Chapter 1 The Philippines

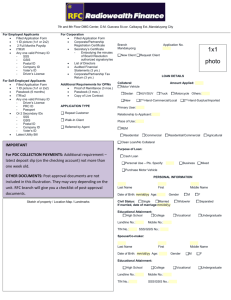

advertisement