- Indiana State University

Policy Brief

2012-PB-02

April 2012

U.S. Insurer Operations and Regulatory Standard Developments in the Global

Market: A Timeline-based Examination

W. Jean Kwon

Abstract: Despite real premium growth rates, flattening per capital consumption of life and nonlife insurance and a downward move of the industry's contribution to the economy, the U.S. is still attractive to foreign insurance companies. At the same time, several U.S. companies continue or plan their operations in foreign soils. As a result, more governments improve their regulatory frameworks and work with each other to harmonize cross-border regulation for insurance market growth and stability regionally and globally. This paper examines the developmental status of the U.S. market during the past 30 years or so, developments of U.S. insurance regulation related to cross-border operations, and U.S.'s involvement in international regulatory and supervisory harmonization and standard-setting activities, including the Common

Framework for the Supervision of Internationally Active Insurance Groups (ComFrame), the

Multilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MMoU), regulation of Significantly Important

Financial Institutions (SIFIs) and international accounting standard-setting initiatives. It is recommended that the U.S. be more active in their participation while improving any unnecessary overlaps in the state-based regulation.

About the Author: W. Jean Kwon holds an MBA in risk management and insurance from

The College of Insurance in New York (now known as the School of Risk Management of St.

John’s University) and a Ph.D. in the same field from Georgia State University. He is a Chartered

Property Casualty Underwriter (CPCU). He taught insurance at Georgia State University and

Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. In Singapore, he also provided consulting services to insurance companies and organizations in the region and worked as Director of

Special Projects, Insurance Department, Monetary Authority of Singapore. In the United States, he worked as curriculum director at the American Institute for CPCU. He has authored several books, including Risk Management and Insurance: Perspectives in a Global Economy and Risk

Management and Insurance in Singapore. He currently teaches the School of Risk Management, continues to publish papers in academic and professional journals, presents research findings at various conferences, serves editorial boards of several journals, and advices multiple insurance institutions in the United States and abroad. He helped to establish Asia-Pacific Risk and

Insurance Association and organize World Risk and Insurance Economics Congress.

Keywords: Regulatory Efficiency, U.S. Insurance History, Market Performance, Regulatory

Harmonization, Globalization.

The views expressed are those of the individual author and do not necessarily reflect off icial positions of

Networks Financial Institute. Please address questions regarding content to W. Jean Kwon at kwonw@stjohns.edu

. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author. NFI policy briefs and other publications are available on NFI’s website ( www.isunetworks.org

). Click “Thought Leadership” and then

“Publications/Papers.”

P a g e | 2

I. Diversity in Financial Services Markets

In today’s dynamic financial services markets, capital and expertise flow through in nontraditional ways, market-specific distinctions continue to erode and few financial services markets remain local. Financial institutions increasingly intertwine existing products, invent intricate breeds and market them via innovative distribution channels. With the innovations in the markets, we expect improvement in productivity and lower intermediation costs. And, governments have increasingly promoted such innovations.

1

The innovations have also generated new risks and fed some old risks to become catastrophic, even travelling across economies at an ever-faster rate. Interconnectedness of economies, together with convergence across sectors in financial services, has exposed us to another layer of risk of cascading failure and runs, for example, contagion risk, which could stem from psychological fear as well. Presence of a new stream of information complexity is another byproduct (Chan-Liu, 2010).

Despite convergence moves in financial services and the introduction of laws promoting them around the world, we still find that diversity better describes financial services market operations.

Further, all parties of interest seem to agree that full integration of the services – pooling all financial services risks to one portfolio and operating the entire business with one capital and surplus – is unlikely to happen.

Specifically, the insurance sector produces contingent claims contracts to finance risks belonging to other entities. The underwriting processes are likely subject to greater problems of adverse selection and moral hazard than other types of financial services industries. The cost of insurance is not known a priori and claims experience can be volatile, especially in occurrence-based liability lines of business. Efficient management of risk portfolios (including pooling-diversification of the portfolios and risk repackaging via reinsurance and securitization) and capital flows

(including asset-liability management in duration and return) to minimize, if not prevent, any negative developments of the portfolios is critical in the insurance sector.

Depository institutions facilitate mainly the flow of money principally between (short-term) depositors and (long-term) users of funds. Their products and business models are comparatively diverse. The ability to manage a sustainable spread of interest rates and liquidity risk (e.g., longer duration of assets than that of liabilities) is one of the requisites for the institutions to stay financially and operationally sound. They are exposed to some underwriting risk but to a much lower degree as compared to insurance companies. Securities firms engage more in direct intermediation (between security issuers and investors) than in portfolio intermediation

(management of security portfolios), thus exposing them to counterparty risk as well. Both banking and investment firms can securitize and sell their asset and liability portfolios but do not have the equivalent of the reinsurance market for risk pooling or loss sharing, thus exposing them to the risk of cascading failures or runs.

1

For example, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Modernization Act of 1999 not only removed the last legal barriers between insurance, banking and investment industries but also authorized operations via a financial holding company. The act has triggered strategic alliances between insurance companies and banking institutions. The 2012 Michael White-Prudential Report finds that the top 12 bank holding companies (BHCs) garnered a record of $5.89 billion in insurance brokerage fee income during the first three quarters of 2011, a 14.4% increase from $5.14 billion for the same period in 2010 but lower than

$6.05 billion for the first half of 2009. The 2012 report also finds a total of 155 BHCs with at least $1 million in annualized insurance brokerage income. BHCs over $10 billion in assets continued to have the highest participation (89.0%) in insurance brokerage activities. Citigroup, Inc., Wells Fargo & Company (4.79%) and

Bancorpsouth, Inc. lead this segment, in terms of fee income. Nonetheless, the level of cross-sectoral integration and scope of integration seems to be stronger in other countries (e.g., France, Italy, Japan,

Korea, Malaysia and Singapore).

P a g e | 3

The operational and financial conditions of financial institutions have considerable spillover effects in the economy. Good economic regulation thus must reflect not only the commonalities but also the sectoral differentiae in risk composition and capital needs, not only between the sectoral markets but also within each sector.

