T he B acchae - Veritas Press

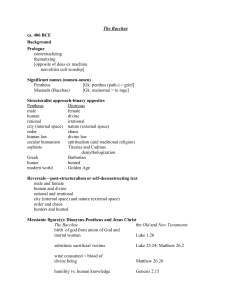

advertisement

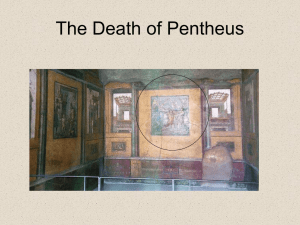

Th e B a c c h a e It is one of those moments when C.S. Lewis catches you off guard. It can’t be . . . but it is. Then you think, “What is he doing here?” Certainly it must be an invasion—new forces of destruction have been imported from ancient Greece to wreak some new havoc in Narnia. It seems the pagan god Bacchus or Dionysus has risen. He and his maenads are dancing around bringing who knows what sort of mischief to the forest. “Watch out Lucy! Watch out Susan!” you think. Where is Father Christmas when you need him? But wait . . . Bacchus . . . has come with someone. He is with Aslan! Didn’t see that coming! Lewis, however, the master storyteller has a point. He has imported this rascal and put him in the service of the Lion to show us how misguided our views of the faith often are. Sadly, modern Christians mistake the faith for something that would remove all joy from the world. They think Christ came to bring a sanitized, tightly controlled world where everyone would walk in lines and no one would play jazz. In that version of a Christian world sanctification would be evident by the length of one’s dour countenance. No one would climb trees. No one would pitch on the inside part of the plate. No one would spit or bleed or feast. Not so fast, says Lewis. The point of his use of Bacchus in service to Aslan is that a pharisaical world of mint, dill and cumin counting is not the world that God intended. Christianity replaces dour tasteless food with feasting. It replaces water with wine. It replaces minimalist silence and clashing cacophony with a symphony. It means to fill the world with laughter and joy. It will not stop until all of have been banished or joined the dance. 2 O m n i b u s IV Notice, however, that Lewis’s Bacchus brings freedom, but he is not free. His joy and laughter comes in the service of Aslan. Wine, finally, finds its place not as the purveyor of drunkenness, but as in the chalice of the Lord’s Supper. Euripides, however, is not a believer—not even close—and his Bacchus is not bound to Aslan. He is free, and with that freedom, he brings madness. General Information Author and Context Euripides (485–406 b.c.) was the youngest of the three great classical Greek tragedians. Roughly speaking, Aeschylus represents the conquering generation, Sophocles the conserving generation, and Euripides the collapsing generation of classical Athens. Born of “good family” he lived nearly his entire life in Salamis on a family estate, not far from Athens, until he was self-exiled to Macedonia in his last years. This may partially explain why he apparently was considered something of a loner for a public writer. It was said he wrote most of his plays in a cave by the sea. He was obviously familiar with the leading intellectual lights of his day, including Protagoras and Socrates, and acted as a lay priest in the sanctioned cult of Zeus. Euripides seems to have been an “edgier” writer, less “politically correct” than Aeschylus and Sophocles, and he was criticized during his lifetime for his innovations in tragic drama and his inclusion of “common people” in his plays. This may have been one reason why Euripides won only five first prizes (including one for The Bacchae) in the annual Athenian theatrical competitions, compared to twenty first-place awards for Sophocles and a dozen for Aeschylus. Apparently disturbed at the disintegration of classical Athens in his lifetime, he exiled himself to Macedonia where he lived the last few years of his life and wrote his final plays, including The Bacchae. Euripides intuitively sensed that the classical Greek city-state, based as it was on a formal Apollonian law and order, could not sustain peace and harmonious community any more than the old tribal societies, because the city-state failed to adequately address the need for Dionysian joy and freedom within their formal legal order. The setting of the play is the Greek city-state of Thebes in mythical times. The Dionysian takeover of Thebes was one of five famous mythological cycles of stories related to Thebes, which had the predominant mythological history of all city-states in ancient Greece. Euripides wrote the play near the end of the famous Peloponnesian War (431–404 b.c.), an ancient Greek military conflict, fought by the Greek city-state of Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League, which included Thebes and was led by the Greek city-state of Sparta. This is the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, when the Israelites first returned to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple after their exile in Babylon, then Persia. This would make Ezra and Nehemiah contemporaries of Euripides. Significance Euripides’ Bacchae is significant not