the red and the black

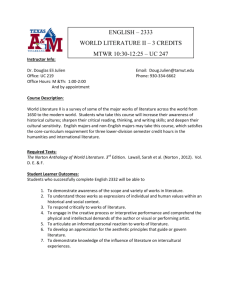

advertisement