We also observe supply of products and services by financial conglomerates. They have their own management issues (e.g., operational complexity and conflicts of interest between subsidiaries) and the economy has a new breed of public policy concerns, more with respect to the case of non-operational holding companies. A survey by the Institute of International Bankers

(2010) finds that existing policies vary across countries. The majority of countries, especially those large economies, permit financial services operations via financial conglomerates. Where permitted, the conglomerates often engage in joint banking and securities activities directly by the banking operation or via a subsidiary or affiliate. However, provision of both banking and insurance underwriting services by a single firm or a subsidiary of the conglomerate is prohibited in most jurisdictions – a policy reflecting the differences in core risks between these two markets.

Without a good system of financial integration and financial conglomerates – group-wise and at the subsidiary level – these developments could lead to another market failure.

Will the markets correct themselves to prove that Coase was right or will they need intervention of, say, government so that we enjoy quality, fairly priced products and services from reliable financial institutions? It seems the markets will not self-correct and the causes of market imperfections need to be manually controlled. An intervention by an independent and authoritative party (e.g., the policymaker and regulator) is thus called for.

2

Policymakers and regulators, individually and jointly, direct financial transactions and guide market conducts to protect the legitimate interests and rights of the less informed: consumers from lemon problems and agency problems; and suppliers from adverse selection and moral hazard problems. Market imperfections can also be caused by problems of market power. Private entities in a freer market may attempt to generate market power by differentiating their product and service quality, whereas those in a market with stringent product regulation may engage in monopolistic competition (e.g., a price war). In insurance markets, market power can also be facilitated by government actions. We find market entry barriers and exit constraints, particularly insurer bankruptcy regulation. Governments interfere with ongoing financial and operational matters of the regulated firms. Hence, governments need to find the right dose of regulation, as reduction in government intervention could alleviate some problems of market power. Be mindful, though, that an intervention is justified from economic and societal risk management perspectives

3

only when the policymakers and regulators are confident and the only reason for the intervention is to ameliorate the inefficiency or inequality.

4

Diversity also describes regulatory agency structures worldwide. Quite a few countries – from

Belgium to Nepal to Argentina to the U.S. – maintain a traditional sectoral agency structure for

2

Ironically, the mere presence of financial intermediaries evidences that the markets are with imperfections (e.g., information asymmetry) and, if left alone, the markets may fail to allocate resources optimally and fail to supply certain services, or supply them in some suboptimal way.

3

In this paper, economic regulation refers to the government control of a market with imperfections and social risk management deals with fairness and social justice. Two points are made here. First, market failures are not indictments of the capital market system and insolvency is an inevitable byproduct of the market. Second, the trend in social risk management is toward more stringent regulation in both developed and developing economies.

4

No intervention guarantees such amelioration and, retrospectively stating, the proper government response would have been no action even for inefficient markets, for instance, when the government fails to identify the causes of imperfection or when policymakers are captured by an interest group or seek economic rents from the regulated (White, 1996).

P a g e | 4 each of the insurance, banking and investment markets. This contrasts to the relatively recent single agency structures for the regulation of the entire financial services markets (e.g., the UK and Japan) or for more-than-one-but-not the entire markets (e.g., Australia and Peru). These single-roof structures could be effective in reducing the possible regulatory gaps and overlaps under the sectoral structures but could also expose the government to internal management issues that are similar in scope to the case of financial conglomerates in the private sector.

The government oversight in the markets is carried out commonly at the central government level except, for example, Canada and the U.S. (both in insurance regulation).

5

It has also been a norm moreso than an exception that a sectoral or cross-sectoral agency carries out the duties of protecting the rights of consumers as well as preserving reasonable profit-generating opportunities for producers. We witness a rise, albeit not as a fashion, in governments’ use of twin peaks approaches – in which one is responsible for policymaking and prudential concerns and the other for regulating antitrust and market conduct issues – as a means to minimize the problems arising from this duality in regulatory directions. In selected countries, the central bank or the securities commission is appointed as the prudential authority – a practice giving rise to another conflict resulting from possible interdependence between prudential regulation and national economic policies.

6

An alternative twin peaks approach would be establishing an agency exclusively for statutory and prudential matters (e.g., Korea with the Financial Services

Commission and the Financial Supervisory Service) and the UK ’s plan to dissect the Financial

Services Authority into the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority.

The Uni ted States’s creation of the Federal Insurance Office under the Dodd-Frank Act can be a similar approach.

Like in other financial services sectors, regulation in insurance covers broadly prudentiality, market conduct and antitrust standards. Prudentiality regulation promotes financial soundness of the regulated and corrects problems of information asymmetry and negative externalities. Riskbased regulation – Risk-Based Capital, Solvency II and stress test – is now supplemented by laws requiring broad disclosure of financials, strategies and corporate (enterprise) risk management progress to all stakeholders. A number of governments use sector-specific accounting standards – statutory accounting principle (SAP) or modified Generally Accepted

Accounting Principle (GAAP) – as a tool to minimize the impact of volatility of the liability side of the balance sheet from which major macro-risks stem (Eatwell, 2009) and to detect any hidden, potentially harmful, leverage.

Market conduct regulation is to capture inappropriate practices in the market systematically and to correct asymmetric information problems. Transparency in product design and pricing, supplier-consumer dispute management process, intermediary regulation (qualifications and conduct), among others, belong to this category of regulation. Using tools including but not limited to market entry barriers (e.g., business license requirement, minimum initial capitalization and, in some jurisdictions, fit-and-proper person regulation and application of economic needs test), market exit barriers (e.g., receivership and special bankruptcy law) and price-product control

(e.g., preapproval of new products or price change), governments attempt to prevent any unhealthy antitrust moves that could lessen competition in the market.

7

5

The U.S. states of Florida and New York now have a single agency for banking and insurance regulation.

6

The risk of similar regulatory conflicts of interest could also be observed in the countries in which the agency is part of the (de facto) central bank (e.g., Macau, Malaysia and Singapore).

7

Governments may create problems of market power by controlling access to or exit from a market. It is critical that a government maintains a precision balance between its consumer protection goals and fair market competition goals.

P a g e | 5

Supervisory and regulatory standards tend to advance along with economic development and with a rise of the domestic insurance industry’s contribution to the country’s economy. Generally, their insurance markets are competitive and governments focus more on operational and financial soundness issues in the market. Incumbent players – especially those in near-saturated markets

– may attempt to lessen the competition pressure by expanding business to new territories or product lines. The scope of regulation and supervision changes accordingly.

