THE VOTING RIGHTS RATCHET: ROWE v ELECTORAL

advertisement

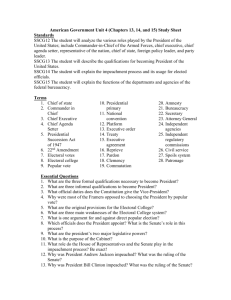

Graeme Orr, ʻThe Voting Rights Ratchetʼ (2011) 22(2) Public Law Review 83-89. At the end of this paper is an addendum on Specific Implications of Rowe for electoral law. THE VOTING RIGHTS RATCHET: ROWE v ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER THE GENESIS OF VOTING RIGHTS JURISPRUDENCE: FROM ONE-VOTE, ONE-VALUE TO PRISONER VOTING In Westminster tradition, the ability to vote was fundamental to parliamentary democracy, yet simultaneously a privilege regulated by Parliament. While the trend to liberalise the franchise seems, in retrospect, an inexorable tide, significant forces were arrayed on all sides of what the Victorian era knew simply as the “reform” debate. Conservatives saw voting less as a right than a responsibility. It was to be restricted to those responsible for – and given independent status by – landholdings. The democratic instincts of the Chartists held greater sway in Australia, where women won the vote for national elections as early as 1902, 16 years before British suffragettes. Yet Australia was no “paragon of virtue”.1 The Commonwealth began with a racist franchise,2 and only enfranchised most Indigenous people in 1962. The tension between voting as a republican ideal and an individual responsibility is neatly captured today in laws compelling both enrolment and attendance at the polls. Similar to the United States, the Australian Constitution erects no explicit grant of the franchise.3 The closest it came to the matter was in s 41, now neutered by narrow interpretation. The original intent appears to have been to leave the definition of the national franchise to Parliament (indeed the 1891 draft left the matter, in hyper-federalist United States style, to the separate States).4 The great issues of the day were including women and excluding non-white races. Trust in parliamentary sovereignty is reflected in ss 8 and 30, leaving to Parliament the definition of the “qualification of electors”, a power explicitly limited only by a prohibition against plural voting.5 Nevertheless, in a series of cases between 1975 and 2006, the High Court crafted a presumption of universal suffrage, out of the general requirement, in ss 7 and 24 that Parliament be “directly chosen by the people”.6 The cornerstone of these decisions was McKinlay’s case. In retrospect it seems an inauspicious source: McKinlay and others sought to import United States jurisprudence mandating one-vote, onevalue, but were rebuffed 6-1.7 Barwick CJ scathingly remarked that the Constitution was a site for literalism, not for “resort[ing] to slogans or to political catch-cries or to vague and imprecise expressions of political philosophy”.8 Yet, along the way, McTiernan and Jacobs JJ argued that while “chosen by the people” did not require equal weighting of votes: the long established universal adult suffrage may now be recognized as a fact and as a result it is doubtful whether ... anything less than this could be described as a choice by the people.9 This insight was embedded in precedent in the prisoner voting case, Roach v Electoral Commissioner.10 However, the constitutional presumption of a universal franchise appears limited to adult citizens, and is subject to legislated exceptions that are proportionate or reasonably consistent to representative government. 1 Brooks A, “A Paragon of Democratic Virtues? The Development of the Commonwealth Franchise” (1993) 12 UTasLR 208. 2 Chesterman J and Philips D, Selective Democracy: Race, Gender and the Australian Vote (Melbourne Publishing Group, Armadale, 2003). 3 For an overview, see Orr G, The Law of Politics: Elections, Parties and Money in Australia (Federation Press, Annandale, 2010) Ch 3. 4 An approach fortunately ditched in the 1897 draft. 5 That is, wealthier persons having several votes because of multiple residencies or landholding. 6 Critiquing this judicial implication, and lamenting the failure to develop the explicit provision in s 41, see Twomey A, “The Federal Constitutional Right to Vote in Australia” (2000) 28 Fed LR 125. 7 Attorney-General (Cth); Ex rel McKinlay v Commonwealth (1975) 135 CLR 1. Similarly, see McGinty v Western Australia (1996) 186 CLR 140. For deeper discussion, see Twomey, n 6 at 146-151. 8 Attorney-General (Cth); Ex rel McKinlay v Commonwealth (1975) 135 CLR 1 at 17. 9 Attorney-General (Cth); Ex rel McKinlay v Commonwealth (1975) 135 CLR 1 at 36. Similarly see McGinty v Western Australia (1996) 186 CLR 140 at 201 (Toohey J), 221-222 (Gaudron J); Langer v Commonwealth (1996) 186 CLR 302 at 342 (McHugh J). 