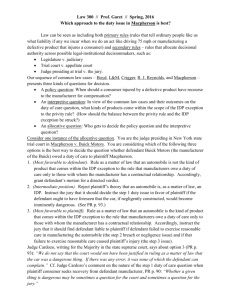

product liability update

advertisement

PRODUCT LIABILITY UPDATE Presented and Prepared by: Michael D. Schag mschag@heylroyster.com Edwardsville & Chicago, Illinois • 618.656.4646 Prepared with the Assistance of: Brett M. Mares bmares@heylroyster.com Edwardsville, Illinois • 618.656.4646 Heyl, Royster, Voelker & Allen PEORIA • SPRINGFIELD • URBANA • ROCKFORD • EDWARDSVILLE • CHICAGO © 2012 Heyl, Royster, Voelker & Allen J-1 PRODUCT LIABILITY UPDATE I. POST-JABLONSKI METHODS OF PROOF .............................................................................................J-3 A. B. C. D. II. THE INTERPLAY OF DUTY AND RELATIONSHIP ................................................................................J-6 A. B. C. III. Competing methods .....................................................................................................................J-3 The Panther Platform and Fuel Tank Integrity ....................................................................J-4 The Jablonski Court’s Analysis ...................................................................................................J-5 Jablonski’s Lasting Impact ...........................................................................................................J-6 Simpkins v. CSX Corp. ...................................................................................................................J-7 Holmes v. Pneumo Abex ...............................................................................................................J-7 Why These Cases Are Important ..............................................................................................J-9 THE LEARNED INTERMEDIARY DOCTRINE ..........................................................................................J-9 A. B. C. Wendell v. Johnson & Johnson...................................................................................................J-9 Hernandez v. Schering Corp. .................................................................................................... J-10 A Continued Strengthening of Protections for Drug Manufacturers ...................... J-13 The cases and materials presented here are in summary and outline form. To be certain of their applicability and use for specific claims, we recommend the entire opinions and statutes be read and counsel consulted. J-2 PRODUCT LIABILITY UPDATE I. POST-JABLONSKI METHODS OF PROOF A. Competing methods Product liability cases based on negligence adhere closely to common law jurisprudence. Looking past the conventional formula of the need to prove duty, breach of duty, injury and proximate causation, the key question in a negligent design case is whether the manufacturer of the product at issue exercised “reasonable care” in designing the product. Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp., 224 Ill. 2d 247, 270, 864 N.E.2d 249 (2007). In evaluating this question, one must ask “whether in the exercise of ordinary care the manufacturer should have foreseen that the design would be hazardous to someone.” The plaintiff must therefore prove that the manufacturer “knew or should have known of the risk posed by the product design at the time of manufacture.” Calles, 224 Ill. 2d at 271. In 2007, the Illinois Supreme Court’s oft-criticized decision in Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp. upheld, as part of this evaluation, implementation of the “risk-utility balancing test” in order to determine the reasonableness of the manufacturer’s actions. Id. at 269. As described in the Restatement (Second) of Torts § 291, the test compares “the risks inherent in the product design” and “the utility of benefit derived from the product.” Thus, negligence results if the risk caused by the product is of such magnitude that it outweighs the utility of the product. The two primary factors to be considered in turn are whether there were feasible alternative designs available at the time of manufacture, and whether the design the manufacturer used conformed to industry standards, authoritative voluntary organizations, or regulatory criteria. Id. at 267. For example, at one end of the risk-utility spectrum would be a child’s toy that contains lead paint. This product offers an allegedly high risk of medical problems to the children who come into contact with it, and only the slight utility of entertainment. On the other end of the riskutility spectrum would be a pencil, providing users with a great deal of utility and very little risk of injury. Most products, such as cars, fall somewhere in between these two extremes. The risk-utility test is just one of several ways to approach a negligent design case. In 2008, the Illinois Supreme Court decided Mikolajczyk v. Ford Motor Co., 231 Ill. 2d 516, 901 N.E.2d 516 (2008), in which it held that the risk-utility test is not a “theory of liability,” but is instead one of several “methods of proof by which a plaintiff ‘may demonstrate’ that the element of unreasonable dangerousness is met.” Mikolajczyk, 231 Ill. 2d at 548. Another theory of liability, the “consumer expectation test,” laid out in Restatement (Second) of Torts § 402A, demands that a plaintiff prove that a product is “dangerous to an extent beyond that which would be contemplated by the ordinary consumer who purchases it, with ordinary knowledge common to the community as to its characteristics.” Id. at 526. Thus, liability is the product of both the community’s “ordinary knowledge” and the level of danger associated with the product. A gun J-3 manufacturer is therefore likely to escape liability, while the maker of a defective over-thecounter cold medication would, under this analysis, be held liable for resulting injuries. B. The Panther Platform and Fuel Tank Integrity In 2003, as John and Dora Jablonski were travelling through Madison County, Illinois in their 1993 Lincoln Town Car, another car, travelling at approximately 65 miles per hour, rear-ended the Jablonskis after they had come to a complete stop in traffic. Jablonski v. Ford Motor Co., 2011 IL 110096, ¶ 3. A large pipe wrench in the trunk of the Town Car pierced the forward wall of the trunk, rupturing the car’s gas tank and resulting in a fire. Mr. Jablonski died as a result, and his wife was severely and permanently disfigured. Mr. Jablonski’s estate and his surviving wife brought suit against Ford Motor Company, alleging that the company negligently designed and located the fuel tank in the 1993 Lincoln Town Car. Much of the trial focused on whether the location of the fuel tank was “reasonably safe.” Jablonski, 2011 IL 110096, ¶ 9. In the 1960s and 1970s, most passenger cars had “aft of axle” fuel tanks, which were located behind the car’s rear axle and laid parallel between the bottom of the car’s trunk (the “package tray”) and the road. Id. at ¶ 7. This meant that, in many cases, the fuel tank came within inches of the vehicle’s rear bumper. The aft of axle tanks resulted in a relatively high incidence of fuel-fed fires upon impact, even at low speeds. Auto makers started searching for a new, safer place to locate the fuel tank. In 1979, Ford introduced the Panther platform, upon which the bodies of many of their four door passenger vehicles sat for over a decade of model years. Id. at ¶ 8. The Panther platform enlisted a “vertical behind the axle” fuel tank, still located aft of the rear axle, but protected on either side by the rear wheels, and situated vertically between the forward wall of the car’s trunk and the rear passenger seats. Id. at ¶ 8. This left approximately 40 inches of trunk space between the fuel tank and the rear bumper of the car. By 1991, a majority of Ford vehicles had switched to fuel tanks situated forward of the rear axle, likely as a result of the growing consumer preference for front wheel drive vehicles. Id. at ¶ 9. Still, the Panther platform and the Ford Mustang, both rear wheel drive, made use of vertical behind the axle tanks. Other car makers, including Audi, BMW, Chrysler, General Motors and Volvo, continued to use aft of axle tanks. During trial, the plaintiffs’ experts testified that all aft of axle fuel tanks had a heightened risk of failing to maintain system integrity during a crash. Id. at ¶ 12. Specifically, “he stated that the aftof-axle tank was defective because it was located in the ‘crush zone’ in rear-impact collisions and was vulnerable to being punctured by trunk contents and vulnerable to being pushed into sharp objects in front of the tank.” Id. The plaintiffs’ experts testified that locating tanks forward of the axle, or horizontally above the axle, were the safest solutions, as puncture by trunk contents was a “well-recognized problem.” Ford engineers looked into these issues, and determined that they did not pose serious risk of harm. A 1970 internal memorandum indicated that placing the tank over the rear axle would be the best location, as it would be “[a]lmost impossible to crush the tank from the rear.” Id. at ¶ 19. J-4 This location would also provide enough distance from the back bumper to avoid deformation upon rear impact, while also protecting the tank from lateral impact with the tires, axle, and wheel houses. The memorandum indicated that the tank could be placed high enough above the package tray to avoid most puncturing objects. However, in the event it was punctured by trunk contents, engineers were confident that fuel would remain in the trunk, not the passenger compartment. Id. at ¶ 20. Moving the tank from this position was likely to cost $9.95 per car, and might result in other unforeseen risks. Id. at 22. C. The Jablonski Court’s Analysis The Illinois Supreme Court began its analysis by noting that a manufacturer has a non-delegable duty to design a reasonably safe product, and therefore the fundamental question that is to be answered in a negligent design