merely because it is the last play written by Euripides and the classical Greek tragedians. The play itself questions the very worldview of the classical Greeks, and their attempt to control what they perceived to be fickle and inscrutable gods by rational organization and law. Euripides intuitively understood that the Greeks could not save themselves through the political device and organization known as the city-state. The Bacchae makes it clear that an imposed formal order based on the reason of man—whether of the individual through stoic self-control or of society through formal systems of government—cannot suppress sin, control our “irrational” impulses, or bring peace to a society. Such a solution will fail largely because it misunderstands the depths of humanity’s real problem. As a result, the rational imposition of law and order ironically creates the very same violence, chaos, and disorder it seeks to avoid by the suppression of nature, freedom, and change. The Bacchae unintentionally witnesses to the truth of Scripture’s view of mankind and society—man, individually or collectively—cannot save himself or keep himself “pure” by imposing rational law, because such systems merely cover over the real problem—man’s sin The Bacchae and his failure to love his Creator. Similar in some ways to the Pharisees’ strategy in New Testament Israel, the Greeks’ attempts to prevent sin and disorder amounted to “whitewashed tombs, which outwardly appear beautiful, but within are full of dead people’s bones and all uncleanness.” Inevitably, as Euripides understood, the impurity and dead bones of the classical Greek Main Characters Dionysus and Pentheus are the main characters in The Bacchae. Dionysus is the Greek god of wine and ecstasy, as well as a fertility god. He is son of Zeus and the human Semele. In the play Dionysus has two roles: the traditional god on high, and his disguised role as the “Stranger” who comes to Thebes to punish the Greek city for slandering his mother. Pentheus is the King of Thebes, son of Agaue, grandson of Cadmus and first cousin of Dionysus. Opposite in personality to his cousin, he is a law-and-order type, determined to keep control of Thebes by force if necessary. Despite his domineering, puritanical personality he is also a curious voyeur, secretly attracted to the Dionysian cult. Semele, mother of Dionysus and daughter of Cadmus, is already dead when the play begins. Cadmus is the legendary founder of Thebes. He is the grandfather of Penthius and Dionysus, and the only male public worshipper of Dionysus in his family. His friend and famous Theban seer (prophet) is Teiresias, who persuades Cadmus to worship Dionysus. Agaue is the daughter of Cadmus and mother of Pentheus. At the beginning of the play she is already one of the maenads (from the Greek mainad, “to be mad”), the secret cult worshippers of Dionysus, but her major role is near the end of the play. The Chorus represents female bacchants (followers of the secret Dionysian rites) from nearby Lydia, who are led by Dionysus in his disguised human form as the Stranger. Summary and Setting The Greek god of wine, Dionysus, appears on this pottery, which is an example of red-figure vase painting. This technique was developed in Athens in the sixth century b.c., and its greater flexibility in rendering detail soon supplanted the black-figure painting style which had dominated previously. city-states such as Athens were exposed by history. Euripides could not solve this vexing problem of humanity, but by pointing to the failure of the Greek solution he also unknowingly pointed to the truth of the gospel. Dionysus’ mother Semele was a princess in the royal Theban house of Cadmus. She has an affair with Zeus, becoming pregnant with Dionysus. Zeus’s jealous wife Hera tricks Semele into requesting Zeus to appear in divine form. Zeus’s appearance as a lightening bolt unfortunately burns Semele to a crisp. Zeus manages to rescue the unborn Dionysus stitching him into his “thigh” from which he is later born. (More appropriate chuckling!) Semele’s family maligns her name, does not believe her child was from Zeus, and rejects the young god Dionysus. As the action of the play begins, Dionysus returns to Thebes disguised as a human stranger, in order to vindicate his mother and punish the insolent city for refusing to acknowledge his divinity. In the meantime Cadmus’s proud and arrogant grandson Penthius has become King of the city, and promptly forbids the worship of Dionysus. Upon his arrival Dionysus first drives Semele’s sisters mad, and they promptly flee to the mountains to worship Dionysus. Though threatened by the Dionysian rites, Pentheus refuses to believe the women’s madness is divine and as- 3 4 O m n i b u s IV sumes they are purposely violating the orderly customs of Thebes. He orders his soldiers to arrest the stranger (Dionysus