10 Roach v Electoral Commissioner (2007) 233 CLR 162 (a 4:3 holding that “short-term” prisoners could not be denied the vote). For discussion of Roach’s implications, see Orr G and Williams G, “The People’s Choice: The Prisoner Franchise and the Constitutional Protection of Voting Rights in Australia” (2009) 8 Election LJ 123. THE ROLE OF WRITS AND WRITING OF THE ROLLS: THE GENESIS OF EARLY ROLL CLOSURE Electoral writs are customary documents of some antiquity. Modern lawyers are familiar with the writ of summons in judicial process, but electoral writs are cornerstones of parliamentary practice. They operated as a command of the monarch, to summons the sheriffs (later Chancery) to ensure the selection of knights, as part of the process of summonsing the knights so “returned” to attend the new Parliament.11 Although hardly indispensable, writs remain important formalities.12 They help address two issues. Since there is a writ for every seat or constituency, it is not possible to petition an election as a whole. One has to challenge the return of particular members. The other issue is the setting, in the writ, of the key dates for an election. The most notable dates are the close of nominations, polling day and the date for closure of the electoral rolls.13 The electoral roll is the humble technology tethering the great but abstract “right to vote” to the pragmatics of the everyday. Once compiled annually by hand, the “roll” now exists not as a physical register but as continuously updateable computer files, which are mined to create “certified lists” of electors, at any point in time, for any electoral event. This administrative task is reinforced by continuous data-matching and, since 1911, by a legal obligation to maintain enrolment.14 The roll is unimpeachable and only those on the roll can vote, unless they can establish their name was omitted in error.15 The practice for most of the 20th century was for Prime Ministers to announce an election but then delay the issuing of the writ. As Hughes and Costar demonstrated, the average length of time between election announcement and the writ was 19 days.16 This convention ensured ample time for electors to learn of the impending election and ensure their enrolments were in order.17 It was broken by Prime Minister Fraser’s snap double dissolution election of 1983. Electors who had no time to make the national electoral roll tried to argue their disenfranchisement, relying on the apparent constitutional guarantee in s 41, but the High Court decided that was a spent provision.18 In response, the incoming Hawke government legislated to provide a grace period of seven days between the writ and the close of rolls. A commonplace struggle in electoral democracy worldwide is between conservatives, fearing electoral rorting, who argue for tighter procedures and progressives, concerned to avoid disenfranchisements, who argue for voting to be as accessible as possible. After the Hawke government reform, some conservatives queried whether the electoral authorities could handle a deluge of last-minute enrolments. The Australian Electoral Commission responded that while it was virtually impossible to screen every enrolment, it could handle the rush and an audit had found only 0.02% of last-minute enrolments were erroneous.19 As late as 2003, a multi-party committee with a conservative majority supported the seven-day grace period.20 However, Coalition policy turned against the grace period, and on securing a Senate majority, the Howard government overturned it.21 No new enrolments were to be added after 8pm on the day the writ issued, and changes to addresses closed three days later. Presaging that move, the Coalition majority on the parliamentary electoral matters’ committee had asserted in 2005 that early roll closure was important for two reasons. One was that the volume of enrolments in the grace period limited integrity checks. (Admitting a lack of evidence of fraud, the committee majority argued that early roll closure could be prophylactic). The other reason was to 11 Riess L (tr Wood-Legh KL), The History of the English Electoral Law in the Middle Ages (Octagon Books, NY, 1973) pp 17-19. 12 With a fixed election date, Australian Capital Territory elections cope without a writ. Legislation sets the timelines, with any unpredictable dates being set directly by the executive: Electoral Act 1992 (ACT), Pt 9. 13 See further Orr n 3, pp 92-94. 14 On enrolment and the roll, see Orr, n 3, Ch 4. 15 For example, Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth), s 221(3) (conclusiveness of roll), s 235 (provisional voting by those erroneously omitted from roll). 16 Hughes CA and Costar B, Limiting Democracy: The Erosion of Electoral Rights in Australia (UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006) p 47. A writ must issue within 10 days of the expiry or dissolution of the House of Representatives: Constitution (Cth), s 32. 