a great loss for the audience’s experience. As their perception would be limited to the scope of the visible and the audible, to the sensory reception, ‘cleansed’ of all emotions and thoughts. Is such a venture possible and to what purpose? Why is it so important to prove that theatre is possible without actors? Why is the relationship-actor an obstacle to the ‘emancipation’ of theatre from ‘stage representation of fiction’? Who would be spectators in such an ‘emancipated theatre’? What would be the content of the spectator’s reception in such a theatre without actors? STANISLAVSKI The art of acting and acting profession are as old as man: the first appearance of the actor was in ritual dances and singing, and later with dialogue as well. In Greece, actors participated in religious ceremonies, and then in tragedies and comedies, whose popularity among the common people gained actors considerably high status. In Rome, their social position would suffer a decline – only slaves could be actors. In the 16th century a need for professional actors first appeared: Commedia dell’Arte troupes in Italy, Lope de Rueda in Spain, the first permanent theatre house in London, Burbage Theatre and the establishment of the first professional troupe in Hôtel de Bourgogne in Paris contributed greatly to the creation of conditions for a continuous engagement of actors. The art of acting started flourishing: Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Drama boosted British actors, Italian dell’Arte troupes toured all over Europe triumphing in Paris, Corneille and Racine with their tragedies, and Moliere and Marivaux with their comedies opened the doors for French actors to fantastic chances for success to French actors. In each of these periods, actors were met with different demands, depending on their task; demands for a certain skill, a quality needed for effectiveness in a certain dramatic genre: the Greek tragedian was completely static and had to possess a very resonant voice, articulated speech; the pantomime developed in Rome called for acrobatic flexibility. In Commedia dell’Arte the actor had to have an artful body, good reflexes and a sense of improvisation and humour. French tragedy appreciated pleasant, melodious voice, musicality and nice appearance. The melodrama of the 19th century could be effective only if actors, with their passion and emotiveness, were able to be suggestive to the spectators, while vaudeville was successful when actors were capable of acting fast, wittily, with precise characterisation and emphasised gestures. An actor from the turn of the 20th century could play Chekhov, Gorki, Ibsen, only if he mastered the psychology of his character. The Moscow Art Theatre made worldwide success on its tours because, due to Stanislavski, it found a psycho-technique which yielded extraordinary results: actors in dramatic characters were able to reach a fascinating level of persuasiveness. In Stanislavski’s school they searched for the stage truth, for a truth which would be credible to the audience. Within the limits of one method – realism, they sought to find an acting technique which yields the desired result. Stanislavski’s actors discovered how to turn their creative potentials into a power to create characters as real, living human beings. With the new understanding of acting, stage action (activity) as a series of designed gestures, leading to the materialisation of a precisely defined, desired goal – Stanislavski’s actors got the means of navigation, a lighthouse in the sea of arbitrariness. A stage task is a work order that has to be carried out throughout a theatre play. It stems from the understanding of the content of a dramatic piece, the director’s reading, harmonisation of the ensemble during the rehearsal process. Just like an actor learns how to breathe properly by observing babies breathe, the actor becomes a master of action by becoming aware of the obvious fact that every man, from getting up to going to sleep creates an uninterrupted chain, a series of actions aimed at a concrete end. And even when he is asleep, he continues this chain, but following the logic of dreams, either by ‘commenting’ on the experience already lived, or as an anticipation of what he will experience tomorrow. Of course, some or many of the day’s aims are not fulfilled. Obstacles include: other people’s will, lack of something necessary, daily human traffic where some people do not obey the rules. Every day, we enter the field of contact, perhaps of conflict, with a gallery of characters whose actions we cannot predict. I love someone who doesn’t love me, but loves someone else. Or only themselves. Every day, we try to harmonise our desires, our needs, with the others. Perhaps we fail but we do not give up. Chekhov’s characters constantly fail to reach satisfaction, harmony with others, because there is always someone else, who comes and prevents the pair from ‘stepping over the threshold’ and becoming a couple. Being pairless, loneliness, impossible loves, asymmetric relationships, emptiness. At the end of the day they feel tired. What is the sense of a day lived? Where is sense in a concrete