Governments should promote insurance market growth and stability, thereby preventing insolvency crises. When their markets are open to the entities from other jurisdictions or when domestic companies expand operations to other jurisdictions, they should prevent any adversities from cross-border operations to the consumers in their own jurisdictions. Harmonization of crossborder regulation is thus important for the growth and stability globally.

A number of intergovernmental entities have been created to help member countries coordinate their regulatory and supervisory policies. Yet, no intergovernmental agencies are known to be capable of directly coordinating the policies for the entire financial service markets internationally.

Instead, they tend to be sector-specific (e.g., the International Association of Insurance

Supervisors (IAIS) for insurance, the Basel Committee for banking and the International

Organisation of Securities Commissions for securities) or functioning as an additional layer for cross-sectoral work (e.g., the Financial Stability Board and the Joint Forum) or as a related organization sharing a common interest (e.g., the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the International Financial Reporting

Standard (IFRS). Their roles are examined later in this paper.

II. The Global Insurance Market and the United States

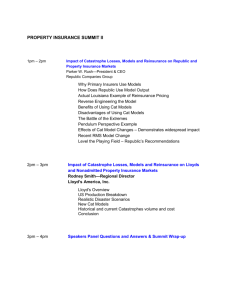

Figure 1A: Real Premium Growth (1980-2010)

Source: Swiss Re (2011)

Insurance is undoubtedly a necessity not only for the protection of life and wealth but also for economic growth. Numerous studies find evidence supporting a positive relationship between economic and insurance growth although we do not agree which one of the two causes the other.

The relationship seems to be stronger when an economy is in transition to a developing economy than it is to a developed economy or when a country relies heavily on exports for gross domestic product (GDP) generation. Figure 1A, for example, shows that emerging markets, many of them

P a g e | 6 being export-oriented economies, grew at a faster rate than industrialized countries during 1980-

2010.

Figure 1B: Nonlife Real Premium Growth (1980-2010) – Selected Countries

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

-20%

United States EU15 China India

Source: Swiss Re Database

Figure 1C: Life Real Premium Growth (1980-2010) – Selected Countries

80.0%

60.0%

40.0%

20.0%

0.0%

-20.0%

-40.0%

EU15 China India United States

Source: Swiss Re Database

P a g e | 7

Figures 1B and 1C highlight annual real growth rates of direct premiums in nonlife and life insurance, respectively, of the U.S., the inaugural 15 EU member countries (EU15), China and

India. We observe that the two developing economies often experienced higher, albeit more volatile, growth rates than the U.S. and EU15 in the nonlife market during 1980-2010. Similar observations can be made for the life insurance market during 1988-2010.

8

Figure 1B also shows that the U.S. nonlife insurance market experienced some growth during the liability crisis period (1984-1986), owing to a rise in liability insurance demand. Premium growth was also observed during the two years after the September 11, 2001 attacks (owing in part to a rise in property/liability insurance demand). In contrast, the growth rate remained flat or was even negative in most other years, including the years following the credit crisis, a phenomenon observed also in EU15. It seems the impact of the credit crisis was more strongly felt in the life insurance markets of the U.S. and EU15. The growth rate for 2010 was -0.2% for the U.S., as compared to 2.5% for the world.

Figure 2A: Nonlife Insurance Consumption (1980-2010)

$2,500

$2,000

$1,500

$1,000

$500

$0

United States

OECD

World

China

EU15

India

Figure 2A depicts changes in per capita insurance consumption (total premiums ÷ population) in

U.S. dollars for selected regions and countries during the past 30 years for the nonlife and life markets, respectively. We find that the U.S., despite continuous depreciation of the U.S. dollar against a basket of other hard currencies, continues to hold a leading position in the nonlife market. However, a further examination (not shown in this paper) of the consumption pattern by country shows that the U.S. led the world only until the early 1990s and Switzerland took over the leading position thereafter.

9

8

The 1980-1097 period is not included in Figure 1C because of extreme volatility of real premium growth rates for China ranging from 105.5% to 600.7%.

9

The Netherlands shows a leading position from 2006 but is not considered for this analysis because of a sudden and significant rise in per capita premiums from the period prior to 2006.

P a g e | 8

Figure 2B: Life Insurance Consumption (1980-2010)

$3,000

$2,500

$2,000

$1,500

$1,000

$500

$0

United States

World

China

EU15

India

OECD

Figure 2B shows that changes in per capita consumption of life insurance during the same period and the U.S. again led the world as compared to the average of EU15 or Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. A country-specific examination of the changes, however, indicates that the consumption was greater in Switzerland, Japan and

Finland than in the U.S. for most years in the 1980s. The UK began to consume more life insurance per capita from the 1990s and Ireland and Finland joined the leading group in the

2000s. The U.S ranked 15 th

in 2005 and 17 th

in 2010. The leading countries as of yearend 2010 include a number of Western European countries, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan.

Figure 3A: Insurance Penetration Ratios (Nonlife; 1980-2010)

P a g e | 9

6%

5%

4%

3%

2%

1%

0%

United States

OECD

World

China

Figure 3B: Insurance Penetration Ratios (Life; 1980-2010)

8%

6%

4%

2%

0%

EU15

India

United States

OECD

World

China

EU15

India

Figures 3A and 3B presents changes in insurance penetration ratios (total premiums ÷ GDP) for the same observations and period for nonlife and life insurance, respectively. We find that the

U.S. was leading th e world with respect to the nonlife insurance industry’s contribution to GDP but was not when it comes to life insurance contribution to the domestic economy. In 2010, for example, the U.S. ranked 21st for life insurance penetration ratio.

The U.S. insurance industry with about 2.238 million jobs (annual average) represents 2.1% of the national employment in 2010 (Insurance Information Institute, 2012). The total number of jobs is not much different from the number in 2001. However, a closer examination of the industry, however, shows that during 2001-2010 the number of jobs:

Increased from 597,900 to 638,300 (6.75%) in the insurance agency and brokerage segment;

P a g e | 10

Increased from 205,300 to 232,200 (13.1%) in other ancillary segments;

10

Decreased from 591,300 to 533,100 (-9.84%) in the direct nonlife insurer segment;

Remained almost flat around 807,300 in the direct life insurer segment; and

Decreased from 31,400 to 27,100 (-13.69%) in the reinsurer segment.

