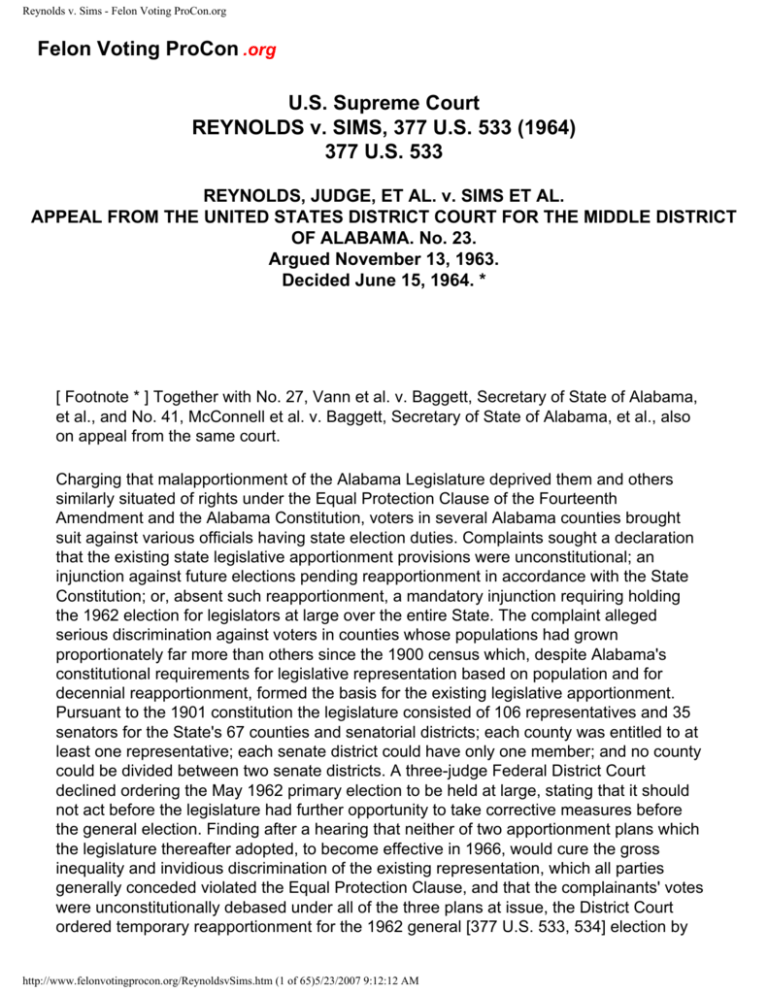

Reynolds v. Sims - Felon Voting ProCon.org

advertisement