ResearchNotes - Cambridge English

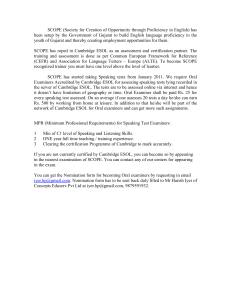

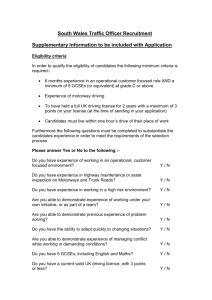

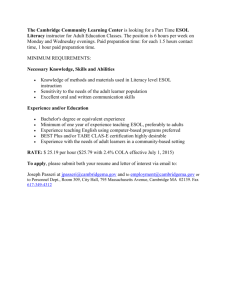

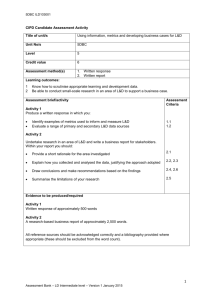

advertisement