The reduction in the number can be explained in part by a series of mergers and acquisitions during the period. Using Conning & Company data, the Insurance Information Institute (2012) reports a total of 495 transactions with an aggregate transaction value of $106.833 billion in the property/casualty market during 2001-2010. It reports 216 transactions with an aggregate value of

119.086 billion for the life/annuity insurance industry, as well as 230 transactions with an aggregate value of 66.565 billion for the health insurance industry during the same period. New companies were also incorporated and some existing companies went bankrupt during the period. Insurer bankruptcy, however, seems not to be a major factor leading to the reduction in the number. To the contrary and as shown in Figure 4, the bankruptcy risk seems to be getting smaller in the U.S. property/casualty insurance industry during recent years (e.g., 11 impairments in 2010).

Figure 4: U.S. Property/Casualty Insurer Impairments (1969-2010)

Source: A.M. Best and the Insurance Information Institute

The changes in the employment portfolio are certainly affected by multiple factors, such as outsourcing claims, investment and other services to third parties, improvement in information technology and fewer U.S. domiciliary reinsurance companies today. As summarized in Table 1, the number of domiciliary direct insurance companies in the U.S. has also decreased. The reduction was faster in the life/health market (from 1,549 to 1,061 or 31.5%) than in the property/casualty market (from 2,800 to 2,658 or 4.4%) during 2000-2010.

Statewide variations nonetheless exist. In the property/casualty market, for instance, a significant reduction (e.g., more than 25%) in the number of incorporated companies is observed in: Alaska

(from 7 companies to 5 companies), California (from 159 to 117), Colorado (from 35 to 19),

Hawaii (from 33 to 18), Nebraska (from 43 to 30), Oklahoma (from 55 to 35) and Tennessee

10

Included in this segment are claims adjusters, third-party administrators of insurance funds and other service personnel such as advisory and insurance ratemaking services.

P a g e | 11

(from 34 to 19). During the same period, the number of insurance companies increased by more than 25% in: Maine (from 14 to 18), Massachusetts (from 18 to 54), Nevada (from 6 to 13), New

Hampshire (from 35 to 46), New Mexico (from 1 to 11), North Carolina (from 52 to 68) and West

Virginia (from 4 to 17). In the life/health market, most states experienced a relatively significant reduction (e.g., more than 25%).

Several states remain less attractive than others as a domiciliary jurisdiction for insurance companies. For example, no life/health insurance companies were reported to claim Alaska, West

Virginia or Wyoming a domiciliary state in 2010. Although not empirically supported, these variations imply possible differences in regulatory efficiency/competency, on top of economic and other external environmental factors, at the state level.

During 2001-2010, the life/health insurance industry also managed to generate net income in all years except 2008. During the same period, the U.S. property/casualty industry experienced a peak in premium income in 2006, followed by a three-year decline due in part to economic recession and in part to the credit crisis. The combined ratio after policyholder’s dividends was ranging from 116.6% in 2001 to 95.5% in 2007 and the annual return (net income after taxes) on equity remained positive in all years except 2001 in both SAP and GAAP bases in the property/casualty industry. In 2010, the property/casualty industry and the life/health insurance industry recorded a net gain of $37.387 billion and $53.1 billion, respectively, to surplus.

Table 1: The Number of Incorporated Companies by State (2000 vs. 2010)

State

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

D.C.

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

Property/Casualty

Year 2000 Year 2010

24

7

54

12

20

5

51

12

159

35

73

87

8

105

39

33

12

117

19

71

91

6

130

34

18

9

49

18

70

54

17

62

4

43

204

79

59

32

10

35

14

6

35

76

1

37

54

74

41

15

50

4

30

193

77

61

27

8

32

18

13

46

68

11

Life/Health

Year 2000

14

0

328

41

33

14

32

46

4

25

21

5

6

13

56

19

18

35

42

3

27

83

49

33

14

11

65

3

3

6

8

0

6

14

25

11

19

29

2

33

58

31

26

11

7

45

1

4

2

9

2

Year 2010

7

0

190

30

15

10

28

30

3

11

16

4

1

P a g e | 12

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont*

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

222

52

17

131

55

16

210

20

26

16

34

245

15

377

18

26

4

197

68

17

139

35

13

189

24

22

17

19

225

13

15

18

20

17

103

8

4

46

29

3

37

5

14

2

20

181

17

2

15

13

2

Wisconsin

Wyoming

175

2

180

3

28

0

22

0

Total ** 2,800 2,658 1,586

Source: Insurance Factbook 2011 and Financial Services Factbook (2003)

1,094

* The total excludes all U.S. territories and possessions. For the property/casualty, the total excludes Vermont which was recorded to have 377 and 15 for the number of incorporated companies in 2000 and 2010, respectively.

81

5

3

39

26

4

30

4

10

2

13

136

16

2

11

10

0

The combining effect of a rise in surplus and relatively weak growth in premium income results in probably “underwriting overcapacity” in the U.S. market. The following two graphs support this contention. Figure 5 depicts c hanges in policyholder’s surplus in the property/casualty insurance industry during 2005-2010. Figure 6 illustrates changes in the written premiums to surplus ratio of the property/casualty industry during 1970-2010.

Figure 5: Policyholders Surplus in the U.S. Property/Casualty Insurance Industry

(2005-2010)

Source: III, ISO and A.M. Best

P a g e | 13

Figure 6: Changes in the Premiums Written to Surplus Ratio in the U.S. Property/Casualty

Industry (1970-2010)

We observe no drastic changes in premium share by line in the U.S. property/casualty insurance market. In 2001, the market wrote 39.5% of net premiums in private passenger automobile insurance (inclusive of 23.1% for liability coverage), 6.7% in commercial automobile insurance

(inclusive of 4.7% for liabi lity coverage), 10.9% in homeowner’s insurance, 8.8% from workers’ compensation insurance and 6.1% in other liability insurance (Insurance Information Institute,

2003).

11

In 2010, the market generated 37.6%, 5.0%, 14.4%, 7.4% and 8.4%, respectively, from the lines of business (Insurance Information Institute, 2012). During the same period, the shares of specialty lines did not move much, for example: products liability (from 0.6% in 2001 to 0.5% in

2010) and medical malpractice (from 1.9% to 2.1%). The share for reinsurance even shrank significantly from 3.9% to 2.9% during the period.

