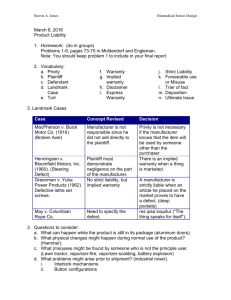

0706prod liab

advertisement

ReedSmith Partnering With Our Clients Product Liability Update June 2007 Volume III, Number 5 Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp.: Death of the ‘Simple’ Product Exception to the Application of the RiskUtility Test in Strict Liability Design Defect Cases? By Junga Park Kim and Monica Choi Arredondo While product liability cases might involve the most sophisticated cutting-edge products, they also can involve the simplest, and cases involving simple products— like a ladder or a knife—sometimes present the most conceptually challenging legal issues. Should a plaintiff be able to recover, for example, if he claims a design defect in a knife caused him to suffer a cut? There are two standard measures of whether a product has a defect in its design—the risk-utility (or risk-benefit) test and the consumer-expectations test—and in a rational system, both should lead to the denial of recovery in most cases where a knife results in a cut. After all, a knife is without utility unless it poses some cutting risk, and consumers ordinarily expect that cuts will occur even with normal, careful knife use. New York London CHICAGO PARIS Los Angeles Washington, D.C. San Francisco Philadelphia Pittsburgh Oakland MUNICH abu dhabi Princeton N. VirginiA Wilmington BIRMINGHAM dubai Century City Richmond greece r e e d s m i t h . c o m But the two tests for design defect are not entirely congruent, and the differences between them can have profound implications for manufacturers in litigation. In the pioneer decision, Barker v. Lull Engineering Co., 20 Cal.3d 413, 427-28, (1978), the California Supreme Court explained that “at a minimum a product must meet ordinary consumer expectations as to safety to avoid being found defective.” ­Barker, 20 Cal.3d at 426 n. 7. At the same time, the court cautioned that the expectations of the ordinary consumer could not be “the exclusive yardstick” for testing design defect for consumer-protection reasons, given that consumers often might not know what to expect or how safe a product could be made. Id. at 430. Subsequent cases have refined the issue in California, recognizing that the consumer-expectations test makes sense only for products that are both simple and familiar, such that “the everyday experience of the product’s users permits a conclusion that the product’s design violated minimum safety assumptions.” Soule v. General Motors Corp., 8 Cal.4th 548, 567 (1994). For more complex products, the appropriate design defect test is the risk-utility test, in which “the risks and benefits of a challenged design must be carefully balanced whenever the issue of design defect goes beyond the common experience of the product’s users.” Id. A court’s ruling that one or the other test must apply can be outcome-determinative. The consumer-expectations test usually involves little more than the jury’s instinct about what an ordinary consumer might expect of a product’s safety, while the risk-utility test usually involves competing experts and detailed evidence about (continued on page 2) ReedSmith “Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp.: Death of the ‘Simple’ Product Exception…?” – cont’d from page 1 feasible alternative designs, and an emphasis on the beneficial attributes of the product design and the safety trade-offs made to secure those benefits. At the same time, a product’s open and obvious risk may readily fit within the consumer-expectations test paradigm, fitting comfortably within a juror’s sense of who bears responsibility for patent danger, while under the riskutility test, the open and obvious nature of a danger may have little impact on an assessment of whether the design served little benefit, or whether risk could have been minimized with a different safety feature. Until earlier this year, Illinois was among the last states to recognize an exception to the application of the risk utility test for “simple” products with “open and obvious dangers” in strict liability design defect cases. Until earlier this year, Illinois was among the last states to recognize an exception to the application of the riskutility test for “simple” products with “open and obvious dangers” in strict liability design defect cases. Under this exception, lower Illinois courts had concluded that where a simple product carried an open and obvious danger, only the consumer-expectations test could be used. Frequently, the result was that juries would conclude that ordinary consumers would appreciate the open and obvious nature of the risk, making the product design defectfree. But earlier this year in Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp., 864 N.E.2d 249 (Ill. 2007), the Illinois Supreme Court rejected this theory, concluding that the risk-utility test had application even for simple products, and that open and obvious nature of a danger could be just one of many