17 Under longstanding legislation, roll changes had to be received by the issue of the writ: eg Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (Cth), s 64. 18 R v Pearson; Ex parte Sipka (1983) 152 CLR 254. Section 41 says that an adult with “a right to vote” for a State lower house shall not be “prevented from any law of the Commonwealth from voting” at federal elections. 19 Hughes and Costar, n 16, pp 49-50. 20 Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, The 2001 Federal Election (Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2003) pp 56-63. 21 Electoral and Referendum (Electoral Integrity and Other Measures) Act 2006 (Cth). encourage electors to make timely enrolment in line with their legal obligations, presumably by discouraging a sense that enrolment could be left to the last minute.22 Opponents of the move, such as Hughes and Costar, called it “slamming the door” on valid enrolments, rather than a move to enhance roll integrity. Excluding tens of thousands of valid lastminute enrolments, to guard against a few undue ones, made the roll decidedly less comprehensive. Restricting enrolment opportunities also impacts disparately on new enrolees – predominantly young and new citizens – and those who move residence frequently or live in remote regions. For its part, the Rudd Labor government had a policy of restoring the grace period but faced conservative opposition in the Senate. Like prisoner voting, the issue seemed destined to continue as a form of political ping pong.23 While Prime Minister Gillard could have subverted early roll closure by reverting to the old convention of announcing the 2010 election well ahead of issuing the writs, she chose a short campaign. The election was announced on a Saturday, with the writs issuing on the Monday evening.24 This contrasted, ironically, with Prime Minister Howard. Having legislated for early roll closure, he allowed several days grace by announcing the 2007 election on a Sunday, with writs to issue the following Wednesday. The larger point is that whenever the rolls are legislated to close, Australia’s Constitution still reserves federal election dates to executive whimsy. THE DECISION IN ROWE V ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER In Rowe v Electoral Commissioner,25 two plaintiffs challenged early roll closure: Shannon Rowe, who had turned 18 a month before the writ issued, and Duncan Thompson, who was enrolled but had moved several months earlier into a different electorate. Neither met the enrolment cut-offs. For Rowe that meant the prospect of no ballot at all; for Thompson it meant voting for candidates in his old electorate. By a majority of 4:3, the High Court upheld the plaintiffs’ claim, and hence the law reverted to the earlier, seven-day grace period. The timelines for the conduct of the case reveal the High Court in both its most responsive and leisurely modes. Given the imminence of the election – and the need, if the law were to be overturned, to give the Australian Electoral Commission time to process newly permissible enrolments – the case was expedited at break-neck speed. Within days of the plaintiffs’ initial filing, a directions hearing was concluded. The full hearing occurred within a week, and final orders in the plaintiffs’ favour were handed down the next day. Yet once that urgency had passed, their Honours took over four months to craft their reasons, spanning six separate judgments and 163 pages. The three majority opinions, of French CJ, Gummow and Bell JJ, and Crennan J, can be summarised as insisting on a rational connection between measures limiting the ability to vote, and a legitimate governmental aim. This test draws on Roach’s case.26 In French CJ’s judgment, the 2005 parliamentary committee merely asserted an interest in limiting the possibility of fraud and in goading electors to comply with the obligation of timely rather than last-minute enrolment. Such assertions “addressed no compelling practical problem or difficulty”.27 Similarly, Gummow and Bell JJ argued that “[a] legislative purpose of preventing ... fraud ‘before it is able to occur’, where there has been no systemic fraud” could not justify an unduly restrictive cut-off.28 In response to the argument that enrolment was a mere process requirement, and not a disqualification from the franchise as such, their Honours observed that inability to enrol was tantamount to denying the franchise,29 and that on a rough estimate at least 100,000 people were in the plaintiffs’ position of responding to the election but missing the cut-off. As in Roach, the majority judges made much of what they saw as a practical and ethical consensus that had evolved through 22 Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, The 2004 Federal Election (Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2005) pp 34-36. 