case is whether the manufacturer exercised reasonable care in the designing of the product alleged to have caused the injury. Calles, 224 Ill. 2d at 270. The Jablonski court maintained, as in Calles, that the inquiry centers around “whether in the exercise of ordinary care the manufacturer should have foreseen that the design would be hazardous to someone,” and the plaintiff must demonstrate that “manufacturer knew or should have known of the risk.” Id. at 271. To do so, the Court again turned to the familiar risk-utility balancing test. The Court reasoned that “[w]hen the risk of harm outweighs the utility of a particular design, there is a determination that the manufacturer exposed the consumer to a greater risk or danger than is acceptable to society.” Jablonski, 2011 IL 110096, ¶ 84. Among the factors to be considered are availability of alternative designs at the time that the manufacturer produced the product; the used design’s conformity to industry standards, design guidelines provided by an authoritative voluntary organization; the utility of the product; safety aspects of the product; and the manufacturer’s ability to eliminate unsafe characteristics of the product without sacrificing utility or affordability. Id. at ¶ 85. In the end, the Illinois Supreme Court held that “[a] manufacturer is not required to guard against every conceivable risk, regardless of the degree of harm.” Id. at ¶ 96. Instead, the manufacturer’s obligations are more accurately reflected under the risk-utility balancing test, and plaintiffs were required to prove that Ford’s conduct in designing and locating the fuel tank was unreasonable by demonstrating “that the risk was foreseeable and that the risks inherent in the product design outweighed the benefits.” Id. Here, plaintiffs were unable to do so. First, the 1993 Lincoln Town Car “satisfied the specific federal fuel system integrity standards promulgated by the NHTSA for rear-end collisions,” and after an investigation, the NHTSA chose not to require that the tank be moved. Further, the car exceeded Ford’s more stringent internal crash test ratings. Id. The fact that Ford’s placement of the fuel tank was consistent with industry practices carried out by a large swath of carmakers at the time also tipped the risk-utility balancing test in Ford’s favor. Id. at ¶ 97. J-5 In order to outweigh these factors, plaintiffs would have had to prove that the foreseeable risk of the tank placement outweighed its utility. Id. at ¶ 98. However, Ford demonstrated at trial that moving the tank would have required a complete redesign of the vehicle, a drastic change that would have introduced other risks of equal or greater magnitude, “including fuel-fed fires from the filler pipe and tank rupture from other parts of the vehicle.” Id. at ¶ 101. Regarding supplemental shielding that could have been installed around the tank, the Court found that it would not have prevented the puncture that occurred in the present case. Id. at ¶ 106. The Court consequently concluded that “after balancing the foreseeable risks and utility factors, plaintiffs failed to present sufficient evidence from which a jury could conclude that at the time of manufacture, Ford’s conduct was unreasonable or that it had acted unreasonably in failing to warn about the risk of trunk contents puncturing the tank.” Id. at ¶ 107. D. Jablonski’s Lasting Impact Jablonski marks a significant shift for the Illinois Supreme Court. The Court overruled not only the jury’s more than $38 million verdict, but also its factual findings. Once there was a significant split in jurisprudence between the risk-utility test and the consumer expectation test, the use of each resting on the subject matter of the suit, the type of injury sustained, and a number of other factors. Jablonski demonstrates the Court’s growing preference for a product liability scheme which is more uniform, but also remains flexible for application to a wide variety of lawsuits. By refusing to use the consumer expectation test, but including a “non-exhaustive” list of factors to be included in a risk-utility analysis, it is likely that Jablonski represents a shift towards a riskutility test that includes consumer expectations within its analytical framework. This might leave plaintiffs with more challenging proof problems in product liability cases. The consumer expectation test was flexible, resting heavily upon “community knowledge,” and therefore leaving much to be decided by the intuitions and personal experiences of jurors. II. THE INTERPLAY OF DUTY AND RELATIONSHIP Illinois personal injury jurisprudence has long held that some relationship must have existed between the plaintiff and the defendant in order for the defendant to be held liable for injuries. “The touchstone of [the] court’s duty analysis is to ask whether a plaintiff and a defendant stood in such a relationship to one another that the law imposed upon the defendant an obligation