character’s life? Stanislavski’s actors engaged in a serious and responsible exploration of the inner narrative of their characters, their emotions and thoughts, their states of spirit. From their own life, their own imagination, worldview, memory, they created characters who appeared alive, persuasive on the stage. Stanislavski systematised the basic, essential, fundamental elements of the craft of acting in the form of a practical guidebook which helps actors and acting pedagogues to do their job successfully. Stanislavski just provided practical instructions for achieving the best possible results. These instructions offer neither recipes nor a strict set of rules for any theatrical genre. Practice has proved as untrue that Stanislavski’s System is limited to realistic, psychological theatre only. There is a bridge from realism leading to all other genres, which enables further development of Stanislavski’s technique of acting, its ramification in different directions, from a common root. The influence of Stanislavski’s acting psycho-technique on the work of the Actors Studio and the results of a number of American film stars, alumni of the Studio, has brought a global affirmation of an acting method which met precisely the requirements of the medium of film, its era and its audiences. The demands for a certain acting technique change following the change of the audiences’ taste; the change of their needs, or a need to interpret new dramatic pieces appearing in different places. The modern actor must be prepared for all genres and all sorts of demands in theatre or film. He has to be physically fit, be able to control his body in action, be capable of quick thinking and instantaneous reactions, develop a strong emotional experience, develop his imagination – the source of his creation. He has to be ready to work with dedication all his professional life, always in accord with his partners. The balance of mental and physical aspect of his work, external and internal acting techniques improve selfconfidence and facilitates success in communication with audiences. GROTOWSKI How did Grotowski answer the challenges of his time? Starting from Stanislavski and aiming to test the key postulates of his method, Grotowski established the Laboratory Theatre where, under experimental conditions, he tested the basic elements of acting: the actor’s attitude towards the content at hand, the actor’s relationship towards the stage space, the partnership between actors, the actor’s effect on the spectator, relationship between the actor and the director. Grotwski sought a new key for the actor-spectator encounter, shaping, testing and materialising the Poor Theatre concept in his Laboratory Theatre. The poor theatre, as opposed to the rich or total theatre is a theatre which is stripped of any excesses. By rejecting all secondary means, the actor becomes the sole source of sound, light and music. All changes that happen on the stage come from actors alone. Thus, the scope of tasks and responsibilities are widened in both the preparatory and performance stages. Owing to strenuous exercise and dredging up the deepest intimate episodes associated with the stage action actors achieve maximum concentration, which is then conveyed to the audience bringing it into a state of hyper-attentiveness. Grotowski rejected the principle of realism, naturalism, as he jettisoned décor, costume of naturalistic theatre. However, what appeared is ‘super-naturalism’ in acting: Actors no longer play characters-models, but their own selves. What actors do is not an imitation of reality, a reconstruction of some previous life, nor a creation of someone else’s life (‘character’), but the reality itself, the actor’s act of self-discovery in the present. The Poor Theatre loses on one side but gains on the other: on the side of the actor’s play, the level of perception and the depth of the audience’s emotional experience. The Poor Theatre’s name can be interpreted ironically: the spectator’s experience is rich and existential. The reduction of external means enables production of an intensive actor’s action which amplifies the quintessence of theatre: a live actor-spectator relationship. The intensified presence of the Poor Theatre’s actor leads to an intensified presence of the spectator: it is an intensive contact and conflict between two human beings. Grotowski himself cited Stanislavski as his role model. A systematic expansion of observation methods, a dialectic attitude towards one’s own previous work, persistency in posing key questions of methodology which call for new answers – these are Stanislavski’s instructions adopted by Grotowski. “He was the first great creator of a method of acting in the theatre, and all those of us who are involved with theatre problems can do no more than give personal answers to the questions he raised.” (4) The attitudes shown by Grotowski in his final speech given after the 1966 seminar at the Drama School Skara in Sweden (5) and those of Stanislavski from the book ‘An Actor Prepares’ (6), which were based on his writings from the period between 1907 and 1914, are very similar or identical: about the