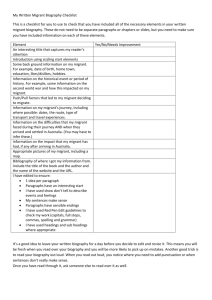

to read this Article - American University Law Review

advertisement