of reasonable conduct for the benefit of the plaintiff.” Marshall v. Burger King Corp., 222 Ill. 2d 422, 436, 856 N.E.2d 1048 (2006). This relationship analysis is based upon public policy considerations, including the reasonable foreseeability of the injury, the likelihood of injury, the magnitude of the burden of guarding against the injury, and the consequences of so burdening the defendant. Marshall, 222 Ill. 2d at 436-37. Illinois courts also consider special relationships, which may give rise to an affirmative duty “to aid or protect another against unreasonable risk of physical harm.” Id. at 438. The question of duty has been the subject of some controversy, as J-6 exemplified by the “take home” asbestos litigation, in which an employee is alleged to have taken asbestos fibers home with him on his person or clothes, and subsequently exposed his family members to asbestos fibers, resulting in the family member’s asbestos-related illness. A. Simpkins v. CSX Corp. In 2010, the Illinois Fifth District Court of Appeals found in Simpkins v. CSX Corp., 401 Ill. App. 3d 1109, 929 N.E.2d 1257 (5th Dist. 2010) that “employers owe the immediate families of their employees a duty to protect against take-home asbestos exposure.” Simpkins, 401 Ill. App. 3d at 1119. In doing so, the Fifth District held that, while a duty still requires that the two parties stand in an applicable relationship to one another, “[t]he term ‘relationship’ does not necessarily mean a contractual, familial, or other particular special relationship. . . . As the Supreme Court has noted, ‘the concept of duty in negligence cases is very involved, complex, and indeed nebulous.’” The court added, “[E]very person owes every other person the duty to use ordinary care to prevent any injury that might naturally occur as the reasonably foreseeable consequence of his or her own actions.” Id. at 1113. (citations omitted). The court touched upon the four public policy considerations mentioned in Marshall. Still, the exception appeared poised to swallow the rule. The court’s analysis in Simpkins did little to illuminate the holding. The issue, the court writes, is not whether the employer “actually foresaw” the risk, but whether it “should have foreseen the risk.” “[W]e believe that it takes little imagination to presume that when an employee who is exposed to asbestos brings home his work clothes, members of his family are likely to be exposed as well.” Therefore, the harm was foreseeable. Id. at 1116. The court also finds that preventing against take-home exposure through substitution of products, issuance of warnings, and updating of hygienic practices is not unduly burdensome. Id. at 1118. Despite its findings of foreseeability and preventability, the opinion does not address the “likelihood of injury” in any detail. Instead, the court writes that the likelihood of contracting mesothelioma varies depending on exposure, and “the likelihood of developing such a disease from anything more than incidental exposure is not remote.” Id. at 1117. Additionally, several other jurisdictions have found that the relationship present here is not substantial enough that a duty can be built upon it. Id. at 1114. Thus, in the wake of Simpkins, defendants were left with a fluid and largely undefined schematic upon which Illinois’ relationship requirement is based, knowing only that “the scope of liability will be inherently limited by the foreseeability of the harm.” Id. at 1118. B. Holmes v. Pneumo Abex In May 2006, a month after Jean Holmes died of peritoneal mesothelioma at the age of 93, her estate brought an action to recover damages for wrongful death. Holmes v. Pneumo Abex, LLC, 2011 IL App (4th) 100462, ¶ 1. Her husband, Donald, worked at a Unarco asbestos plant in Bloomington, Illinois from 1962 to 1963. Holmes, 2011 IL App (4th) 100462, ¶ 7. Both JohnsManville and Raybestos supplied asbestos to the plant during that time period. The action J-7 alleges that, while working at the Unarco plant, Donald brought home asbestos fibers on his person and on his clothes, resulting in his wife’s exposure, illness, and death. The science of take home asbestos exposure was slower to develop then the understanding of the dangers of direct exposure. The plaintiff argued that literature “going back as far as 1913 showed the potential for disease as a result of workers bringing home toxic substances,” but which did not specifically address asbestos. Id. at ¶ 25. In Martin v. Cincinnati Gas & Electric Co., 561 F. 3d 439 (6th Cir. 2009), the Sixth Circuit noted that “other courts have found there was no knowledge of bystander exposure in the asbestos industry in the 1950’s,” and found that the “first studies of bystander exposure were not published until 1965.” Martin, 561 F.3d at 445. Likewise, the Fourteenth District Court of Appeals of Texas found, in a 2007 case, that “the risk of ‘take home’ asbestos exposure was, in all likelihood, not foreseeable by