The focus on the domestic market operations by U.S. insurers and the attractiveness of the market by foreign firms result in insurance trade deficit for the U.S. Figure 7 shows that exports, imports and trade balance of private services in 2009-2010. Payne and Yu (2011) report that the largest U.S. trade surplus is financial services ($42.2 billion) and the largest trade deficit is insurance ($41.9 billion) in 2010.

12

From Table 2 for gross reinsurance premiums assumed/ceded, we find that North America is a net importer of reinsurance and Europe the only net exporter.

Figure 7: Exports and Imports of Private Service

11

Other liability insurance includes but is not limited to contingent liability, errors and omissions, environmental pollution and umbrella and liquor liability insurance.

12 It is not clear whether U.S. corporations’ and insurance companies’ purchase of insurance in

Bermuda and the Caribbean was treated as export by the authors.

P a g e | 14

Source: Payne and Yu (2011)

Table 2: Assumption and Cession of Reinsurance by Region (2009)

Europe

North America

Asia and Australia

Africa, Near and Middle East

Gross Premiums

Assumed

97,268

63,927

2,201

--

Latin America --

Source: Global Reinsurance Market Report (IAIS, 2011)

Ceded

(60,143)

(72,941)

(14,569)

(3,419)

(5,825)

Net Position

37,125

(9,014)

(12,368)

(3,419)

(5,825)

The U.S. insurance market is certainly developed and competitive. The sheer size of the market

(e.g., premium revenue in the property-casualty market) is attractive to foreign insurance and reinsurance companies. The market is known for a web of multifarious, state-based insurance regulatory systems, thereby making it challenging and costly for the companies to comply with regulatory guidelines (e.g., filing of insurance business application forms and premium rates).

We find attractive insurance markets in other countries and regions. The EU is certainly attractive.

So are emerging economies. China and India, for example, still contribute relatively small to the global insurance market (see Figures 2A and 2B) but their insurance markets are fast becoming an important part of the domestic economy. As depicted in Figure 3B, the contribution of the life insurance market to the economy in 2010 was greater in India (4.44%) than in the U.S. (3.46%).

P a g e | 15

Swiss Re (2012) reports that both China and India led the growth of Asian emerging markets. It also reports that the common denominators of the success of the markets include:

A sound economic environment including lower inflation in most emerging Asian and

Latin American countries;

Improvement in insurance supervision, the introduction of insurance-enabling regulations, and further market liberalization to enhance competition and productivity;

Product innovation, including takaful, microinsurance and index-based weather insurance for agriculture; and

The use of multiple distribution channels to reach a broader population spectrum, in particular the successful leveraging of bancassurance.

Accordingly, several U.S. insurance groups have been operating in foreign soils as well. We note some notable cases here.

The American International Group (AIG) underwrites life and nonlife risks internationally.

Their major nonlife business lines were personal, accident & health, energy, liability and other specialties. For the reporting year of 2006 – then with the American International

Assurance Company, the American International Underwriters, Direct Brokerage Group,

Transatlantic Holdings and United Guaranty Corporation – the share of premiums written internationally was 31.45% ($17.7 out of $52.28 billion) for nonlife insurance and 65.2%

($43.4 out of $66.59 billion) for life and annuity insurance.

The Hartford Financial Services Group underwrites life, annuity and investment-linked risks mainly in Japan, Brazil, Ireland and the UK. The group reports no international operations in nonlife insurance, and the revenue from international operations remains small at the group level.

The Travelers Companies has operating arms in Canada, Ireland and the UK (including participation at the Lloyd’s of London). The group is mainly in nonlife lines of insurance business outside the U.S. The group generated 5.6% of direct written premiums from international operations for the reporting year of 2010.

The Liberty Mutual Group provides coverages in personal and small business lines as well as reinsurance services via its Liberty International Underwriters. It operates in Latin

America (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile and Venezuela), Europe (e.g., Ireland,

Poland, Portugal, Spain and Turkey) and Asia (China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam). It reports $8.566 billion of revenues in 2011 by the company’s International

Business Unit. This represents 24.9% of the group’s total revenue for the year.

The Chubb Corporation began its operation in Europe (using Chubb Insurance Company of Europe incorporated in Belgium in 1962), Australia in 2006, Brazil in 1973, China

(initially via a branch of the Federal Insurance Company in Hong Kong in 1984), India in

2002, Korea and Taiwan. Chubb Insurance Company of Canada offers niche market services in personal and business lines. The group reports in its 10-K for the year of 2010 that 24.69% ($3.16 out of $12.81 billion) of premium revenues was international.

A few other U.S. companies have made foreign direct investments but their premium revenues from international operations are probably insignificant for most of them. In contrast, leading

European insurance companies commonly operate internationally. For example, Skipper and

Kwon (2008) find that, in 2006:

P a g e | 16

Allianz Sach (Germany) generated 24.7% (or €11.4 out of €46.2 billion) of nonlife premium income from its home country and 9.65% from the U.S.

Zurich Financial Services (Switzerland) wrote premiums amounting to $7.13 billion

(21.07% of the total premiums) and $11.9 billion (33.88%) from global corporate and

North American operations, respectively.

European companies – Munich Re, Swiss Re, Hanover Re, SCOR, Allianz and Lloyd’s – continue to be strong in the global reinsurance market. In 2010, the Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance

Group, after completing a retroactive reinsurance deal with CAN and a life reinsurance deal with

Swiss Re Life & Health (America), was the only U.S. reinsurer in the top 10 list by A.M. Best.

13

Today’s U.S. insurance market can be characterized by low real growth rates of direct premiums, flattening per capital consumption of life and nonlife insurance and a downward move of the industry’s contribution to the economy.

14

The economic pie of the global insurance market continues to grow but the share for the U.S. gets smaller. The underwriting capacity of the U.S. market builds up. There will be no drastic changes in demand and the impact of a gigantic natural or man-made disaster or another economic crisis would be of short-term. The U.S. market is in need of new momentum to step forward from the status quo.

III. Coordination of Insurance Regulatory and Supervisory Standards

The global trend is toward placing greater reliance on competitive insurance markets. However, this does not mean that the markets will be completely private-sector driven. Governments commonly underwrite societal economic security-related risks, for instance, in public pension, national healthcare and workers’ compensation insurance markets. Governments may also provide coverages in the areas where the private insurance mechanism fails to respond adequately to a perceived need for insurance. Accordingly, the U.S. government supplies several insurance programs including but not limited to: Social Security programs (OASDHI), flood insurance, crop insurance, inner-city crime insurance, and life insurance and annuity for government and military personnel. The government may return one or more of the programs to the private sector when the market has (re)built capacity in the future.