23 Contrast the Labor/Greens’ position with the Coalition Members of Parliament support of early roll closure: Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Report on the Conduct of the 2007 Election (Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2009) pp 49-51, cf pp 325-326. 24 A point averted to in Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 by Hayne J at [239] and, in a more barbed way, by Heydon J at [269]. 25 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213. 26 In particular Gleeson CJ’s judgment, see Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [23] (French CJ), [123] and [161] (Gummow and Bell JJ). 27 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [78]. 28 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [167]. 29 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [154]. most of the 20th century, in this case to give people a reasonable time to enrol after an election had been called. For Hayne J, in dissent, the question required a literalist framework. Does a law closing the rolls on the evening of the writ yield a Parliament not directly chosen by the people?30 He distinguished Roach’s case as inapposite, since Roach involved qualifications to be part of “the people”, whereas Rowe and others like her had not just the right but an obligation to enrol and had “through their own inaction” failed to do so in time.31 Hayne J acknowledged that the 20th century expansion of the franchise was an evolutionary and inclusionary development. But in retort to the progressivist method of the majority, he saw this as evidence of the political dynamism of sovereign, representative government. He thus repeated his critique from Roach that ratcheting such contested, political developments into entrenched constitutional norms is a kind of boot-strapping.32 Heydon J, also in the minority, gave a pungent judgment, the essence of which was that the plaintiffs were “the authors of their own misfortunes”.33 The law obliged them to enrol in a more timely fashion and they had not done so. Heydon J also hewed to his avowedly originalist approach to constitutional interpretation, in contrast to the majority’s living tree approach.34 Nonetheless, his Honour appears resigned to the originalist approach being out of contemporary favour. Indeed, in a suitably originalist, indeed pompous, metaphor he portrayed originalism as “[s]timulating as much approbration as the man who asked for a double whisky in the Grand Pump Room at Bath”.35 This Roddy Meagher-like rhetoric extended to disparaging the plaintiffs making a submission about the disparate impact of early roll closure without attempting to build any constitutional case out of it. Such evidence of a “supposed impact of the impugned provisions on Australia’s young adults as well as its wretched of the earth – its descamisados and other victims … had [no] point other than an appeal to pathos”.36 For their parts, Crennan J’s and Kiefel J’s judgments were interesting less for the way they reasoned to their rationes, than in their journeys down interesting rabbit holes. The bulk of Kiefel J’s judgment was an excursion into the law of proportionality, which culminated in her clearing leeway for the Parliament and concluding that early roll closure was not without justification.37 Crennan J’s majority opinion, by contrast, is of direct interest to electoral scholars, for she devoted six pages to a thesis that 19th century Australian colonial practice represented a triumph of egalitarian political values over an oligarchic British inheritance. (This thesis reprised a speech she gave to the 2008 Constitutional Law Dinner in Sydney, in which she valorised the Australian Chartists, particularly the goldfield diggers.)38 This romantic narrative is invoked by Crennan J to inform a progressive, if not radical, reading of “chosen by the people”. The aim appears to be to uncover pre-Federation roots as supporting the living tree approach to constitutional rights and guarantees. Her Honour explicitly invoked Issacs J in the Skin Wool case, on the importance “in interpreting the Australian Constitution, of every fundamental constitutional doctrine existing and fully recognised at the time the Constitution was passed”.39 However, as a full-blown originalist like Heydon J would point out, the problem with such historicism is that the late 19th century Australian settlement of the franchise question only extended to universal male suffrage. It was class-free, but not necessarily free of gender discrimination and certainly not free of racial exclusions.40 30 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [182]. The question of whether there was a direct choice by the people appears to exhaust the electoral law consequences of representative government, according to Hayne J at [195], for “the Constitution says so little about the way in which representative government is to be implemented” (at [198]). 