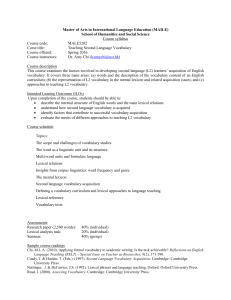

Instructed second language vocabulary learning

advertisement