Fast growth of an insurance market does not necessarily translate into making the market financially or operationally healthy. Typical insurance authorities would prefer a market in which all carriers manage gradual, long-term growth – even when an insurer possesses managerialtechnical expertise and sufficient capital surplus, ceteris paribus . They would not welcome any insurers attempting to generate excessive financial leveraging as they are already in the business of debt instrument issuance (i.e., future insurance coverage obligations). The authorities recommend insurance companies to be conservative in investment as well as to match their assets with liabilities for duration and return. Insurance regulators commonly apply a bankruptcy

13

Other U.S. reinsurers in the top 25 include Everest Re, Reinsurance Group of America, Transaltantic

Re and OdysseyRe.

14

Skipper and Kwon (2007) note that the U.S. life insurance industry faces competition with other financial institutions (especially with the introduction of the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act), pressures to strengthen corporate risk management (as in part per Risk-

Based Capital (RBC) regulation) and regulators’ push for stronger financial monitoring (now with the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act). They also note that the imposition of RBC requirements has not been kind to small insurers (thus leading to market consolidation), dynamics in tort reform (leading to a lack of precision in insurers’ establishing loss reserves in long-tail liability lines) and underwriting catastrophic risks are some of the critical issues in the U.S. property/casualty insurance industry.

P a g e | 17 principle in lieu of an ongoing principle for financial examination of the regulated. In a number of countries, insurance companies are required to submit statutory accounting principle-based financial statements, thus recording smaller total assets than in GAAP-based statements.

Increased reliance on and nurturing of a competitive market requires that the government do away with a rule-based regulatory framework and create a principle-based, ex post supervisory environment. The regulatory authorities then rely more on financial data and statistical tools for better monitoring of market activities and for better evaluation of risk and capital of the regulated companies. They use the findings – along with other key findings – to establish new policies and to amend existing ones.

Governments analyze the data to understand more about the markets under own jurisdiction vis-

à-vis the markets under other jurisdictions. They do so, on the one hand, to make their own domestic markets more attractive than others ’ and, on the other, to help their own domiciliary companies expand business to other jurisdictions without being subject to any unfair treatment by the host country authorities. Governments compete with each other – for a good cause in most cases – and more insurance markets are becoming regional and global.

15

The fear is that not all governments would invest for regulatory improvement and some lack the resources, thus becoming a regulatory black hole.

Regionalization and globalization makes sense when the participating economies and companies benefit from positive scale/scope or comparative economic effects from doing business in a foreign soil or cross border. It is a matter of fair trade between economies. It is an issue of regulatory harmonization at the intergovernmental level for the protection of consumers from the failure of foreign companies in the domestic market as well as from the failure of domestic companies’ operation in foreign soils.

The U.S. is known for its advanced regulatory framework and reliance more on ex post approaches. For years, all U.S. state regulators have agreed to use National Association of

Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Statement Blanks and the NAIC Financial Data Repository

(FDR). This uniformity in data collection and warehousing lets us quantitatively evaluate several regulatory and supervisory issues. For example, we can easily estimate Incurred-but-not-reported

(IBNR) and other loss developments using Schedule P data and calculate “Funds Held by

Company under Reinsurance Treaties, ” statutory penalties for unauthorized and overdue reinsurance, using Schedule F-Part 3 information. Using the Schedule D data from the NAIC FDR

(e.g., investment in mortgage/asset-backed securities in non-U.S. sovereign and local governments), we could measure in detail the U.S. insurance industry’s exposure to each of the

EU member countries.

Recognizing the value of U.S. prudential regulatory approaches, several foreign authorities have applied the U.S. approaches, albeit with modification, to monitor insurer financials in their domestic markets. The Insurance Regulatory Information System (IRIS), part of NAIC’s Financial

Analysis Solvency Tools (FAST), is one still used by non-U.S. authorities. The U.S. RBC framework is the foundation for localized risk-capital regulations in several countries outside the

U.S.

Developing economies as well as countries with a small domestic insurance market have also found it worth borrowing similar techniques developed by other economies. Examples include a

Canadian approach to monitor foreign insurer operations in Canada using not only the financials of the foreign companies but also their holding companies headquartered outside Canada. The

UK solvency margin approach is still ubiquitous around the world, especially in Commonwealth

15

Refer to IAIS (2011) for a discussion of issues related to cross-border insurance transactions by insurance groups and single insurance companies as well as in reinsurance.

P a g e | 18 member states.

16

The EU is now promoting Solvency II to control risk management activities not only by EU insurers in and outside the region but also by non-EU insurers operating in the EU market. By promoting the locally developed standards in the regional and global markets, these governments expect that their domestic markets are serviced by confident – operationally and financially sound – insurance companies and that their domestic insurers face less foreign regulatory environments for operations outside their domiciliary jurisdictions.

If one aspect of prudential regulation must be singled out as the most critical, it surely would be an insurer's net worth (capital and surplus) positi on relative to the insurer’s risk portfolios. A wide array of approaches in this ongoing capital and solvency regulation are observed around the world. In a number of countries, particularly those with an insurance market that is relatively less developed, does not contribute much to the local economy or both, the minimum ongoing capital and surplus requirements are set out as fixed ratios of surplus to premiums written and to claims incurred (nonlife) or mathematical reserves (life insurance).

This fixed ratio approach fails to consider other explicit enterprise-wide risks inherent in insurance operations. To correct the problems in this approach, retrospectively termed as Solvency I, the

EU has developed Solvency II. This modified approach relies on risk management-based supervision akin to that adopted for banks via the Basel II requirements. Solvency II is certainly adaptive to changes in the internal and external environments that surround insurer operations but not completely. Like RBC regulations, the Solvency II regulation focuses on the risk-capital relationship of the regulated, inclusive of the regulation at the level of insurance groups in this EU approach.

Representing the EU, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) seeks greater harmonization and coherent application of rules for financial institutions and markets across the EU, strengthens oversight of cross-border groups and promotes coordinated

EU supervisory response, among others. The EIOPA is responsible for implementation and administration of Solvency II.