31 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [187]. See also [218]: it was sufficient that “the people” had the “legal opportunity” to participate. 32 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [201]-[204], [266]. 33 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [287]; see also [272] (arguing that the lack of fixed election dates was irrelevant because speculation before a Prime Minister calls a poll is usually notorious). 34 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [292]-[302]. 35 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [293]. (The Pump Room was a place for drinking fresh spa water.) 36 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [271]. 37 In contrast, Kiefel J saw the ban on any prisoner voting as completely lacking justification. See Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [482]. 38 Justice Crennan, “Reflections on Section 7 and 24 of the Constitution” (Speech delivered at the Gilbert & Tobin Centre of Public Law, Constitutional Law Dinner, February 2008), http://www.hcourt.gov.au/publications/speeches/current/speeches-byjustice-crennan-ac viewed 8 March 2011. 39 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [324], citing Commonwealth v Kreglinger & Fernau Ltd (1926) 37 CLR 393 at 411-412. 40 Brooks n 1; Chesterman and Philips, n 2; cf Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [292]-[311] (Heydon J). Curiously, the opinions in Rowe draw on almost no comparative law, aside from background references to 19th century British electoral registration. The fact that New Zealand and Canada permit enrolment up until and even on election day, respectively, suggests Australian practice is languishing. The more significant oversight – explicable by the hurried nature of the hearing – was the failure of the Commonwealth to defend early roll closure by analogy with United States case law. Despite a strong judicial interest in voting rights, the American Supreme Court has accepted registration cutoffs of 30 and even up to 50 days.41 Admittedly, the two electoral systems are not fully analogous: the United States has fixed terms and primaries and hence a well-defined electoral “season”, while Australia compels people to the polls. However the original source of the implied right to vote federally in the United States, as in Australia, was the constitutional mandate that the House of Representatives be “chosen … by the people”.42 CONCLUSION: THE RATCHET IS NOT RADICAL In the 35-year journey from McKinlay to Rowe, it is curious that vote weighting, which was the stormiest electoral issue in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in the geographically largest States, has now been put to bed by a political consensus in favour of one-vote, one-value.43 Yet the franchise, a first-order liberal issue largely thought resolved by Edwardian times, has recrudesced to centre stage. The franchise of prisoners and expatriates, and its denial to permanent residents, are all topical matters. More pragmatically, the state of the rolls has moved to centre stage. Over 1.4 million eligible citizens were estimated to be absent from the 2010 rolls. The overwhelming cause was not early closure, but the use of official data revealing address changes to cleanse the rolls, but not to update them. State legislative reforms moving to a system of “automatic enrolment” are to be implemented in New South Wales and Victoria. These States and Queensland will also allow new voters effectively to enrol until polling day by claiming a provisional vote, a vote that is counted once their bona fides are checked. But these reforms remain controversial with federal conservatives. Given the ease with which data can be matched electronically, arguments about processing enrolment forms and timelines born of a paper-era seem increasingly arcane. If automatic enrolment is not in place by the next federal election, another court challenge is foreseeable. Could it, or other envelope-expanding claims – say by expatriates to wider voting rights – succeed? The majority, in Roach and Rowe, was progressive in its methodology and outcome, but only modestly so. The court is careful to repeat the mantra that it is not its place to judge parliamentary motivations.44 Hence, even in an area as prone to partisan feather-bedding as electoral law, it shows little signs of moving to a strict-scrutiny approach. Nor is the search for “rational justification” a thorough-going one, with the court insisting that the