disguised) and his maenads. Dionysus permits himself to be arrested and taken back to Pentheus. Pentheus attempts to bind and torture the boyishly handsome stranger, without success. Attempting to tie up Dionysus, Pentheus finds he has only tied up a bull. Attempting to plunge a knife into Dionysus, he finds only the blade passing through the stranger like a shadow. Suddenly, an earthquake shakes the palace foundations starting a fire, and Pentheus is left dazed and confused. As Dionysus attempts unsuccessfully to persuade Pentheus that his path of resistance is destructive, a cowherd is brought before the King. The cowherd has witnessed a blissful scene of the maddened Theban women (including Pentheus’s mother) in the forest, alternately resting peacefully and feasting, singing and dancing, playing music and suckling wild animals. When, however, the women see the cowherd, they suddenly fly into a murderous rage and chase him within The Who, Janis Joplin, Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Santana, and Jimi Hendrix were among the performers at the infamous “3 Days of Peace & Music.” inches of his life. He barely escapes, and his poor cows are torn apart by the crazed women with their bare hands. Frightened but intrigued by the cowherd’s story, Penthius is about to order another military expedition to arrest the Bacchants, when Dionysus the stranger offers Pentheus a chance to see the maenads in person, but undercover. Unable to resist, Pentheus accepts the offer. Dressing himself in a wig and long skirts, Pentheus becomes an effeminate cross dresser—a vain, arrogant and lecherous parody of a man of authority. When Pentheus at first cannot get a clear view of the women, Dionysus miraculously places him in a treetop. Instantly the maenads spy Pentheus atop the tree, and Dionysus signals them to attack. Friends, I must here hide from your eyes the horror of what follows. Let us just say it involves lots of violence, a lion, a beheading, and lots of tears. Worldview You may have heard about the Sixties and an American phenomenon called the “Hippie” movement. The Hippie generation believed in “peace and love,” and a more “back to nature” lifestyle, reacting against “the establishment” and what it perceived to be the lifeless materialism, dead religion, corporate conventionalism, and militarism of modern American society. At the end of the 1960s, a host of confusing and frightening things were happening. The Vietnam War was escalating and dividing the country, while the nuclear arms race between the United States and Soviet Union accelerated, the civil rights movement was in its prime with much racial tension, NASA was sending the first men to the moon, the radical student movement was at its zenith on many college campuses, demanding changes in education and government, and rock concerts The Bacchae and festivals became a staple of the youth scene. The most famous rock festival in history was held over three days in August 1969 on a large farm near rural Woodstock, New York. Over half a million young people showed up (originally expecting 50,000, the promoters planned for 150,000); the facilities were not adequate to handle this many people. There were copious amounts of drugs consumed, the New York Thruway was shut down due to traffic jams, and it rained off and on during the festival. Yet miraculously there were no riots, murders or serious criminal incidents. A book extolling “Woodstock Nation” lauded the event, and it seemed the Hippie spirit of Woodstock might live up to its “peace and love” claims. More big rock festivals promoting peace and love were planned, and on December 6, 1969, just four months after Woodstock, the Altamont Free Concert was held at a raceway in central California and approximately 300,000 people attended. Unfortunately, the spirit of peace and love turned to a spirit of anger and violence. Numerous riots broke out, one of the big name bands refused to go on stage for fear of the violence, another performer was knocked unconscious following a fight on stage, one man was murdered by a Hell’s Angel gang member, and three others were killed by a hit and run driver. As soon as their set was over, the members of the headlining band, the Rolling Stones, ran off the stage and into their limousines, and police had to be called to restore order. The whole sordid concert scene was filmed, including the murder. It was the effective end of “Woodstock Nation,” and the innocence of the Hippie movement. The famous classic rock song by Don McLean entitled “American Pie” includes these lyrics reportedly written about the Altamont affair: Oh, and as I watched him on the stage my hands were clenched in fists of rage. No angel born in hell could break that Satan’s spell. The maenads in a frenzy attack Pentheus in this wall painting from the Casa dei Vettii in Pompeii, excavated in the 1890s. 5 6 O