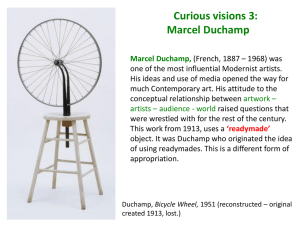

Marcel Duchamp and New Zealand Art, 1965-2007

advertisement