To be effective in January 2013, Solvency II addresses systemic risk and group risk in commercial insurance markets of a country and across countries. The U.S., represented by the

NAIC, is in search of a solution to U.S. equivalence for Solvency II but was not included in the

February 2012 list of the countries for Solvency II equivalence.

This year, the EIOPA plans to set the criteria for the evaluation of “third, non-EU” countries. Third countries can seek equivalence in reinsurance, group supervision and group solvency. For example, reinsurers from equivalent countries would not be subject to collateral requirements in

Europe.

The U.S. federal Nonadmitted and Reinsurance Reform Act (NRRA; effective on July 21, 2011) requires a U.S. state to recognize credit for reinsurance if the domiciliary U.S. state of the ceding company recognizes the credit and is an NAIC-accredited state (or equivalent).

17

Despite the improvement in foreign companies access to the U.S. market, foreign governments and entities may argue that the state-based license requirement remains as a barrier to a more efficient

16

This approach was first introduced in the UK in 1946.

17

Foreign governments and entities ask U.S. state governments for a more favorable treatment of the reserves (i.e., the statutory penalties of 100% of the premium) for unauthorized reinsurance. The NAIC finally passed in November 2011 amendments to the Credit for Reinsurance Model Act and Regulation. The model act allows even a zeropercent collateral for reinsurers with a “Secure-1” rating by the state’s insurance commissioner, A++ Best’s Financial Strength Rating or AAA/Aaa Financial Strength Ratings by

S&P/Moody’s (Sidley Austin, 2012).

P a g e | 19 access to the U.S.

18

Further, it remains to be seen what role the Federal Insurance Office (FIO) will play if it attempts to set a market access policy at the federal level. The FIO identifies itself as

“not a regulator or supervisor.” Separately, the NAIC identifies itself as the “standard-setting and regulatory support organization ” governed by chief U.S. insurance regulators.

19

The EIOPA and the NAIC seem to share a number of common goals. However, a major difference exists between these two entities: the EIPOA is a “fully-fledged” official European agency, whereas the NAIC is not an official part of the federal or state governments. Accordingly, the EIOPA has expressed a concern that the U.S. maintains state regulation and the NAIC is n either “supervisory authority in its own right” nor a “competent authority.”

Obviously, cross border harmonization of regulatory and supervisory frameworks would be desirable in global markets. International coordination and cooperation in insurance supervision and regulation thus continues and intensifies as more economies develop. We summarize selected key developments in this section.

First, the IAIS has proposed several models for multinational supervision. We summarize three of them – Insurance Core Principles (ICPs), the ComFrame and the MMoU.

The IAIS revised the (ICPs in 2012. The ICPs cover the key aspects of insurance supervision including the structure of the supervisory authority, licensing, off-site analysis, on-site inspections, solvency, governance, market conduct and financial stability. The principles are supported by standard and guidance materials developed by the IAIS. The

IAIS relates the ICPs to the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) by the IMF and the World Bank.

The MMoU (introduced in February 2007) sets the minimum cross border supervision standards to which signatories must adhere. The IAIS reports 22 signatories including the only one from the U.S., the Connecticut Insurance Department (February 20, 2012).

20

Finally, the ComFrame is for macro-prudential supervision (i.e., group-wise supervision) and is part of the IAIS’ response to the credit crisis and the continuous evolution of the insurance industry.

21

For example, many global insurers and reinsurers reported significant losses as a combined result of their non-insurance activities and the inefficiency of corporate governance and risk management. In their view, regulation was too much focused on micro-prudential regulation (i.e., at the individual firm level), as opposed to macro-level considerations. There was a lack of coordination of responsibilities between supervisors as well as a lack of efficient tools to minimize regulatory arbitrage across borders and sectors. ComFrame does not directly address systemic risk but it does address: the business structure, business mix and business development of the group from the perspective of risk management; quantitative and qualitative requirements; and supervisory cooperation and interaction.

18

It should be noted here that it is not a perfect national treatment principle issue, as the unauthorized insurance regulation applies to reinsurance ceded to other U.S. states and abroad.

19

At its homepage, the NAIC now self-identifies as a “standard-setting regulatory support organization” as compared to previously a “voluntary organization.”

20

The summary report for the NAIC International Regulatory Cooperation (G) Working Group meeting on Ma rch 2, 2012, notes that the group “…also learned of [Connecticut’s] recent acceptance to the MMoU.”

21

Fortune Global 500 (2008) lists 27 U.S. insurance groups in life and 18 in nonlife. The life group includes MetLife, New York Life, TIAA-CREF, Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance, Northwestern Mutual and Prudential Financial. The nonlife includes Berkshire Hathaway, AIG, Allstate, Traveler’s Insurance,

Liberty Mutual, Hartford Financial Services, Nationwide, Loews and State Farm.

P a g e | 20

The ComFrame is proposed to include 5 Modules, Scope of Application, Group Structure

& Business, Quantitative and Qualitative Requirements, Supervisory Cooperation &

Interaction and Jurisdictional Matters, for the group-wide supervision of the Internationally

Active Insurance Groups (IAIGs). The NAIC supports this project while noting that U.S. experience from managing the multijurisdictional system of regulation could have a strong influence on the multijurisdictional system (Vaughan, 2011).

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) develops and promotes the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies. For this, the FSB manages the work of national financial authorities and international standard setting bodies on an international scale. In

2011, it published a consultative document dealing with systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs), “the financial institutions whose distress or disorderly failure, because of their size, complexity and systemic interconnectedness, would cause significant disruption to the wider financial system and economic activity ” (FSB, 2011).

22

Implementation of the measures begins in

2012 and the full implementation is targeted for 2019. Differences in the definition of systemic risk

(the Geneva Association, 2011) as well as the classification of SIFIs in insurance and other financial services sectors exist.

Table 3: Working Relationship of Intergovernmental Agencies (Selected)

The IMF, the World Bank, the Joint Forum, the OECD, the IASB and several other intergovernmental agencies also participate in setting regulatory standards in insurance. Table 3 presents the working relationships of selected agencies.

IV. Concluding Remarks

22

The FSB notes that the target groups for this regulatory initiative are Global Systemically Important

Financial Institutions (G-SIFIs).

