THE ERIE DOCTRINE & McDONNELL DOUGLAS FRAMEWORK

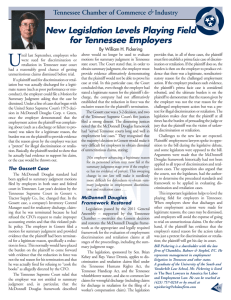

advertisement