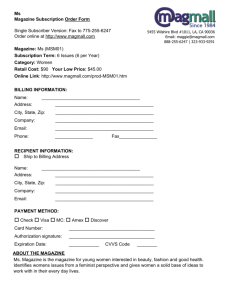

Consumers' brand experiences of magazine brands

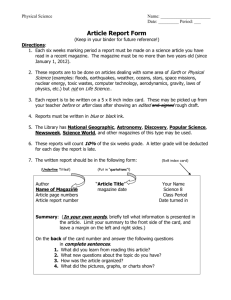

advertisement