contact, a dialogue with the partner, about the plot, about personal associations as initiators of the action, about the actor’s dedication to the task, about the strict work discipline, about a consistent adherence to the score, about the actor’s obligation to ‘refresh’ the role with different variations without disturbing the score of the narrative, about the obligation to pursue a full life and constantly expand the scope of his experience. The importance of small physical actions, muscle relaxation, release of extra tension and muscle contractions – all of these are elements of Stanislavski’s method which Grotowski adopted and developed further, offering his own answers. Grotowski is indebted to Stanislavski for his constant struggle against routine, automatism, the actor’s narcissism, and for the idea of the theatre as a place of confrontation between actors, actors and the audience, and actors with their own selves. Finally, Grotowski adopted as the main guideline of his work a direct instruction of Stanislavski’s: ‘In regard to the external appearance of a play – decoration, props, etc. – it is only worth as much as it contributes to the expressivity of the dramatic action, that is, to the art of acting, and it certainly cannot seek in the theatre the independent importance which famous painters who work for the stage would like to attribute to it.’ (7) Setting off from Stanislavski’s principle of the actor’s preparation, of identification with the character model, of using a subtext to bring to life the text that actor is supposed to interpret, Growski, after his explorations in the Laboratory Theatre, came to the conclusion that the actor should not simulate someone else, mimic. The actor is supposed to be himself, who he is. He should make an act of public confession. Identification is not the actor’s attempt to interpret a text given to him, quite on the contrary, the text should be chosen according to the traits, interests, psychophysical constitution of the actor. A text is to be cut, the sequence of lines changed, edited and transposed. What is sought is a situation in the text which is relevant for the actor, significant for him. The actor uses a text to reveal the truth about himself. As opposed to the actor in a traditional formation, a Poor Theatre actor is not supposed to be ‘someone else’, to bring to life a character model which he has created, but to use his role as an instrument of selfrevelation. The actor is not to mask himself - he appears on stage in person. Signs used by the Laboratory Theatre actors represent an articulation of the actor’s psychophysical individuality and are, therefore, unpredictable, original. Actors do not take their signs from their teachers or parents, but create them personally. The actor is neither a puppet nor a perfect mechanism for reproducing – he is a creator. His presence on the stage alone is enough for a play to be. Grotowski would compare a play to a liturgy of self-atonement, to a collective confession, to a ritual which shocks with its openness, sincerity and devotion. He shook the very basic postulates of theatrical aesthetics by rejecting conventions, sterile repetition of the old stage formulas. First, he eliminated the separation between actors and audiences and allowed their direct physical contact. This turned the entire auditorium into a stage where actors can involve spectators into the dramatic action. Second, he rejected all the excess elements: set design, lighting effects, recorded music, etc. Third, he introduced the precedence of the actor as the basic subject in creating a play. Forth, he established a new, higher standard for expressive acting means, both vocal and physical. He introduced daily exercises for actors. Fifth, he introduced radical treatment of the text, superstructure of the text developed into the score of a play. Grotowski believed that the theatre has a chance to survive a surge of new technological media if it focuses its attention to the actor-spectator relationship and utilises its main advantage: the direct, live contact between two human beings. The level of spectators’ experience can be amplified and heightened if personal psychophysical engagement of the actor is amplified during a play. The shift of the actor’s task from uttering text or his identification with an imaginary character to expressing his own personality, using a chosen situation which invites strong personal associations and emotional reactions which the actor directs towards the spectator, had significant consequences. Actors do not ‘utter’ but express themselves using their whole being, they use their entire body as a resonator for the production of voice, they express themselves using the language they discovered personally, which they have reached through practice, which is neither inherited nor can be left in legacy. The actor does not surrender to the character, but ‘lets it in and through’ himself. A Grotowski’s actor does not pretend, interpret, perform, he is nobody else, but has to act personally, persuasively and truthfully. Therefore, he has to attain a higher level of development of inner acting technique. Therefore, the