PLESSY V. FERGUSON

advertisement

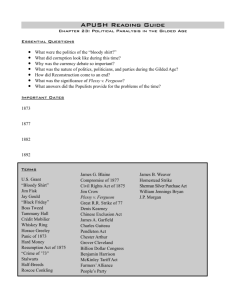

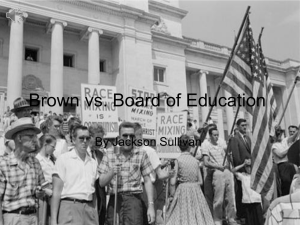

Title: Plessy v. Ferguson Author(s): J. Morgan Kousser Source: Dictionary of American History. Ed. Stanley I. Kutler. Vol. 6. 3rd ed. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2003. p370-371. Document Type: Topic overview Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2003 Charles Scribner's Sons, COPYRIGHT 2006 Gale, Cengage Learning Page 370 PLESSY V. FERGUSON PLESSY V. FERGUSON, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). African American activists and eighteen black members of the Louisiana state legislature of 1890 organized to defeat a bill requiring racial segregation on railroads by trading votes with white Democrats on the issue of a state lottery. When the "equal, but separate" law passed, the lawyer and editor Louis A. Martinet marshaled much of the group to test the law's constitutionality. They hired the white Reconstruction judge and popular novelist Albion W. Tourgee as the organization's lawyer, and recruited Homer Plessy to board a railroad car reserved for whites. Arrested by arrangement with the railroad company, which wished to avoid the expense of maintaining separate cars for patrons of each race, Plessy was arraigned before Orleans Parish Criminal Court Judge John H. Ferguson. Tourgee argued that segregation contravened the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, because it was a "badge of servitude" intended not to separate the races (black nurses could travel with white employers) but purely to emphasize the blacks' subordinate status. It was also arbitrary and unreasonable, because it allowed mere railroad conductors to determine a person's race, and because race had nothing to do with transportation. After Judge Ferguson and the racist Louisiana Supreme Court rejected or sidestepped these arguments, Tourgee appealed to a U.S. Supreme Court, which was undergoing an unusually high personnel turnover, adding five new justices during the four years that Plessy was pending. Different appointments might have led to a different decision. As it was, the Louisiana law was upheld seven to one, with four of the positive votes coming from members of the more racist Democratic Party. The arguments—between justices Henry Billings Brown of Michigan for the majority and John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky in dissent—came down to three basic points. First, Brown thought racial separation and social inequality natural and unalterable by statutory or constitutional law, while former slaveholder Harlan pointed out that it was Louisiana law, not custom, that imposed segregation here. Stealing a phrase from Tourgee's brief, Harlan announced that "Our Constitution is color-blind." Second, the justices disagreed on whether the separate car law had an invidious purpose, the northerner denying it, but the southerner knowing better. Third, Brown ruled that the legislature's imposition of segregation was "reasonable," citing laws and lower court decisions from other states that supported his position. He deliberately ignored, however, the fact that nearly every northern state had Page 371 | Top of Article passed laws prohibiting racial segregation in schools and public accommodations. In response, Harlan criticized "reasonableness" as merely another name for a judge's personal values, agreed with Tourgee that the law was arbitrary, and predicted that the Plessy decision would stimulate racial hatred and conflict. Thus, the disagreements between Brown and Harlan turned more on facts and armchair social psychology than on precedent or public opinion. The terms of the argument between Brown and Harlan insured that the campaign of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to overturn Plessy, which led to Brown v. Board of Education (1954), would spotlight testimony by professional social psychologists and focus on social facts. BIBLIOGRAPHY Klarman, Michael J. "The Plessy Era." The Supreme Court Review (1998): 303–414. Lofgren, Charles A. The Plessy Case: A Legal-Historical Interpretation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. Thomas, Brook, ed. Plessy v. Ferguson: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford Books, 1997. J. Morgan Kousser See also Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ; Desegregation ; Segregation . Source Citation Kousser, J. Morgan. "Plessy v. Ferguson." Dictionary of American History. Ed. Stanley I. Kutler. 3rd ed. Vol. 6. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2003. 370-371. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 24 Aug. 2010. Document URL http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?&id=GALE%7CCX3401803290&v=2.1&u=txshracd2543&it=r &p=GVRL&sw=w Gale Document Number: GALE|CX3401803290