Lingle Lingering: Seven Years after the United States Supreme

advertisement

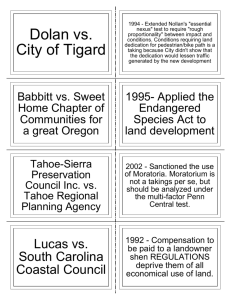

appropriation or the physical invasion of private property.5 Reviewing historic takings jurisprudence, the Lingle opinion recognizes the two distinct types of regulatory takings claims: (1) categorical or per se takings resulting from a loss of all economically viable use of property and (2) all other claims, requiring factual, ad hoc inquiries. Under the former, the Court determines whether the challenged regulation deprives a property owner of economically beneficially use of property. If so, just compensation is required under the Court’s holding in Lucas v. South Carolina Coast Council.6 Under the latter, the Court conducts a factual inquiry to gauge the impact of the regulation, utilizing the three nonexclusive balancing considerations set out in Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York7 to determine if the regulation “goes too far:” (1) the regulation’s economic impact on the claimant, (2) the extent to which it interferes with distinct investment-backed expectations, and (3) the character of the government action (hereinafter, regulatory takings requiring Penn Central’s ad hoc factual inquiries are referred to as “Penn Central takings”). The Lingle Court then identifies a common touchstone to the three inquiries that are not actual appropriation (physical invasion, deprivation of all economic use, Penn Central takings): “Each [inquiry] aims to identify regulatory actions that are functionally equivalent to the classic taking in which government directly appropriates private property or ousts the owner from his domain.”8 After presenting an overview of takings jurisprudence and recognizing the common touchstone, the Court moved into an analysis of the Agins v. City of Tiburon “substantially advances” test. In the 1980 Agins opinion, the Court had announced: “[T]he application of a general zoning law to particular property effects a taking if the ordinance does not substantially advance legitimate state interests … or denies an owner economically viable use of his land.”9 Following the Agins opinion, courts had used the “substantially advance” clause as a standalone regulatory takings test existing independently of Penn Central’s three factors; however, the test does not – like the other three tests do – identify regulations that are “functionally comparable” to government appropriation or invasion of private property. Rather, the substantially advances test suggests a means-end test that inquires into how “effective” the regulation is at achieving legitimate public interests. In Lingle, then, the Court rejects the “substantially advances” test for the purpose of takings analyses because it “prescribes an inquiry in the nature of a due process, not a takings, test, and [has] no proper place in our takings jurisprudence.”10 After removing the substantially advances clause from takings inquiries, the Lingle Court concludes by announcing the remaining field of takings analyses: Lingle Lingering: Seven Years after the United States Supreme Court’s Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc., Washington Courts Have Not Reformed the State’s Regulatory Takings Test By Paul J. Dayton and Leslie C. Clark, Short Cressman & Burgess PLLC In May 2007, the authors of this article published in this Newsletter a Fifth Amendment takings article addressing the 2005 United States Supreme Court opinion, Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc.1 That article complained that Lingle’s extraction of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from Fifth Amendment regulatory takings analyses remained unapplied in Washington courts. Now five years later, the same is still true. This article reminds of how the Washington regulatory takings analysis must change in light of Lingle. I. Background: Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc.’s Extraction of Due Process Considerations from Regulatory Takings Claims In Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc., the United States Supreme Court extracted substantive due process analyses from takings analyses and articulated the takings theories under which plaintiffs may proceed. The case began when Chevron challenged Hawaii’s new statute regulating gasoline leasesholds claiming, among other things, that the statute’s 15 percent rent cap effected a taking of Chevron’s property in violation of both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The federal district court granted summary judgment to Chevron, applying the “substantially advances” takings test articulated in Agins v. City of Tiburon.2 Specifically, the court held that “Act 257 fails to substantially advance a legitimate state interest, and as such, effects an unconstitutional taking in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.” After two appeals, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the award of summary judgment to Chevron, with a dissenting opinion contending that the Act should not be reviewed under the “substantially advances” standard.3 The Supreme Court granted certiorari and reversed.4 The opinion begins with a reminder that the Takings Clause does not prohibit the government from taking private property but, rather, places conditions on such takings: the taking must be for public use, and the government must provide just compensation to the property owner. The Court then observes that the “paradigmatic taking” requiring just compensation is a direct government May 2012 13 Environmental & Land Use Law We hold that the “substantially advances” formula is not a valid takings test, and indeed conclude that it has no proper place in our takings jurisprudence. In so doing, we reaffirm that a plaintiff seeking to challenge a government regulation as an uncompensated taking of private property may proceed under one of the other theories discussed above – by alleging a “physical” taking, a Lucas-type “total regulatory taking,” a Penn Central taking, or a land-use exaction violating the standards set forth in Nollan and Dolan.11 Guimont Step 2: Only if answers to the threshold questions allow continued inquiry, the court conducts a takings analysis. The takings analysis, in turn, has two parts: (1)The court asks whether the regulation “substantially advances” a legitimate state interest. [This is the same test rejected in Lingle.] If the answer is “no,” the regulation is a taking, and the analysis ends. If the answer is “yes,” the court proceeds with a balancing test. As explained below, this reassurance from the Court—that despite the rejection of the “substantially advances” test plaintiffs still have available the three regulatory takings challenges for a “physical” taking, a “total” taking, and a Penn Central taking—remains out of reach to a Washington state court plaintiff litigating a Fifth Amendment takings claim. (2)If the inquiry continues, the court engages in the ad hoc takings balancing test established in Penn Central in which the court considers: II. Contrary to Lingle, Washington’s TwoPart Threshold Inquiry Bars Many Plaintiffs from Proceeding on a Fifth Amendment Taking Claim. 1. The regulation’s economic impact on the property; 2. The extent of the regulation’s interference with investment-backed expectations; and, In its 1993 Guimont v. Clarke opinion,12 the Washington Supreme Court established a mandatory, ordered analysis to be followed by every plaintiff advancing a Fifth Amendment takings claim. Under Guimont, Washington’s analysis for Fifth Amendment takings claims13 sends plaintiffs through the initial double hurdle of a two-part “threshold inquiry” before posing the “substantially advances” inquiry as a final gatekeeper before plaintiffs may litigate the merits of a Penn Central regulatory taking claim: 3. The character of the government action. If, after balancing these considerations, the court determines that a taking has occurred, just compensation is required. Thus, Guimont requires the satisfaction of two threshold inquiries and an affirmation that a challenged regulation substantially advances a legitimate state interest before state courts ever even reach Penn Central’s factual inquiry. Under Lingle’s clear pronouncement that due process and takings analyses should no longer commingle, the Guimont test is constitutionally invalid. In addition to retaining the rejected “substantially advances” inquiry, Guimont’s second threshold inquiry sounds in due process reasonableness rather than regulatory takings because it provides no help in determining whether the regulation is the “functional equivalent” of a government appropriation or invasion. Finally, the existence of Guimont’s two “threshold” inquiries bars a plaintiff from immediately making out a Penn Central regulatory takings claim when, as quoted above, the Lingle Court had been careful to reassure Fifth Amendment takings plaintiffs of the remaining, direct availability of the Penn Central test. Guimont Step 1: The court engages in a two-part threshold inquiry. (1)Does the challenged regulation destroy or derogate a fundamental attribute of property ownership including the right to possess, to exclude others, to dispose of others, or to make some economically viable use of the property. If the answer is “yes,” the court conducts a takings analysis. If the answer is “no,” the court proceeds to the second threshold inquiry. (2)Does the challenged regulation safeguard the public interest in health, safety, the environment or the fiscal integrity of an area, or does the challenged regulation seek less to prevent a harm than to impose on those regulated the requirement of providing an affirmative public benefit? If the answer is “the regulation seeks more to impose on those regulated the requireMay 2012 ment providing an affirmative public benefit,” the court conducts a takings analysis. If the answer is “the regulation seeks more to safeguard the public interest,” there is no taking, and the analysis ends. 14 Environmental & Land Use Law III.The Washington Courts’ Adherence to the Guimont Construct Blocks Litigants from the Lingle-Endorsed Direct Takings Analyses. claimed that a newly-acquired parcel should have been deemed buildable. Although his as-applied challenge was not yet ripe, the court laid out the structure of the takings analysis, again citing Guimont’s two-part threshold inquiry and the Linglerejected “substantially advances” test without even acknowledging the applicability of Lingle. 