actor has to have a pronounced personality, a capacity for individual creativity within a collective. An actor without personal initiative, without a strong personal coverage in all his actions cannot meet these higher demands. Peter Brook said about Grotowski: ‘While he was in the theatre, his contribution was immense in certain higher standards for actors: primarily in regard to the actor’s concentration, then an actual development of corporal abilities of actors and, most importantly – he developed creative possibilities for the use of body language. In a new, different way. This language is free from predetermined gesture patterns. This is major: the body is not here to repeat an already known and predetermined stylised language, like in the oriental theatre, but to be used by the actor to freely and creatively express his own impulses in a certain situation, through motions in his own individual and original way. So, what makes him the greatest, after Stanislavski, is the establishment of new, higher standards for actor.’ (8) Did Grotowski, as a consequence of setting higher requirements for his actors, demanding from them to be creators, to assume greater responsibility for the effect of the play on the spectator, diminish the importance of the director in the theatre? The director, according to Grotowski, must have a moral authority so that he can assist the actor. A relationship of mutual trust is necessary. The director is an older brother to the actor, a spiritual leader, a guide in his voyage through encounters with new experiences. The director is also a judge in conflicts, an advisor who silently waits for the actor to turn to him for advice. As opposed to the director of concept who, seated at the table, puts together the mise-en-scene after the rehearsal, a Laboratory Theatre director animates collective exercises, leads training sessions, animates exploratory actions and creates conditions for a collective creation. He is a director who lives with the actors. The director is not engaged to stage a play in six weeks, but stays with actors, following all the steps of development and existence of a play. He travels with the play and shares all situations with his ensemble, he knows and understands actors, each and every one of them. This criterion was, besides Grotowski in the Laboratory Theatre, fulfilled by Peter Brook in his Centre for Theatre Research in Paris and Eugenio Barba in the Odin Teatret, in Holstebro, Denmark. Grotowski’s influence on the global theatre map was huge. It inspired the establishment of alternative groups, experimental stages, often outside of the theatrical mainstream in the given country, but very active in the chain of new theatrical festivals all over the world. One of them is BITEF in Belgrade, where Grotowski won an award at the first festival in 1967 with his play ‘The Constant Prince’ by Calderon. This production, together with the round table discussion with Grotowski, was very important for our theatre, but primarily for us, students of the Academy of Theatre Radio and Film in Belgrade. Grotowski’s work resulted in a strong encouragement for the development of alternative theatre, a shocking stimulus for acting schools, for theatre studies about acting ethics and technique, about the actorspectator relationship and the actor-director relationship. Joseph Chaikin, a Living Theatre actor and the founder of the Open Theatre said: ‘In the person of Jerzy Grotowski I got to know a poet who imbued acting with deeply humane sense. His inspiration and powerful sincerity made a deep impression on me just like they influenced so many theatre practitioners. The friendship and respect he aroused in me turned my hardcore scepticism into an actual instance of ‘brotherhood’. (9) Therefore, Grotowski was not and certainly could not have been an initiator of the movement for substituting an actor for a performer, a dancer, an amateur without education, either in an acting school or in theatrical workshops. It was not Grotowski who contributed to the separation of ‘fixation on the character with its psychology’ in order to free the audience from ‘dramatic fiction, perception of characters and other elements of narrative.’ It was not Grotowski who tried to get rid of the actor because of his ‘natural inclination’ towards a dramatic character with psychology. On the contrary. Grotowski, aged 26, studied and graduated acting and directing in Krakow, and then directing in Moscow. Starting from the question posed by Stanislavski, who has tested all the postulates of his System personally, in practice, as an actor and director, Grotowski set off to explore practically himself, seeking his own answers, trying to respond to the challenges of his own time and environment. Working on all the plays at the Laboratory Theatre, Grotowski discovered and consistently implemented the principle of elimination: ‘The theatre, therefore, can abandon decor, fake noses, made up faces, playing with lights, music and all possible technical effects. But the theatre cannot abandon the actor, his partner or the audience. The distinctive feature of the theatre, its distinctive score, inaccessible to other arts, is a score of human impulses and reactions, the psychological process caused by the corporal and the vocal of human beings. This is where essence of the theatre lies (...) Lost in external visuality, unbridled in a wild cacophony of concrete music, the total theatre loses the pure and reserved essence of the theatre. As opposed to this galvanic theatre of abundance, there is a theatre of poverty and deprivation. The universe of this theatre is inhabited by impulses and reactions. Not an accumulation of effects, but, on the contrary, their rejection.’ (10) THE ACTOR’S PRESENCE The actor is also always present in the exchange of energies with spectators. His presence is the condition of his effect on the spectator. There is no contradiction between his presence and ‘his stage presentation of fiction’, that is, characters ‘taken as a representation of psychological entities.’ The actor is always selfaware, regardless of the type of theatre he plays in. The self-unaware actor is not an actor but a pretender, a would-be-actor, a wanderer who has gone astray and does not know what he is doing or why, a surrogate. The self-unaware actor cannot touch the audience, he lacks persuasiveness. He cheats and lies and is therefore always unsuccessful. Acting is a dialogue between actors and the audience. If there is a contact between them, if the spectator accepts the actor’s suggestion that he is actually someone else, like in a children’s game, for a while, the actor will act like the character, walk like him, speak like him, look like him, think and feel like him. It is only possible provided there is an unspoken understanding between actors and the audience. The character does not exist if the spectator fails to recognise it, if he does not believe the actor that he has become, for some time, somebody else. It is part of a great game happening only on the level of imagination. The actor is the only one who really exists, while the character is merely a materialised creation which comes from the actor’s imagination. The character exists only because the actor used the right means to successfully persuade the audience that he is, for the duration of the show, Hamlet, Laertes or Claudius. The actor never disappears, immersing completely in his character. He only plays the character. The spectator is also selfaware, he also knows exactly what he is doing and why he is interested in the development of stage events, the plot, the ‘narrative’. The actor is everything he manages to persuade the spectator he is. Not only a character of a human being with a certain ‘psychology’, but he can equally be a wind or a little prince on a distant planet or a laughing ant. The imagination of the actor and the spectator is limitless, but they must be allies. There is no third party who will dictate rules of the game they so eagerly play. A judge can only stop the play which does not meet his standards. Authorities can close a theatre, forbid actors, or socially or morally anathemise the theatre which refuses to fulfil their demands. But audience is the one to decide which theatre is alive and which is dead, because it is the audience that enables it to be alive. It goes without saying that the actor, through the process of education, must learn to control the closeness or distance from his character, for the entire duration of a play’s life. Just like he puts on make-up and costume, getting into his character before a show, he enters the stage, stepping into some other reality, and after the show, he takes the make-up and costume off, leaving his character in the dressing room, and he goes home. Therefore, the actor has to get close to the character he is interpreting, to become him, only during rehearsals and performances. In a certain sense the actor, by his own volition, lends his own self to his character. If he is studiously dedicated to this embodiment, the audience will accept him as true and persuasive. The actor should treat his characters as allies, but should never think it would be better to stay in the character forever. However, the actor can find consolation in the fact that he can be his character every time when the play is on the repertoire, and an audience is present. EDWARD GORDON CRAIG Do we no longer need the actor in the contemporary theatre? In the first English theoretical book about the theatre ‘On the Art of the Theatre’ published in 1905, Edward Gordon Craig claims: ‘The whole nature of man tends towards freedom; he therefore carries the proof in his own person that as material for the Theatre he is useless. In the modern theatre, owing to the use of the bodies of men and women as their material, all which is presented there is of an accidental nature. The actions of the actor’s body, the expression of his face, the sounds of his voice, all are at the mercy of the winds of his emotions: these winds, which must blow for ever round the artist, moving without unbalancing him. But with the actor, emotion possesses him; it seizes upon his limbs, moving them whither it will. He is at its beck and call, he moves as one in a frantic dream or as one distraught, swaying here and there; his head, his arms, his feet, if not utterly beyond control, are so weak to stand against the torrent of his passions, that they are ready to play him false at any moment.’