law be as rationally tailored to constitutional goals as possible. Rather, the majority is identifying values it sees as entrenched by long convention – such as universal suffrage or a grace period for enrolment – and guards them against legislative backtracking by demanding cogent justifications. So while Heydon J claimed that the logic of Rowe’s position was that “there should be the widest possible participation in elections [with enrolment] right up to the moment when the polling booths closed”,45 such a claim would be unprecedented. The majority’s method, through which constitutional norms are created, but in hindsight, is known in the American idiom as “ratcheting”. The ratchet offends originalists because it works in only one direction, and carries the conceit of history as a story of progress without regress. (In contrast, the past being another country, especially technologically the originalist position can seem ludicrous when applied to fundamental practicalities such as electoral enrolment).46 The ratchet is not a radical technique compared to the search for overarching principles in implied rights jurisprudence. It is more shield than sword; those long excluded from the franchise, like permanent residents, cannot employ it to gain inclusion. In one respect, Rowe’s case is quite American. The case was argued by pro bono lawyers assembled by Get Up!, a non-partisan, left-wing organisation akin to the United States movement moveon.org, which mobilises sympathisers through on-line petitions and donations. Get Up! also ran a successful Federal Court claim just prior to the 2010 election, to permit online electoral enrolment.47 41 Burns v Fortson 410 US 686 (1973); Marston v Lewis 410 US 679 (1973). Dunn v Blumstein 405 US 330 at 348 (1972) found that 30 days was an “ample period of time ... to complete whatever administrative tasks are necessary to prevent fraud”. 42 United States Constitution, § 2.1. Amendments subsequently prohibited a racialised (1870) or gendered (1920) franchise. 43 Orr, n 3, pp 29-30. 44 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [166] (Gummow and Bell JJ). 45 Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [278]. 46 Compare Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 85 ALJR 213 at [292]-[302] (Heydon J) using 19th century British practices of annual compilation of the roll by revising barristers as a constitutional yardstick. 47 GetUp Ltd v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 189 FCR 165. Public interest litigation in the law affecting Australian democracy has tended to be ad hoc and dominated by quixotic litigants-in-person,48 rather than concerted and driven (as in the United States) by groups such as the Brennan Center for Justice. While incremental rather than radical, the ratchet does invite further test cases, and in Get Up! there is now a litigational vehicle to drive that process. Graeme Orr Associate Professor, Law School, University of Queensland The author gave pro bono help to the plaintiffs’ legal team in Rowe’s case on comparative United States law. An earlier version of this comment was delivered to the University of Western Australia Law School. Challenges of Electoral Democracy Workshop Melbourne 14‐15 July 2011 Panel 1: The High Court in Rowe v Electoral Commissioner and its Implications Specific Implications for Electoral Law – Comments by Graeme Orr Ramifications of Rowe for electoral law can be divided into two categories: 1. Enrolment Issues 2. Electoral Regulation more Broadly Enrolment Issues (a) National level. The Rowe case does not constitutionally mandate generous periods for enrolment – eg polling day registration. On the contrary, judges on both sides implied that was not required. But with such procedures being mooted and implemented, in a decade or two it will be highly arguable that such more generous timescales will not be able to be undone, short of evidence of problems with workability, eg fraud. (b) State electoral level. States should ensure their cut‐off dates are not unduly early. Formally this will only apply in States with some constitutionally mandated franchise, although this may easily be implied. (Eg Constitution Act 2001 (Qld) s 10 says that ‘the Legislative Assembly is to consist of directly elected members to be elected by [eligible] inhabitants of the State’.) The High Court in Rowe did not decree that every State roll must remain open for a week from the writ. That period was an implication drawn from historical practice at Commonwealth level, and the inability of the Commonwealth to justify earlier roll closure. However unless the States can show cogent reasons for earlier closure, a rule of 1 week from the writ will be a safe harbour. This is particularly so in Queensland where, like the Commonwealth, there is no fixing of parliamentary terms. 