defendant while [the plaintiff] was working at defendant’s premises from 1954 to 1965.” In re Certified Question from the Fourteenth District Court of Appeals of Texas, 740 N.W.2d 206, 218 (2007). Studies on nonoccupational asbestos exposure were also not first published until 1965. Alcoa, Inc. v. Behringer, 235 S.W.3d 456, 461 (Tex. App. 2007). In Holmes, William Dyson, an industrial hygienist who testified at trial on behalf of the defendants, said that he had found only a 1960 article by Dr. J.C. Wagner that discussed mesothelioma that allegedly resulted from a worker who was directly exposed bringing home asbestos fibers, resulting in his family’s exposure. Holmes, 2012 IL App (4th) 100462, ¶ 12. Even the plaintiff’s own expert admitted at trial that the first epidemiological study “showing an association between disease and asbestos fibers brought home from the workplace” was presented and published in October 1964. The court’s analysis, therefore, came to hinge upon what was known about the likelihood of injury from secondary, non-occupational exposure to asbestos during the pertinent time. The court ultimately found that the defendants did not owe a duty to Jean Holmes. The likelihood of injury from secondary exposure was simply too abstract of a theory at the time her husband worked with and around asbestos products for the defendants to have realistically anticipated the possibility of injury to a worker’s immediate family. Even if the requisite relationship did exist between defendants and Jean Holmes, “we would find no duty existed because of the lack of foreseeability in this case.” Id. at ¶ 24. The court wanted something more in order to establish that the defendants owed a duty to plaintiff. “To show the injury was reasonably foreseeable here, plaintiff had to establish that when decedent’s husband worked at Unarco from 1962 to 1963, it was reasonably foreseeable asbestos affixed to a worker’s clothes during work would be carried home and released at levels that would cause an asbestos-related disease in a household member.” Id. (emphasis added). In other words, foreseeability had to be based upon knowledge during the pertinent time period, and the plaintiff was not able to demonstrate this knowledge. J-8 C. Why These Cases Are Important Certainly asbestos defendants had been hoping the court would issue a definitive ruling shutting the door on most “take home” claims forever. That did not occur, and as a result defendants continue to receive claims arising from “take home” based theories. Nevertheless, the court does leave open the ability of a defendant to develop a defense theory hinged to the factual circumstances of a given case surrounding foreseeability. Perhaps an even more interesting question is how Illinois courts might extend the duty and foreseeability based reasoning to products liability cases not involving asbestos. In deciding these issues it appears the answers will be tied more closely to the concept of foreseeability under a given set of facts than to bright lines centered on the relationship status of the parties. III. THE LEARNED INTERMEDIARY DOCTRINE Successful negligence actions require that the defendant owes the plaintiff a duty, breaches the duty, and that the breach proximately causes plaintiff’s injury. However, application of these requirements is rarely so straightforward. One area that has been subject to significant changes of late is the analysis of the requisite duty and the “learned intermediary doctrine.” “[U]nder the learned intermediary doctrine, the duty to warn of the side effects of a drug is owed by the manufacturer to the patient’s physician, not the patient.” Hernandez v. Schering Corp., 2011 IL App (1st) 093306, ¶ 27; see also Wendell v. Johnson & Johnson, No. C 09-04124 CW, 2011 WL 6291792, *6 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 15, 2011). By refusing to impose upon manufacturers a direct duty to warn patients, courts recognize that receipt of highly technical health information from more than one source is more likely to confuse a patient than inform a patient. Courts also recognize that while manufacturers specialize in making and marketing safe and effective drugs, doctors specialize in discussing treatment options with patients. Therefore, manufacturers have a duty to convey information regarding treatment risk to doctors, who, using their “medical judgment,” have a duty to inform patients. A. Wendell v. Johnson & Johnson In Wendell v. Johnson & Johnson, a recent case which came out of the Northern District of California, the plaintiffs sued pharmaceutical companies on behalf of their son, Maxx, who died from hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in December 2007. Wendell, 2011 WL 6291792 at *5. The plaintiffs claimed that the defendant pharmaceutical manufacturers “failed adequately to warn about certain risks posed by their products, specifically two prescription drugs: Humira and