(11) As art is created according to a predetermined plan, man is not a reliable material for the execution of the plan, for the creation of art. The art of the future can provide better material, freed from emotions, thinking, its will, its personality. That is an ‘Über-marionette’. For Craig, the actor is a slave to his emotions. For him ‘the mind of the actor, we see, is less powerful than his emotion, for emotion is able to win over the mind to assist in the destruction of that which the mind would produce; and as the mind becomes the slave of the emotion it follows that accident upon accident must be continually occurring. So then, we have arrived at this point: that emotion is the cause which first of all creates, and secondly destroys. Art, as we have said, can admit of no accidents. That, then, which the actor gives us is not a work of art; it is a series of accidental confessions.’ (12) A professional actor has control over his voice, his face and his body. The actor presents on stage a series of purposeful, designed, meaningful actions. Actors’ actions are always purposeful. An actor who is a master of his craft wants to be onstage as much as possible, to work as much as possible, and it is not possible if his actions are unpredictable, if he misfits the score of the play, if he acts unreliably and creates chaos! Craig claims: ‘The nature of human body makes it unsuitable to serve as an instrument of art.’ (13) He claims that it hinders the development of the theatre but believes that the actor of the future will abandon the personification of a character and discover a new style. Then, the actor, just like a musician or painter, instead of imitating nature, existing things, will be able to communicate the essence of an idea to the audience, the spirit of the thing, but not necessarily the thing itself. ‘The painter means something rather different to actuality when he speaks of life in his art, and the other artists generally mean something essentially spiritual; it is only the actor, the ventriloquist, or the animal-stuffer who, when they speak of putting life into their work, mean some actual and lifelike reproduction, something blatant in its appeal.’ (14) Why must actors necessarily associate the idea of life with reality? Because actors personally exist as alive entities in reality. Because the life of actors is the source of their creation in their profession. Because actors are the only ones to use their bodies and their souls, their actual physical as well as mental dimension in a concrete, precisely defined temporal-spatial context. The actor is his own instrument. Everything on stage is three-dimensional. And everything lasts for a certain, limited period of time. The essence of the art of the theatre is based on contact, understanding, on the resonance between the life pulsating on stage and in auditorium. To cancel any of these two pulses would mean to cancel the theatre itself. To substitute an actor with a puppet of any kind would be the same as to substitute the audience with pretty dummies, with pre-recorded responses, such as the recorded laughter and applause in popular television sit-coms. If the only true artist in the theatre, the only author, like a painter or an architect, is the director who seeks to carry out his concept, his plan, using all means available to avoid ‘chaos’, ‘whimsicality’, then after we have substituted actors with puppets manipulated by him personally, the director could substitute the audience, too, with puppets which applaud when, and as long as he wants. The only remaining thing for him is to write his own review. 105 years ago, Craig announced: ‘Do away with the actor, and you do away with the means by which a debased stage-realism is produced and flourishes. No longer would there be a living figure to confuse us into connecting actuality and art; no longer a living figure in which the weakness and tremors of the flesh were perceptible. The actor must go, and in his place comes the inanimate figure—the Über-marionette we may call him, until he has won for himself a better name.’ (15) LONG LIVE COMPUTER! Today we have this better name. It is the computer-generated imagery (synthespians) or the digital ‘actor’ (computer-generated imagery CGI). The actor is no longer alive, he is a computer. The author is a computer artist, who indeed materialises his plan, like a painter or composer with his colours, notes and other obedient materials. I can imagine Craig rejoicing at this progress. But it is a Pyrrhic victory. The actor is dead, but the theatre is dead, too. All the new technologies happen on the screens where audiences can only establish a virtual contact with electronic partners. The essence of the theatre – a live contact – has been lost. The progress continues, but without the theatre. And the theatre, just like a phoenix bird, will rise renewed again somewhere – where audience needs it, for the same reasons that made it repeatedly die and appear reborn once again