m n i b u s IV And as the flames climbed high into the night, to light the sacrificial rite I saw Satan laughing with delight the day the music died. Like the young concertgoers in the Hippie era, the Bacchants, worshippers of Dionysus, can suddenly change from peaceful nurturers of young animals to murderers who tear their sacrificial victims apart in ecstasy. At one level, The Bacchae is a story about not enough of and then too much of a good thing. Ultimately, at a much deeper level, it is a story that, however dimly, perceives a flaw in man’s nature so fundamental that no formal government structure, organization or set of laws can successfully suppress it. Dionysus’s mother Semele is slain by the grandeur of his father Zeus in this painting by Gustave Moreau (1826–1898). Although The Bacchae reflects the unbiblical classical Greek worldview, Euripides was able to perceive, however imperfectly, this fundamental flaw of man’s nature because of the times he experienced. Placing The Bacchae in its historical and literary context will better help us see this. You may remember from your last trip to the ancient world (Omnibus I) reading some wild and wacky plays called Oresteia (by Aeschylus) and The Theban Trilogy (by Sophocles). Oresteia, written at the height of Athens classical glory was all about the transition of Athens from a society based on the oikos (Greek for “household”), governed by household gods and the laws of blood vengeance, to a society based on the polis (Greek for “city-state”), governed by the Olympic gods (Zeus and company) and a republican rule of law. In the oikosbased society, the most sacred bond of community had been “blood” (family or tribal relations) but because of constant family feuds the newer polis-based society was organized around a sacred “contract” between citizens and elected rulers. Oresteia was a celebration of the triumph of the city-state over tribal organizations, a change that initially seemed to bring so much peace, prosperity, and greatness to classical Athens. The Theban Trilogy, written a generation later, as the dark clouds of the Peloponnesian War gathered over Athens, is set in Thebes, where the city-state’s peace and prosperity are threatened by a devastating plague. It turns out that the Theban king violated the sacred contract of the city-state by engaging in unintended but forbidden sexual relations with his mother. The only way to end the plague and save the city-state is to make a scapegoat of the king, exiling him outside the city-state forever. Although there was still hope that the city-state concept would be successful and bring lasting peace, Sophocles’ play implies that maintaining the purity of the city-state, which was necessary to avert disasters, would not be easy. Euripides’ Bacchae was written as the Peloponnesian War was drawing to its destructive end and Athens was about to lose its classical glory forever. As the translator of the play notes: For three generations, ever since the repulse of Persian power, many Greek states had tried in varying degrees to order their public life according to reason; autocracy had given place to [limited] assembly, debate and the vote. This change had been followed by a generation of war; it had led to a degree of organization which had taken from life much of its liberty and beauty and joy and given anxiety in return. The life of reason was proving a heavy strain. Dionysiac worship offered an escape from reason back to the simple The Bacchae joys of a mind and body surrendered to unity with nature. Euripides witnessed the impact of more draconian laws and the conflicts they engendered in Athenian society as the war dragged on. He also noticed that fear of violence from excessive Dionysian freedoms often led ironically to violent means to repress those very Dionysian freedoms. The Bacchae highlights a universal situation of man’s condition—the fractured nature of both individuals and communities, and the resulting contradictions in our nature. We are disordered and fearful creatures, as well as guilty and lost creatures, but we react in different ways to our situation based on our personalities, our culture and our experiences. Additionally, we tend to swing between extremes in responding to our plight. Looking about for a solution to our dilemma, we often choose to favor one part of our nature as superior to another part based on the false assumption that one aspect of our nature, or one aspect of creation, is more righteous or pure than another. In a futile attempt to save (and justify) ourselves, we then repress, by force of law or violence, the aspect of our nature we deem impure or unrighteous. The Greeks recognized this to some extent in their mythological gods, which were of course simply projections of their own human nature and culture. Hence Apollo and Dionysus represented two divergent tendencies of