2005: City of Des Moines v. Gray Businesses, L.L.C., 130 Wn. App. 600, 124 P.3d 324 (2005). The dissent in Gray Businesses recognized that Lingle simplified the takings analyses, suggesting that the Lingle test would ultimately replace the Guimont structure. Since the Lingle decision—now nearly seven years old—Washington has not altered its inconsistent Guimont Fifth Amendment takings claim construct. As a result, and as illustrated in the following examples, takings challenges decided in Washington state court have been curtailed. 2011: Thun v. City of Bonney Lake, 164 Wn. App. 755, 265 P.3d 207 (2011). In Thun, the plaintiff claimed a taking under Article I, Section 16 of the Washington Constitution when undeveloped property he owned was downzoned from allowing 20 housing units per acre to only allowing one housing unit per 20 acres. Division II of the Court of Appeals correctly noted that Lingle had removed the “substantially advances” test from the federal courts’ constitutional analysis, but it declined to apply Lingle to the state constitutional claim, continuing to follow Guimont. 164 Wn. App. at 760 n.4 (“the effect of [Lingle] on takings claims under the Washington Constitution is as yet undecided”). There are two fundamental problems with Thun’s announced divorce of Lingle from the state takings claim that was alleged. First, the Guimont test is a federal Fifth Amendment takings claim test, not a Washington state constitution test.14 Second, here was an opportunity for the plaintiff to argue that the state constitutional takings provision must be interpreted to afford him at least as much takings protection as available under the Fifth Amendment. In other words, if Lingle means that a Fifth Amendment takings plaintiff can proceed directly on a Penn Central regulatory analysis, then so must a parallel state constitutional provision. 2011: Star Northwest, Inc. v. City of Kenmore, 2011 Wn. App. LEXIS 800 (Apr. 4, 2011).15 In an unpublished opinion, Division I of the Court of Appeals affirmed summary judgment dismissal precluding the plaintiff from advancing its Penn Central regulatory takings claim. The court determined that the plaintiff, as the owner of a social card room, operated a “vice-like” business the closure of which—by nature of gambling’s historical disfavor—yielded a “no” under the second Guimont threshold test, ending the Guimont analysis. Division I acknowledged the plaintiff’s argument that part of Guimont’s analysis did not survive Lingle, but it declined to examine or apply Lingle. 2011 Wn. LEXIS 800 at *21, n.31. The Washington Supreme Court denied review. 2011 Wn. LEXIS 729 (Sept. 7, 2011). Thus, plaintiff Star Northwest was deprived of its day in court to put on its evidence supporting the three Penn Central factors. A proper application of Lingle would have allowed Star Northwest this access to justice. 2011: Olson v. Pierce County, 2011 Wn. App. LEXIS 256 (Jan. 25, 2011). In an unpublished opinion by Division II of the Court of Appeals, a landowner May 2012 IV.Conclusion The United States Supreme Court’s opinion in Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc. demands alteration of Washington’s Guimont v. Clarke takings analysis. The two-part threshold inquiry prevents plaintiffs from reaching Penn Central regulatory takings analyses. Even plaintiffs who succeed beyond the two-part threshold inquiry remain subjected to the “substantially advances” question squarely rejected in Lingle. Now seven years after the Lingle decision, the Washington Supreme Court should soon hear and decide a regulatory takings claim case that presents the Court with an opportunity to extract due process inquiries from Washington courts’ takings analyses. Paul J. Dayton and Leslie Clark chair the Commercial and Appellate Litigation practice group at Short Cressman & Burgess PLLC. Paul and Leslie have represented both public and private sector clients on issues relating to the Fifth Amendment takings clause and previously wrote on this subject in the May 2007 issue of this publication. 1 544 U.S. 528 (2005). 2 447 U.S. 255 (1980). 3 Id. 4 Id. 5 Id. at 536-37. 6 505 U.S. 1003 (1992). 7 438 U.S. 104 (1978) (hereinafter “Penn Central”). 8 544 U.S. at 540. 9 447 U.S. at 260. 10Id. at 540. 11Id. 12121 Wn.2d 586, 854 P.2d 1 (1993). 13The Guimont court clarified that its decision addressed only takings claims brought under the Federal Constitution, as the plaintiffs had not engaged in necessary briefing of the analogous State Constitution provisions. 14See footnote 13 supra. 15The authors disclose that they represented the plaintiff-appellant, Star Northwest, Inc., in the litigation against the City of Kenmore. 15 Environmental & Land Use Law