48 See discussion in Gageler S, “The Practice of Disputed Returns for Commonwealth Elections” in Orr G, Mercurio B and Williams G (eds), Realising Democracy: Electoral Law in Australia (Federation Press, Annandale, 2003) Ch 14. (c) Local government level. Ramifications may arise where State/Territory constitutions mandate local government elections (since it is an easy step to then imply a broad and accessible franchise). Eg Constitution Act 2001 (Qld) s 71(1) provides that ‘a Local Government is an elected body’. But again, nothing in Rowe formally decrees that local government rolls be open for some period after each election is called. Indeed the reasoning in Rowe may be distinguished in that, unlike Commonwealth election dates, local election dates are typically set well in advance and by legislation: eg Local Government Act 2009 (Qld) s 269 sets the ‘last Saturday in March’ every four years. But in the US, despite fixed election dates, the Supreme Court has essentially mandated hat registration cannot close more than 40 days before polling day. Some very short local roll closing dates may therefore be prima facie challengeable: eg Qld s 277 requires rolls to close about 2 months before local polls. In response the Queensland government could argue that since returning officers are the council CEOs, rather than full‐time electoral officials, it is reasonable to give them more time. Election Regulation more Broadly (a) Nomination cut‐offs. An obvious cognate to enrolment cut‐offs are nomination cut‐ offs. After all, candidates are as crucial to the Constitutional mandate of ‘directly chosen’ as electors. The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) requires a minimum 10 days from the writ for candidates to nominate. Following the Rowe approach, significantly reducing that period without cogent evidence of a need to do so will be constitutionally suspect. (b) The Franchise. The ‘vibe’ of Roach (the Prisoner Voting case) and Rowe, read together, is that the Court will erect a shield to prevent backtracking on fundamental electoral rights and freedoms if (a) there is a history of a long legal or social consensus around those rights and freedoms and (b) there is a lack of a strong justification to reduce the benchmark. This ‘ratchet’ approach however is not a constitutional sword. For instance the Court would not extend the constitutional idea of ‘the people’ to enfranchise non‐citizen permanent residents. It might, at least given a decade or so, come to see eligible overseas electors as a prima facie protected category. That is, a future parliament would be required to give cogent justifications to pull back from the 6 year rule (enabling ex‐pats intending to return within 6 years to remain on the roll). That is even more likely if the social recognition of the diaspora and globalising trends continue. Professor Costar has even suggested that Darryl Melham’s desire to disenfranchise the privileged British subject non‐citizens could be constitutionally suspect under the High Court’s approach. I doubt that. Even Chief Justice Gleeson (a majority voice in Roach) volunteered that it was within Parliament's power to use citizenship as a symbolic boundary around the franchise. (c) And beyond … Political Finance? Methodological conservatives loathe the 'loosey‐ goosey' incursion of the High Court into the old principle of pure parliamentary sovereignty, even in an area as fundamental as electoral law. But judicial 'activism' is not a one‐way, progressive force – as the Roberts' Supreme Court in the US is today making abundantly clear (see the Citizens United and Arizona Free Enterprise Club cases). What is good for the progressive goose can be good for the ideologically conservative gander. Rowe (and Roach) fit into the implied rights agenda, begun in 1992 in the striking down of the UK style egalitarian ban on paid electoral broadcasts (ACTV case). Conservatives will search in Rowe and Roach to buttress their arguments against expenditure and donation limits. Freedom of political donation, for instance, has been part of the Australian heritage for 110 years until last year's NSW reforms. But Rowe and Roach deal with the universal franchise, which is directly drawn from the Constitutional terms 'chosen' by the 'people'. Political speech and fund‐raising are a step removed: a freedom of political communication is indirectly implied from those Constitutional terms. The High Court, I predict, will be wary of finding that political finance restrictions are unjustifiable.

![PLEWA joint panel presentation [MS PowerPoint Document, 132.7 KB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005388913_1-9a663c909a47d520a5a627c8de595641-300x300.png)