man’s nature—his desire for order and control of his environment through reason on one hand, and his desire to be one with nature and experience authentic joy and freedom on the other. Both gods, that is both tendencies, manifest themselves at different times in the same person or society. Because we are broken and fractured creatures, Apollo and Dionysus battle for control within each of us, as well as in society. Each “side” of our nature tends to fear and despise the other side. The main point of Euripides’ play is that societies and people who tend toward the law and order of Apollo ignore at their own peril the demand of the human spirit for Dionysian experience. Those who in the name of law and order suppress that demand in themselves or others, as Pentheus attempts to suppress his own desires as well as those of Thebes, become unwitting agents of the very disintegration and destruction they sought to avoid by rejecting the Dionysian spirit in the first place. Pentheus had decided to protect the Apollonian civilization of Thebes from the excesses and chaos of Dionysus by banning him completely from the city. He refused to acknowledge or worship the god and prohibited all Thebans from doing the same. His measures were in fact a mirror image of Dionysian excess, using excessive force under the guise of law and order to keep out what he feared most. Dionysus is not just the god of wine and revelry, but also of fertility. In the play the stranger turns into a bull—the ancient symbol of fertility—when Pentheus tries to tie him up. This is an apt image given that the futility of controlling Dionysus can be compared to the futility of riding a bull—the best bull riders in the world can only control the bull for a matter of seconds. As Euripides makes clear, the Dionysian bull is in fact impossible to control. Yet this is precisely what the Greeks were attempting to do in their fifth century b.c. city-state organizations. They considered their city-states as islands of law and order in a sea of chaotic nature. Thus, when Pentheus is forced to deal with Dionysus the stranger, who has led the maenads out to the wild mountain, he brings him inside the city of Thebes, hoping thereby to tame him through the civilization devices of the city. The Dionysian-inspired earthquake destroying Pentheus’s palace soon reveals that this strategy is hopeless and foreshadows the eventual takeover of the city by Dionysus himself. Pentheus’ refusal to acknowledge the divinity of Dionysus (that is the reality of the Dionysian side of the human spirit) is the height of folly because it is the denial of an undeniable fact. Pentheus had been warned: after reprimanding the old men, Cadmus and blind Teiresias, for participating in Bacchic rites, the blind prophet responds to Pentheus: “Power and eloquence in a headstrong man spell folly; such a man is a peril to the state…pay heed to my words. You rely on force; but it is not force that governs human affairs.” After Teiresias implores Pentheus to acknowledge the divinity of Dionysus, the Chorus chimes in, noting that worshipping Dionysus “shows no disrespect to Apollo.” Euripides thus implies that the Apollonian and Dionysian sides of man’s nature are not mutually exclusive, not an “either-or” proposition. Both sides of man’s nature need to be heeded. Yet other than implying this need, Euripides gives us no clue as to how the multiple aspects of man’s nature can come together. His is only a negative warning about the need to somehow have them come together. Christians also sometimes mistakenly assume that either the Apollonian or Dionysian side of our nature is “more Christian” than the other side. In so doing they fall into the trap of favoring certain aspects of nature and creation over others. Self-styled “conservative” Christians are especially prone to make the mistake of Pentheus, preferring an Apollonian law-and-order approach to life while trying to shut out other, Dionysian aspects of creation, such as creativity, wine, music, dance and theater. Because 7 8 O m n i B u s iV Bacchus is the Latin name of Dionysus. In his piece entitled Bacchus, Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652) imparts a somber tone to the revelries with his flat color palette and deep shadows they easily perceive the sinful perversions in Dionysian life, but fail to perceive the sinful perversions in their own Apollonian life, the Dionysian things are deemed too dangerous and are therefore banned. There are two tragic consequences of this unbiblical “Pentheus strategy.” First, the Christian life is stunted by the suppression of valid aspects of our nature and creation. As a result unbelievers end up controlling the Dionysian aspects of life in society by default. Second, as with Pentheus, walling ourselves off from aspects of creation is ultimately counter productive, and Christians who take