mercaptopurine (6-MP). . . .” Id. at *1. Summary judgment was granted to the defendants because there was no showing that different warnings would have resulted in other or different courses of treatment. J-9 In 1998, Maxx was diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and was treated by Dr. Edward Rich, a pediatric gastroenterologist. Dr. Rich tried a series of drugs and drug combinations in treating Maxx, including Prednisone and 6-MP. Approximately three years into treatment, Dr. Rich began giving Maxx Remicade with the goal of weaning him off of steroids. “Dr. Rich considered Remicade . . . as part of a class of anti-tumor necrosis factor drugs, also known as ‘anti-TNF drugs’ and ‘TNF inhibitors.’” Id. at *2. Maxx took his last dose of Remicade in March of 2006. Id. at *3. After a period of good health, he relapsed in November of 2006, and began a regimen of Humira in combination with 6-MP. A rheumatologist at Dr. Rich’s hospital had to prescribe the Humira, as it was placed under limited release by the hospital’s formulary. Then, in July of 2007, Maxx was diagnosed with lymphoma, a disease that resulted in his death less than six months later. Id. at *5. Predictably, much of the trial focused on what drug warnings were issued, and by whom. “Dr. Rich testified that it was not his ‘regular practice to look at drug labeling.’ He received information on medications from multiple sources, including meetings, other professionals in the field, articles and occasional meetings with drug representatives.” Id. at *1. He also stated that, when he did read drug labeling, it was part of his decision-making process. Id. Also germane to plaintiffs’ argument was that in May 2006, when the Food and Drug Administration approved Remicade for treatment of pediatric Crohn’s disease, they required inclusion of a “black box warning” which read, RARE POSTMARKETING CASES OF HEPATOSPLENIC T-CELL LYMPHOMA HAVE BEEN REPORTED IN ADOLESCENT AND YOUNG ADULT PATIENTS WITH CROHN’S DISEASE TREATED WITH REMICADE. THIS TYPE OF T-CELL LYMPHOMA HAS A VERY AGGRESSIVE DISEASE COURSE AND IS USUALLY FATAL. ALL OF THESE HEPATOSPLENIC T-CELL LYMPHOMAS WITH REMICADE HAVE OCCURRED IN PATIENTS ON CONCOMITANT TREATMENT WITH AZATHIOPRINE OR 6MERCAPTOPURINE. Id. at *3. Dr. Rich testified that, when he prescribed 6-MP, he was aware of a medical paper reporting the occurrence of lymphoma in adults taking the drug, at a rate of approximately 1 percent. Id. at *2. He later became aware of a study that showed occurrence of malignancies at approximately the same rate in patients using Remicade, but the Physicians’ Desk Reference stated that these rates of incident were similar to the general population. At this time, Dr. Rich was aware of no studies that combined exposure to 6-MP and Remicade. All of this did have an effect on how Dr. Rich treated Maxx. Dr. Rich considered the findings of the studies to be “’significant,’ prompting him to warn patients of a ‘small but non-zero increased risk of serious infections or malignancies’ when discussing 6-MP treatment with patients. Dr. Rich testified that he may or may not have included the word ‘lymphoma’ when providing the warning.” Id. He also testified that some of these conversations may not have been documented. Further, Dr. Rich claimed that he avoided prescribing Remicade as a result of J-10 the black box warning that was included with the product, but he did not recall a similar warning with Humira. Id. at *4. For their part, Maxx’s parents testified that they had not known about the black box warning, and Dr. Rich informed them only that taking Humira would be more convenient for their son. Id. at *5. “A plaintiff asserting causes of action for failure to warn must prove not only that no warning was provided or that the warning was inadequate, but also that the inadequacy or absence of a warning caused the plaintiff’s injury.” Id. at *6. As such, California law grants summary judgment if “stronger warnings would not have altered the conduct of the prescribing physician.” Motus v. Pfizer Inc., 358 F.3d 659, 661 (9th Cir. 2004). That is because under these circumstances, the causal connection between the representations or omissions and the injury could not be established. Wendell, 2011 WL 6291792, at *5. Here, Dr. Rich testified that he sometimes read warnings when working with new drugs, or new uses for drugs. Id. at *6. In fact, Humira was a relatively new drug for treating IBD when plaintiffs’ son was prescribed the drug for his condition. However, even if Dr. Rich would have read each of the warnings available for Humira and 6-MP, summary judgment was still warranted in favor of defendants, as he prescribed the drug even knowing the heightened risk of malignancy. The evidence was insufficient to establish that these warnings would have changed the course of Maxx’s treatment under Dr. Rich. Though the doctor spoke with his patients about the “nonzero increased risk” associated