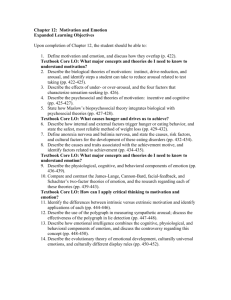

Implicit Theories of Emotion

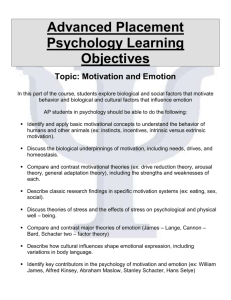

advertisement