P a g e | 21

How do we picture the regulatory authority that helps us enjoy quality, fairly priced products and services from reliable financial institutions? We portray one whose concern is not about endlessly designing new frameworks but working to “ascertain safety and effectiveness” (Stiglitz, 2009) in the regulated market and who is mindful of balancing social and economic welfare benefits and costs. We need the regulators who know that regulation by itself is costly and fear risk of government failure. We need them to be able to stay proactive, minimize the impact of market imperfections and remain countercyclical to prevent market failures. We need the ones who can align societal and economic welfare in the economy. We need the ones who only attend to local market matters but also enhance the country’s participation in regional and international coordination and cooperation. In a “good” state, societal and economic fundamentals stay solid and principles of regulation should not be fragile and the rules that government uses to guard those fundamentals and principles stay dynamic.

One of the key outcomes of the Dodd-Frank Act is that the U.S. now has a central point of contact

– the Federal Insurance Office – for the international insurance sector and for insurance supervisors globally. The FIO became a full IAIS member in October 2011 and began to participate in the regulatory initiatives covering SIFI supervision and the ComFrame. Besides, it also works with the U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council to manage threats to financial system stability. It is, however, not clear who represents the U.S. in the global insurance regulatory community – the FIO, the NAIC or state governments? For instance, the IAIS members for the year of 2010 include the NAIC, Arizona, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma as well as the FIO (new in 2011). What has long been missing within the U.S. is a clearly defined interconnectedness of the regulatory authorities and their duties.

It is also not clear whether the U.S. will become a more active influencer in setting global standards in insurance regulation and supervision.

23

Solvency II and the ComFrame, for example, are a great concern for the EU because the main European insurance market is dominated by insurance groups and in part by financial conglomerates (CEA, 2011). The international supervisory challenges the U.S. faces also include the solvency modernization initiative, accounting standards (maintenance of SAP or convergence to U.S. GAAP in compliance with

IASB standards), reinsurance collateral, state-based licensing regulation, and data confidentiality in regulating G-SIFIs.

23

At the time of writing, the NAIC, the FIO and state insurance commissioners represent the U.S. in key intergovernmental agency activities. For example, the NAIC staff and insurance commissioners are assigned to the Executive Committee and eight other main committees of the IAIS. The U.S. holds vice chairpersonship for two of the IAIS main committees: the Financial Stability Committee and the Supervisory

Forum. The NAIC holds chairpersonship of the Joint Forum (Source: the NAIC).

P a g e | 22

References

CEA (2011). “Essential Adjustments for the Success of Solvency II for Groups,” CAE Position Paper ECO-

SLV-11-729 (October 28).

Chan-

Liu, Jorge (2010). “The Globalization of Finance and its Implications for Financial Stability: An

Overview of the Issues,” Social Science Research Network Paper 1008837.

http://ssrn.com/abstract=1008837 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1008837.

Claessens, Stijin and Kristen Forbes (2001), International Financial Contagion , Springer.

Eatwell, John (2009). “Practical Proposals for Regulatory Reform,” in Subacchi, Paola and Alexei Monsarrat

(eds.), New Ideas for the London Summit: Recommendations to the G20 Leaders , A Chatham House and Atlantic Council of the United States Report.

Financial Stability Board (2011). Policy Measures to Address Systemically Important Financial Institutions

(November 4). http://www.bundesbank.de/download/bankenaufsicht/pdf/2011_11%2004_fsb_sifi_measures.pdf.

Fortune.com (2008). Fortune Global 500 . http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/global500/2008/full_list/.

Geneva Association (2011). Consideration for Identifying Systematically Important Financial Institutions in

Insurance , (April). http://www.genevaassociation.org/PDF/BookandMonographs/GA2011-

Considerations_for_Identifying_SIFIs_in_Insurance.pdf

Institute of International Bankers (2010). Global Survey 2010: Regulatory and Market Developments . http://www.iib.org/associations/6316/files/2010GlobalSurvey.pdf

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (2010). Global Reinsurance Market Report (December

22). http://www.iaisweb.org/__temp/IAIS_Global_Reinsurance_Market_Report_2010_endyear_edition.pdf.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (2011). Issues Paper on Resolution of Cross-Border

Insurance Legal Entities and Groups . http://www.iaisweb.org/__temp/Issues_paper_on_resolution_of_crossborder_insurance_legal_entities_and_groups.pdf.

Insurance Information Institute (2012). Insurance Factbook 2012 , New York: III.

Insurance Information Institute (2003). Financial Services Factbook 2003 , New York: III.

International Regulatory Cooperation (G) Working Group (2012). Meeting Summary Report (March 3), New

Orleans: 2012 Spring National Meeting of the NAIC. http://www.naic.org/meetings1203/summary_g_ircwg.htm.

Michael White-Prudential Report (2012). Bank Insurance Brokerage Registers Record 3 Quarters .

Nicols, Robert (2009). “Principles for Financial Supervision Reform,” a chapter in Subacchi, Paola and

Alexei Monsarrat (eds.), New Ideas for the London Summit: Recommendations to the G20 Leaders , A

Chatham House and Atlantic Council of the United States Report. http://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/International%20Economics/r0409_g2

0.pdf.

Payne, David and Fenwick Yu (2011). “U.S. Trade in Private Services,”

Economics and Statistics

Administration (ESA Issue Brief #01-11), Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce. http://www.esa.doc.gov/sites/default/files/reports/documents/esaissuebriefno1.pdf.

Sidley Austin, LLP (2012). 2012 Insurance & Reinsurance Law Report . http://www.sidley.com/files/News/107f11b9-a65d-45ec-b2ea-

00c5fe8698d5/Presentation/NewsAttachment/7649d46f-a5df-45b9-806b-020643002e5b/2012-

SidleyAustinLLP-IRLR-WEB.pdf.

P a g e | 23

Skipper, Harold D. and W. Jean Kwon (2007). Risk Management and Insurance Perspectives in a Global

Economy , John Wiley-Blackwell.

Stiglitz, Joseph (2009). “Regulation and Failure,” in Moss, David and John Cisternino (eds.), New

Perspectives on Regulation , The Tobin Project.

Vaugha n, Terri (2011). “Supervising Internationally Active Insurance Groups,” a presentation at the

Insurance Institute of London (February 17). http://www.naic.org/documents/cipr_vaughan_london_international_group_supervision.pdf.

White, Lawrence J. (1996) ‘Competition versus Harmonization: An Overview of International Regulation of

Financial S ervices’, in Claude E. Barfield, ed.,

International Financial Markets: Harmonization versus

Competition , AEI Press.