factors to be weighed by that test. Id. at 260. Like most product liability decisions, the Calles decision was grounded in policy reasons. The court believed that limiting the test for design defects for simple products to the consumerexpectations test would essentially 2 absolve manufacturers from liability in situations where reasonable and feasible safer designs existed, but the manufacturer declined to incorporate them because it knew it would not be held liable, thereby discouraging product improvements that could easily and cost-effectively alleviate the product danger. At the same time, it believed a per se rule would frustrate the policy of preventing future harm—the heart of strict products liability. Id. Origins of the “Simple” Product With an “Open and Obvious Danger” Rule in Illinois In Illinois, the simple product exception to the application of the riskutility test in design defect cases was first developed in Scoby v. Vulcan-Hart Corp., 569 N.E.2d 1147 (1991). In Scoby, a restaurant worker was injured while working in the kitchen, where he slipped, submerging his arm in hot oil in an open deep-fat fryer. The worker sued the fryer manufacturer, alleging a design defect, and argued that it was liable under the risk-utility test because additional safety features like a cover could have prevented his accident. Id. at 1148–49. Noting that hot oil in a fryer was an open and obvious danger and that, for efficient kitchen operation, it was often necessary to keep a lid off the fryer, the Scoby court concluded: We do not deem that…all manufacturers…should be subject to liability depending upon a trier of fact’s balancing under [the riskutility] test…. Somewhere, a line must be drawn beyond which the danger-utility test cannot be applied. Considering not only the obvious nature of any danger here but, also, the simple nature of the mechanism involved, we conclude the circuit court properly applied Product Liability Update only the consumer-user contemplation test. Id. at 1151 (emphasis added). Subsequently, several Illinois courts (including a number of federal courts in diversity cases) followed Scoby, finding the product or injury mechanics at issue so simple, and the alleged danger so open and obvious, that the risk-utility test was deemed superfluous in determining whether a design defect existed. See, e.g., Haddix v. Playtex. Fam. Prods. Corp., 138 F.3d 681, 685 (7th Cir. 1998) (applying Illinois law) (tampon deemed simple); Todd v. Societe Bic, S.A., 21 F.3d 1042 (7th Cir. 1994) (cigarette lighter deemed simple). In the case of simple products containing open and obvious dangers, the fact finder would almost always find that the product worked exactly as intended and had no design defect. See, e.g., Todd, 21 F.3d at 1407, 1412 (disposable lighter worked exactly as manufacturer intended by producing a flame). Not surprisingly, after Scoby, manufacturers sued in Illinois routinely argued that their products were simple and the alleged defect an open and obvious danger, while plaintiffs took to arguing that the risk-utility test should be used instead. See, e.g., Miller v. Rinker Boat Co., 815 N.E.2d 1219 (2004). In other jurisdictions, the opposite is often true, with plaintiffs advocating the use of the malleable consumer expectations test and manufacturers advocating the use of the more rigorous and expert-dependent risk-utility test. See Henderson & Twerski, Consumer Expectations’ Last Hope, 103 Colum. L. Rev. 1791, 1792 (Nov. 2003) (“The consumer expectations test as it is currently advocated by…most of the plaintiffs’ bar is an unprincipled, intellectually bankrupt approach to design-based liability that only a proponent of unrestricted liability could knowingly embrace.”). Scoby did not, however, receive universal acceptance in Illinois. Over the years, several decisions distinguished Scoby on its facts, and concluded other products were not simple. See, e.g., Hansen v. Baxter Healthcare Corp., 764 N.E.2d 35, 45-46 (Ill. 2002) (IV catheter connector not simple); Miller, 815 N.E.2d at 1232-33 (Ill. Ct. App. 2004) (boat motor not simple); Mele v. Howmedica, Inc., 808 N.E.2d 1026, 1041 (Ill. Ct. App. 2004) (artificial hip implant not simple). The issue, however, remained open. While the Illinois Supreme Court had made references to the Scoby case in prior decisions, it never had the opportunity to squarely address the validity of the simple product exception. See Blue v. Envtl. Eng’g, Inc., 828 NE.2d 1128 (2005) (strict liability design defect claim not at issue); Hansen, 764 NE.2d at 46 (finding Scoby inapposite because IV catheter connector was not simple). Indeed, in Lamkin v. Towner, 563 NE.2d 449, 530 (1990), the Illinois Supreme Court applied both the consumer-expectations and the riskutility tests in determining the manufacturer’s liability for strict liability design defect, though the case involved a simple window screen. The Diminishing Vitality of the