with the drug, he did not stop prescribing the regimen. Id. B. Hernandez v. Schering Corp. Hernandez v. Schering Corp., 2011 IL App (1st) 093306, a learned intermediary case from Illinois, also contributed to this evolving field this year. Here, Mr. Hernandez sued the makers of PEGIntron, a drug used in the treatment of hepatitis C for injuries to his optic nerve and loss of vision resulting from his use of the medication. Hernandez, 2011 IL App (1st) 093306, ¶¶ 1-2. The Illinois court also upheld the fundamentals of the learned intermediary doctrine, finding that by offering classes to hepatitis C patients on the side effects associated with the drug, manufacturers did not forego the protection offered by the learned intermediary doctrine, and therefore did not assume a physician’s duty to warn patients of the side effects resulting from use. In December 2001, after testing positive for hepatitis C, Hernandez began seeing Dr. Suleiman Hindi, a physician specializing in diseases of the liver. Dr. Hindi recommended a drug combination known as PEG-Intron/Rebetol, which included an interferon called Pegylated and Rebetol. Hernandez began taking it in August of 2002. Approximately one month later, he had an episode in which he vomited and his vision became blurred, and his eyesight did not recover. After four days, Hernandez went to an emergency room, where it was found that he sustained damage to his optic nerve as a result of taking the medication. Id. The result was permanent vision loss. J-11 “As part of the medication regime, Dr. Hindi also expected his patients to attend an educational class sponsored by [drug maker] Schering. The class was an additional way to instruct patients how to use the medication and about any possible side effects. Dr. Hindi’s nurse would arrange for the classes when there were enough patients for a class to be held.” Id. at ¶ 7. The class made no mention of side effects associated with vision impairment, but did include some discussion on the topic in reading materials that were passed out. At the conclusion of the class, the nurseinstructor encouraged patients to follow up with their doctors regarding side effects. While other drugs were available that offered similar benefits, Dr. Hindi was more comfortable with this combination because of its more extensive history of success. Still, he acknowledged that “as a physician prescribing medication, the standard of care required him to inform patients as to the potential side effects of the medication. He did not believe that Schering’s class relieved him of his duty to provide information as to the side effects of the medication.” Id. at ¶ 8. However, Dr. Hindi was not aware of any vision related side effects. The Hernandez court’s analysis again touched upon the fact that in order for negligence to be found, there must have been a duty owed by the defendant to the plaintiff. This duty can be voluntarily undertaken, in which case it binds the defendant just the same as in any other case. The plaintiffs in this case contend that the drug manufacturer undertook a voluntary duty to warn by holding classes on the drugs’ side effects. They rely heavily on the Restatement (Second) of Torts, which states that [o]ne who undertakes, gratuitously or for consideration, to render services to another which he should recognize as necessary for the protection of a third person or his things, is subject to liability to the third person for physical harm resulting from his failure to exercise reasonable care to protect his undertaking, if (a) his failure to exercise reasonable care increases the risk of such harm, or (b) he has undertaken to perform a duty owed by another to the third person, or (c) the harm is suffered because of reliance of the other or the third person upon the undertaking. Id. at ¶ 26. The court held that the learned intermediary doctrine still served to protect the drug manufacturers from liability to the plaintiff, despite the fact that they voluntarily undertook the responsibility of providing classes on the possible side effects of one of their drugs. This is because Dr. Hindi accepted responsibility for informing his patients about the possible side effects. One amicus curiae brief submitted in this case urged the court to find that an exception to the learned intermediary doctrine where “a manufacturer and seller of a drug replaces the patient’s physician as the primary provider of information as to the risks and benefits of a drug. However, such an exception would not apply here as this case does not involve direct-toconsumer advertising.” Id. at ¶ 35. J-12 C. A Continued Strengthening of Protections for Drug Manufacturers The learned intermediary doctrine is a very important protection offered to drug manufacturers. In a highly regulated field such as medicine, courts continue to recognize that doctors are in the best position to guide their patients through the often complicated process of obtaining