such a strategy risk becoming, along with their children, victims of the very perversions they sought to suppress. At bottom, this “Christian” Pentheus strategy is a form of escapism and an unbiblical attempt at purification based on works rather than the imputed righteousness of Christ. The Bacchae also demonstrates the destructive nature of both Apollonian and Dionysian extremes in several contexts.2 For instance, Pentheus and Dionysus have conflicting and distorted definitions of wisdom and justice. Pentheus sees the rites and festivals of Dionysian worship as unwise, the very height of folly. By contrast, Dionysus considers Pentheus a fool for his refusal to acknowledge the Bacchus, the source of true wisdom. Similarly, Pentheus thinks that justice is established by maintaining order through the use of force. Dionysus, on the other hand, uses the term to describe the vindication of his mother through revenge against his enemies. The Bacchae Neither Pentheus nor Dionysus represent a biblical understanding of wisdom and justice. Biblical wisdom and justice are not possible without the redeeming of our minds through the power of Christ, in whom reside all the riches and treasures of wisdom. True wisdom does not consist in worshipping any aspect of man’s nature, Apollonian or Dionysian. Nor does true justice involve authoritarian force or savage human revenge. Euripides also gives us a glimpse of the conflicted nature of man in the double sidedness of Bacchic madness. The Bacchants are first described in peaceful harmony with nature, joyful in song and dance, making sweet music and nurturing young animals. Yet later they fly into a rage, savagely attack and tear apart the very same animals, dancing like whirling dervishes and destroying anything in their path. Although Euripides has insights into the contradictions and conflicts within human nature, he has no ability to point us to a resolution of those conflicts because of his unbiblical view of God and man’s relationship with God. He is a man of his place and time, and cannot see beyond the classical Greek worldview. He lives in a world controlled by inscrutable fate, where in fact nobody is in control, not even the gods. The gods seek to be acknowledged as superior to man and as an integral part of the universe, but are otherwise not interested in real relationships with man. The gods do not communicate any coherent revelation about reality to man, and are every bit as fickle, unpredictable, and unreliable as man is. As a result, man is at the mercy of the gods and cannot in any meaningful way be responsible for his problems. Yes, Pentheus failed to acknowledge Dionysus, yet in Euripides’ view his blindness is not so much moral (for the gods are amoral) as it is a defect ordained by the gods or fate. As a result Euripides cannot point us to a positive solution to the problem caused by the conflict of our Apollonian and Dionysian natures. The Greeks’ only recourse, implies The Bacchae, is to add more Dionysian festivals to the city-state, as an outlet for the Dionysian passions, and hope that excesses are kept to a minimum. This is at best a patchwork approach to a much deeper problem. It is also eerily similar to the modern American approach of working hard during the week (Apollonian style), then “doing-your-own-thing” on the weekend (Dionysian style) to counterbalance the grind of the week. It is sort of a balancing approach to our nature which, given the unpredictability of the gods and fate, gives little confidence or comfort, although our American “balance” consists of falling into the Apollonian ditch of excess for five days so that we can fall into the Dionysian ditch on the weekend—which is, of course, not getting a balance of anything. The biblical solution to the problem raised by Euripides goes to the root of the matter, and therefore is ultimately much more comforting to man. The world is not subject to the whims of fate but is under the direct control of the Triune God who loves us and ordains everything ultimately for our own good. No matter how messy the world may appear to us because of our sin and lack of comprehensive knowledge, we can trust in the Lord Jesus Christ precisely because of His sovereignty and character. He has communicated to us a coherent revelation of reality in His word and has given us His Spirit to guide us. In His word, He has revealed to us that it is neither anything in the creation nor any aspects or characteristics of our nature, whether Apollonian, Dionysian or otherwise, that are bad in themselves, but rather the sin that so easily besets us in all aspects of our character. Sin is our refusal to submit to our loving Creator in all areas of life. The only solution to sin is faith in the One who died for our sins and is in the process of redeeming us and the whole world. Submitting to Christ in society will heal the conflicts between Apollo and Dionysus, both within us and in our communities, thereby permitting all aspects of our nature (law and spirit, nature and civilization, freedom and responsibility, Apollo and Dionysus) to be redeemed and act harmoniously together, as God intends. Christians who really seek to be a part of God’s redeeming history must focus their efforts on transforming and bringing together the Apollonian and Dionysian aspects of life for the sake of the world and the glory of our Lord and Savior. —William S. Dawson For Further Reading Girard, Rene and Yvonee Freccero. The Scapegoat. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989. Kitto, H.D.F. Greek Tragedy. New York: Routledge, 2002. Leithart, Peter J. Heroes of the City of Man. Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 1999. Spielvogel, Jackson J. Western Civilization. Seventh Edition. Belmont, Calif.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2009. 78. 9 10 O m n i B u s iV sessiOn i: preluDe Question To Consider: Why do you think people sometimes feel like running away from home or school or work? Why do you think people sometimes feel trapped by “civilization” and just want to escape? Are these inclinations wrong ? From the General Information above answer the following questions: 1. In what time period and where did Euripides live? Who were the two other great Greek Tragedy playwrights? 2. The Bacchae unintentionally witnesses to what fundamental truth of Scripture? 3. What is the main point of Euripides’ play? 4. What were the classical Greeks attempting to do by organizing city-states in 5th century b.c.? 5. What trap do Christians fall into when they assume that either the Apollonian or Dionysian side of our nature is “more Christian” than the other side? 6. Why can’t Euripides offer any real solution to the Bacchanalian dilemma raised in The Bacchae? reaDinG assiGnmenT: The Bacchae, lines 1–493 in the play) and civilization (represented by Pentheus and Apollo in the play)? Cultural Analysis 1. How does modern Western culture deal with the Apollonian and Dionysian aspects of life in its social structures and customs? 2. Why can’t modern Western culture adequately integrate these two aspects of life? Biblical Analysis 1. How does the Bible portray the Apollonian and Dionysian aspects of life? (Ex. 7–12; 32; Eccles.) 2. What is the biblical solution to the Greek dilemma regarding Apollo and Dionysus? summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating what you have learned from the material above. Is it more important to be civilized or be natural? reaDinG assiGnmenT: The Bacchae, lines 494–841 sessiOn ii: DiscussiOn The Bacchae, lines 1–493 A Question to Consider What does it mean to be natural? Is it a good or bad thing to be natural? sessiOn iii: WOrlDVieW analYsis The Bacchae, lines 1–841 Discuss or list short answers to the following questions: Text Analysis 1. In the opening of the play how does the Bacchant chorus describe the “mystic” power of Dionysus and what are the attributes that the Chorus warns Thebes to reverence? 2. According to the Bacchant Chorus who is the “blest man” and what “spirit” is Dionysus said to embody? 3. What are some of the Bacchic rites that are encouraged by the Chorus for reverencing Dionysus in the mountains? 4. What does The Bacchae story imply about the Greek’s understanding of nature (represented by Dionysus Fill in the following Chart 1 for Apollo, Dionysus and the Bible’s view of each of the subjects or questions in the righthand column. reaDinG assiGnmenT: The Bacchae, lines 842–1392 The Bacchae Chart 1:. WORLDVIEW OF APOLLO AND DIONYSUS COMPARED WITH THE BIBLE A P OL L O God and the gods D ION Y SU S The gods are superior beings who guide humans who do what the gods want and punish those who don’t. The gods are in competition for the worship of men and societies, looking for their proper due. Man’s Problem He is too artificial and repressed by his reason and fear of disorder to live well. Salvation Worship and love your Creator and Savior Jesus the Christ with all your heart, soul, and mind, and love your neighbor as yourself. Fate or Predestination How can you stay out of trouble? Which is better: civilization or nature? What are justice and mercy? BIBLE Fate is inscrutable and even impacts the gods, therefore we can never be sure of anything but only hope for the best—chance is always a threat. Set up a very ordered, hierarchical system of self and societal government and avoid any change or emotional responses that may disrupt the order. Nature—it lets you be who you really are, and creates an authentic rather than an artificial, hypocritical society. Ultimate justice and mercy come together in the incarnation of Christ who delivered mercy to man while keeping the justice of the Father. 