Open and Obvious Rule When the Illinois Supreme Court finally squarely addressed the question of whether simple products with open and obvious dangers must always (continued on page 4) Would You Like to Receive Future Issues of Product Liability Update by E-mail? We would be happy to send Product Liability Update to you as an Adobe A ­ crobat® file. Please provide your e-mail address and any mailing updates b ­ elow, and send the information to Jill Himelfarb by mail, phone, fax or e‑mail. Jill Himelfarb · Reed Smith LLP 1301 K Street, N.W. – East Tower · Washington, DC 20005 Phone: 202.414.9454 · Fax: 202.414.9299 · jhimelfarb@reedsmith.com ___________________________________________________________________ Name ___________________________________________________________________ Company ___________________________________________________________________ Title ___________________________________________________________________ Address ___________________________________ _ _________ __________________ City State Zip/Postal Code ___________________________________________________________________ Phone ___________________________________________________________________ E-mail 3 ReedSmith “Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp.: Death of the ‘Simple’ Product Exception…?” – cont’d from page 3 be judged using the consumer expectations test in Calles, it framed the issue in a manner that did note bode well for the defendant. It stated that Scoby’s adoption of a simple product exception was equivalent to a general rule that manufacturers are not liable for open and obvious dangers. Calles, 864 N.E.2d at 258. A majority of courts have rejected the “open and obvious” or “patent danger” rule as an absolute defense to a design defect claim. Rest. (3d) Torts: Prods. Liabl. §2, cmt. d, at 84 (1998). Instead, most courts now consider the obviousness of an alleged defect as one of many factors to consider in determining whether a product is defective in design. See, e.g., Pike v. Frank G. Hough Co., 467 P.2d 229 (Cal. 1970) (en banc); Micallef v Miehle Co., 348 N.E.2d 571, 578 (N.Y. 1976). That said, the open and obvious danger rule still has wide and continuing validity in failure-towarn cases. See, e.g., Boyce v. Gregory Poole Equip. Co., 605 S.E.2d 570 (Ga. Ct. App. 2004), review denied (open and obvious danger no longer bars design defect claims, but may bar failure-to-warn claims). Indiana, North Carolina and Virginia are among the few jurisdictions that still follow the open and obvious danger rule in design defect cases. See Coffman v. Austgen’s Elec., Inc., 437 N.E.2d 1003, 1008 (Ind. Ct. App. 1982); McCollum v. Grove Mfg. Co., 293 S.E.2d 632 (N.C. Ct. App. 1982); Marshall v. H.K. Ferguson Co., 623 F.2d 882, 886 (4th Cir. 1980) (applying Virginia law). Moreover, in those jurisdictions where the consumer-expectations test remains the sole test for determining liability in design defect cases (including Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin), the test itself often leads to a similar result regardless of express adoption of the rule. See Rest. (3d) Torts: Prods. Liab. §2, cmt. d, at 85; see also Lamke v. Futorian Corp., 709 P.2d 684, 686 (Okla. 1985) (no liability where danger posed by a lit cigarette on a sofa was obvious); Vincer v. Esther Williams All-Aluminum Swimming Pool Co., 230 N.W.2d 794, 798 (Wis. 1975) (swimming pool not defective because of presence of retractable ladder because such conditions were obvious and average consumer would have been aware of the risk of harm to small children where retractable ladder was left in a down position and child was left unsupervised). CONTR I B UTOR S TO TH I S I SSU E Monica Choi Arredondo Associate, Los Angeles 213 457 8318 mchoi@reedsmith.com Monica is a member of the firm’s Litigation Group in the Los Angeles office. She focuses her practice on commercial litigation and product liability work. Junga Park Kim Partner, Los Angeles 213 457 8009 jkim@reedsmith.com Junga’s practice involves complex product liability matters, including mass torts, and claims for unfair business practices under § 17200 and other similar statutes. Ultimately, Calles was another blow to the application of the open and obvious danger rule as a complete bar in design defect cases, albeit not an entirely surprising result given the widespread criticism by academic commentators. See Rest. (3d) Torts: Prods. Liab. §2, cmt. d, at 85 (citations omitted). Product Liability Update is published by Reed Smith to keep clients and friends informed of legal developments in product liability law. It is not intended to provide legal advice to be used in a specific fact situation. The editor of Product Liability Update is Lisa M. Baird (213.457.8036), with the firm’s Los Angeles office. “Reed Smith” refers to Reed Smith LLP, a limited liability partnership formed in the state of Delaware. ©Reed Smith LLP 2007. The business of relationships. SM 4