treatment for a serious illness. While courts appear to maintain a serious and stringent obligation on the part of drug companies to inform health care providers of the risks associated with each drug, this obligation is not always owed directly from the manufacturer to the patient. A properly informed doctor can break the causal chain between the manufacturer and the patient. To have found that such a duty exists would have seriously complicated both the patient’s decisions in obtaining treatment, and a doctor’s role guiding a patient through an illness. By upholding a strong learned intermediary rule, courts recognize that drug manufacturers are rarely in a better position to communicate with patients than are doctors. Moreover, these cases allow manufacturers to continue to offer supplemental classes on their drugs, including benefits and side effects, without fearing a disruption to the learned intermediary doctrine. From the standpoint of a medical care provider, they must continue to meet their heavy obligation of ensuring that patients are adequately informed. Physicians are less likely to implement successfully a legal defense that rests upon shifting that burden to drug manufacturers. Doing so would require proof that the patient’s harm was the result, not of the doctor’s insufficient warning to the patient, but instead the manufacturer’s insufficient warning to the doctor. This would encompass a more complex theory associated with FDA labeling compliance, and therefore might be feasible only under limited circumstances. J-13 Michael D. Schag - Partner Mike is a partner at Heyl Royster's Edwardsville office focusing his practice in toxic tort, commercial, insurance litigation, and government contracts law. He also handles cases in the firm’s Chicago office. He is experienced in jury trials, appellate practice, administrative/regulatory litigation, and alternative dispute resolution. He has handled cases entailing products liability, mass tort, commercial contract, government contract and insurance law. "10 Principles for Receiving High-Quality Legal Services," Contract Mgmt (2005) "The Consequences of Mutually Mistaken Facts in Contracting," Contract Mgmt (2005) "Developing Basic Trial Skills," The Civil Litigator (2004) Public Speaking “Issues of Justice and Dignity in the Law” John Marshall University Law School (2011) “Mortgage Foreclosures: The Meltdown Continues” Illinois Institute of Continuing Legal Education (2010) “Servicemembers Civil Relief Act” Southern Illinois University (2009) “Business Implications of Servicemembers Civil Relief Act” Illinois State Bar Association (2006-2008) Mike is a career Air Force Reserve officer holding the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He is a Judge Advocate and serves on a headquarters legal staff in Air Mobility Command at Scott Air Force Base. He is a trial advocacy instructor and sits as an administrative hearing officer. He was recently awarded his fifth Meritorious Service Medal for his work as a JAG lawyer. As an Adjunct Professor for Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University for 10 years, Mike taught over 25 graduate and undergraduate courses in insurance, environmental, labor and employment, business, and aviation law. During law school, Mike was a Merit Scholar and Articles Editor of the Law Review. Professional Associations National Contract Management Association: Board of Directors 2003-2004 American Bar Association, Litigation and Public Contracts Sections Illinois State Bar Association Significant Cases Ridenour v. Kaiser-Hill Co., 397 F.3d 925 (10th Cir. 2005) - Successful defense of government contractor in False Claims Act appeal averting revelation of classified information and adopting the Sequoia standard of review. Court Admissions State Courts of Illinois and Colorado United States Court of Federal Claims United States District Court, District of Colorado United States District, Southern District of Illinois United States Air Force Court of Criminal Appeals United States Court of Appeals, Armed Forces United States Court of Appeals, Federal Circuit United States Court of Appeals, Tenth Circuit Supreme Court of the United States Transactions Serves as an arbitrator, either at the request of the insurer or insured, at arbitrations involving insurance claims. Publications Servicemember and Veterans Rights, co-author, Matthew Bender (2011) Co-author, "Servicemembers Civil Relief Act," chapter in Military Service and the Law, Illinois Institute for Continuing Legal Education (2009) "Finding Your Way Around the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act," Illinois Bar Journal (2007) "The Dynamics of State and Local Protest Litigation," Contract Mgmt (2006) Education Juris Doctor (Cum Laude), Oklahoma City University School of Law, 1994 Bachelor of Science-Business Administration, University of Illinois, 1989 J-14 Learn more about our speakers at www.heylroyster.com