11 12 O m n i b u s IV Session IV: Recitation The Bacchae 1. Why did Dionysus turn Semele’s sisters mad? 2.Why do the maenads “catch wild snakes, nurse them and twine them round their hair”? 3.According to the prophet Teiresias, why are Cadmus and Teiresias the only Thebans who will dance to Dionysus early on? 4.When Pentheus first hears of “this astounding scandal” (the Bacchanalian activities) in his city, what does he claim he is going to do to the Bacchants and to the foreigner (Dionysus in disguise)? 5.What does the prophet Teiresias tell Pentheus about his plans to stop the Dionysian worship by force? 6.When Pentheus first puts the foreigner Dionysus in prison how does Dionysus respond? 7.What happened when the Bacchants, including Pentheus’s mother, saw the cowherd on the mountainside watching them? 8.What does Dionysus suggest and Pentheus agree to do so that he can spy on the female Bacchants? 9.Why did Pentheus’s mother not recognize him when he implored her to recognize him, as the women were about to tear him apart? 10.When Agaue returned to Thebes with the head of her son Pentheus, what did she think she was carrying? 11.Who brought Agaue to realize what she had done after killing her son? 12.Why has all this calamity happened, according to Cadmus? Session V: Discussion The Bacchae, Question To Consider: What is a “scapegoat”? Have you or anyone you know ever experienced being or been made into a scapegoat? Discuss or list short answers to the following questions: Text Analysis 1.Who controls Thebes when Dionysus first comes to town? 2.Who is responsible for leading the women of Thebes to worship Dionysus? 3.How does Pentheus end up being a “sacrifice” to Dionysus? 4.Who are the scapegoats in Thebes at the end of the play? Cultural Analysis 1.Do we have scapegoats in our society? If so, give some examples. 2.Rarely are our culture’s scapegoats physically exiled or killed. How are they made scapegoats in our culture? Biblical Analysis 1.What does the Bible say about the origins of the scapegoat in ancient Israel? (Lev. 16:8–26) 2.What is the relationship of Jesus Christ to the scapegoat? (Isa. 43:4; John 1:29; Heb. 9–10) The Bacchae Summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating what you have learned from the material above. Why is Pentheus an ineffective scapegoat, and why is Christ the only effective scapegoat in history? Optional Session: Current Events magazine, or in the newspaper that relates to the issue that you discussed today. Your task is to locate the article, give a copy of the article to your teacher or parent and provide some of your own worldview analysis to the article. Your analysis should demonstrate that you understand the issue, that you can clearly connect the story you found to the issue that you discussed today, and that you can provide a biblical critique of this issue in today’s context. Issue Assignment Identify Apollonian—or Dionysian—Worship in our culture today. Instead of a reading assignment you have a research assignment. Tomorrow’s session will be a Current Events session. Your assignment will be to find a story online, in a Current events sessions are meant to challenge you to connect what you are learning in Omnibus class to what is happening in the world around you today. After the The Triumph of Bacchus by Cornelis de Vos (1585–1651). 13 14 O m n i b u s IV last session, your assignment was to find a story online or in a magazine or newspaper relating to the issue above. Today you will share your article and your analysis with your teacher and classmates or parents and family. Your analysis should follow the format below: Brief Introductory Paragraph In this paragraph you will tell your classmates about the article that you found. Be sure to include where you found your article, who the author of your article is, and what your article is about. This brief paragraph of your presentation should begin like this: Hello, I am (name), and my current events article is (name of the article) which I found in (name of the web or published source)… Connection Paragraph In this paragraph you must demonstrate how your article is connected to the issue that you are studying. This paragraph should be short, and it should focus on clearly showing the connection between the book that you are reading and the current events article that you have found. This paragraph should begin with a sentence like I knew that my article was linked to our issue because… Christian Worldview Analysis In this section, you need to tell us how we should respond as believers to this issue today. This response should focus both on our thinking and on practical actions that we should take in light of this issue. As you list these steps, you should also tell us why we should think and act in the ways you recommend. This paragraph should begin with a sentence like As believers, we should think and act in the following ways in light of this issue and this article.