so many times in the past. This subterranean river will spring in some new unexpected place, to the pleasure of those who seek it. The theatre reappears and survives because, owing to favourable conditions, there appears a need that the theatre can satisfy best. Certain booms in the history of the theatre such as the appearance of Greek Drama in Pericles’ time, the blooming of Elizabethan Drama during Queen Elizabeth’s reign, the activities of Corneille, Racine and Moliere at the time of the Louis dynasty’s absolute monarchy in France, the Spanish Golden Age, all show that the theatrical form, architecture, dramatic text and acting techniques are no more but means for an optimal satisfaction of the needs of the audience, of accomplishing the desired mission. It is not the decrease in the numbers of audience from Epidaurus to Grotowski that is the goal in itself; it is only a tool for achieving a particular effect on a particular audience, in its own era. Grotowski did not establish his Poor Theatre on some narcissist, ascetic whim, but with a plan to prove that contemporary theatre can survive faced with new, richer technologies, with the total theatre, with total directors who behave as if they were on film not in the theatre. Grotowski proved that the horizon of the contemporary and the future theatre is an actor who is absolutely dedicated to his self-perfection, true to his partners, actors and the director, his content (which is not necessarily a narrative, but rather a ritual event of an exchange of high-voltage energies with his audiences). There is a long line of misunderstood theatre geniuses, those self-proclaimed revolutionaries of the theatre who discover new horizons only to watch audiences leave their experiments or shows because they are bored. The only true jury which passes a judgement on any act of the theatre is the audience, from a monarch to a student in the last row in the balcony. A theatrologist or a critic can state his criteria of the ‘radical artistic theatre’, make a distinction between experimental, artistic and commercial, folk theatre, he can, in his texts, promote his own value scale, but each and every member of the audience will make his own opinion of the show he is watching, and if he disagrees with the critics opinion, the spectator will no longer read his texts, but will not cease going to the theatre or give up watching the shows he has a need for. Theatrologists interpret the world of the theatre but cannot change it. Similarly, an actor on stage proves his qualities for which he was chosen, and he is always the chosen one. Formative roads of actors can take different routes: some receive formal education and then they further their knowledge in workshops, some only attend workshops, and others have neither formal nor workshop education such as some of the great stars of London’s West End. Each actor auditions here and now – to prove what he is able to do onstage. Some of them are highly educated and possess encyclopaedic knowledge, while others have no clue about who Brecht or Meyerhold were. That is the reason why some excellent acting students barely get a pass in theoretical-historical courses (‘the actor’s D’) at university, but that does not prevent them from enjoying a successful career, while some acting students with the best grades at university have no work later. Some of the best students never graduate because they have no need for a diploma to document the skills they have already proven onstage or in front of the camera. Theatrologists can, on the theoretical level, provide guidelines of a future course of the modern theatre, but that cannot have any impact on the theatrical practice. In this sense they can regret the fact that the actor is still a necessary, essential element of a play, while the actor-audience relationship is the only unavoidable constellation of a theatrical situation. There is not merely a need, but a necessity for the contemporary actor in the contemporary theatre. There cannot be a live theatre play with dead actors or non-actors. A live play is only possible with - both actors and audiences alive! Long live the actor in a live theatre! REFERENCES: 1. Branko Gavella: Teorija glume, od materijala do ličnosti, CDU, Zagreb, 2005. p.197 2. Branko Gavella: Glumac: kazalište, Sterijino pozorje, Novi Sad, 1967, p. 40 3. Vladimir Jevtović: Siromašno pozorište, FDU and Naučna knjiga, Beograd, 1992. p.187. 4. Ibid, p. 15 5. Jerzy Grotowski: Towards a Poor Theatre/Ježi Grotovski. Ka siromašnom pozorištu, ISS, Beograd,1976. 6. Stanislavski: Sistem, Partizanova knjiga, Beograd, 1982. 7. Ibid, p. 346 8. Vladimir Jevtović: Siromašno pozorište, FDU and Naučna knjiga, Beograd, 1992. p.192 9. Joseph Chaikin: The Presence of the Actor/Prisutnost glumca, Sterijino pozorje, Novi Sad, 1977, p. 21 10. Ludwik Flaszen: Apres l’avant-garde, Institut Theatre Laboratoire,Wroclaw, 1968. p.6 11. Edward Gordon Craig: On the Art of the Theatre/O umjetnosti kazališta, Prolog, Zagreb, 1980, p. 52 12. Estetika modernog teatra, priredili: Radoslav Lazić i Dušan Rnjak, Vuk Karadžić, Beograd, 1976, p. 177 13. Ibid, p. 179 14. Ibid, p.181 15. Ibid, p. 190