A Queer Reading of Euripides' Bacchae

advertisement

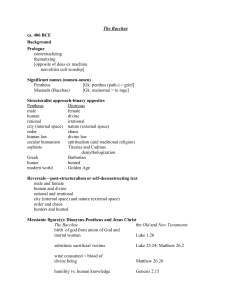

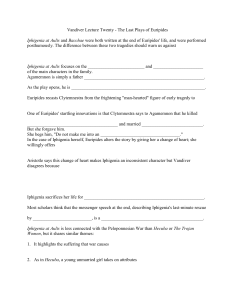

Euripides’ Bacchae A Queer Reading of Euripides’ Bacchae Natalia Theodoridou (Royal Holloway, University of London) Applying a modern critical theory to an ancient text is, by default, a problematic feat; especially when the chosen tool is queer theory, with its close affinities with gay and lesbian studies and the constant reminder that homosexuality is a recent category no more than one hundred years old.1 In such cases, the marrying of theory and artwork can result, in fact, in some very queer readings. Bearing this in mind, however, a researcher concerned with the value and vigorousness of plays on a contemporary stage, rather than the accurate reconstruction of their original production, can use the analysis of the past in order to illuminate and inform the present. Although the interest here is theatrical rather than historical, it is nevertheless important to remember that ancient Greek tragedies are the products of a specific culture and may be better understood if seen in the light of their own time. This paper investigates the various ways in which queer theory can be applied to Euripides’ Bacchae, focusing particularly on three points: the cross-dressing of the ancient Greek actors who played female roles and its effect on the creation and reception of tragedies, Dionysos’ effeminacy, and Pentheus’ famous cross-dressing scene. But before proceeding to the text, it would be useful to look at certain notions and concepts of queer theory that will accompany us throughout our reading. The term “queer” is sometimes used to describe “culturally marginal sexual self-identifications” (Jagose). Queer theory is mostly associated with gay and lesbian studies, but it also explores topics such as cross-dressing, gender ambiguity, the 1 The idea that the category “homosexual” is a social construct was introduced by Michel Foucault in his History of Sexuality. This concept has been received as a liberation from contemporary values in the study of ancient Greecethis is clearly reflected in works such as John J. Winkler’s The Constraints of Desire and David Halperin’s One Hundred Years of Homosexuality. Also of particular interest is the volume Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World, co-edited by Froma Zeitlin, John Winkler, and David Halperin. 73 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 medical construction of gender, and broadly anything that displays a gap or incoherence between sex, gender and desire. This display often assumes a very theatrical or dramatic character: performance becomes a means of exposing but also of magnifying the gap. Therefore, gender-b(l)ending also blends reality and performance, effectively deconstructing both. Despite the different ways in which they engage in the discussion about gender difference, feminist theorists since Simone de Beauvoir have consistently argued against the pre-existence of gender as a biological feature and rejected its essentiality to an individual's identity (Abrams 88-100). This line of reasoning produced a rupture in the image of the self and contributed to the deconstruction of the idea of the essential selfhood. Therefore, according to feminist thought, femininity is not an innate characteristic of female beings, and masculinity is not a natural attribute of male beings. What queer theory added to that was the idea—first formulated by Judith Butler—that gender is not only a socially constructed artifice, but a show, a masquerade, a costume that can be worn, adapted, or even torn to pieces through potentially subversive acts, such as “drag” or cross-dressing.2 According to Butler, “the acts by which gender is constituted bear similarities to performative acts within theatrical contexts” (“Performative Acts” 521). Hence, what is of interest here is the construction and deconstruction of gender through dressing and cross-dressing, as well as the theatricality of cross-dressing and cross-dressing as a theatrical performance. It has been argued that the notion of cross-dressing in the sense of “dressing in the clothes of the opposite sex” suggests that there is an original which is parodied (Raymond 218). On the contrary, Butler suggests that “[i]n imitating gender, drag 2 The idea is termed “gender performativity,” coined by Butler in her 1990 book Gender Trouble. 74 Euripides’ Bacchae implicitly reveals the imitative nature of gender itself” (Gender Trouble 187), and argues that this “elusive” original identity is “an imitation without an origin” (Gender Trouble 188). In this sense the cross-dresser who successfully attempts to “pass,” to go unnoticed as a member of another sex, incorporates the socially constructed gender, exposing what culture has made invisible: gender is taught, learnt and can be accomplished (Solomon 5). Thus, the presence of the transvestite interrupts and reconfigures the established definition of and relationship between genders, which were hitherto conceived as unchangeable and fully explored. Marjorie Garber includes ancient Greek theatre, along with Shakespearean theatre, in the category of “transvestite theatre” (39-40), because it was solely men who played the female parts of the plays. Although it would be easy to criticise this practice from a feminist perspective—attacking the female impersonation as false, biased and alien to the experience of “real” women—it is interesting to investigate the possibility that “transvestite theatre” may be an “internal critique of the forces that govern the representation of women both on stage and off” (Solomon 9), a challenge to the binary opposition between male and female, facilitated precisely by the Dionysiac context in which the performances were taking place. Dionysos, as we will see in greater detail below, was a god associated with transvestism, theatre, and the collapse or inversion of polarities such as god/beast, man/woman. Hence, it is only natural that the festival organised by the city-state in his honour was, also, a festival of inversion. Queer culture is said to consist of two more or less distinct worlds: the “flamboyant,” which includes the showy and “Almodovarian”3 world of transvestite clubs, shows, and drag queens, and the “closet,” which is secretive, withdrawn and self-contained. Maybe ancient Athenian 3 Spanish film director Pedro Almodovar is highly eloquent in conveying the essence of the “flamboyant,” especially in such films as High Heels (1991), All About My Mother (1999), and Bad Education (2004). 75 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 theatre can be seen as a mixture of these now separate “cultures”: a sort of drag show fully accepted by, and embedded in, the community. The flamboyant and the closet become one and are inseparable: at the heart of a respected institution of the city are men dressed as women, problematising and reflecting on some of the most pressing political, ideological and philosophical issues; possibly the ones also discussed at Symposia.4 Judith Butler's view of gender as a performance is very interesting when applied to actual, literal performances in which gender becomes a theatrical act: on the stage of the theatre of Dionysos, in a highly political theatre viewed mainly by men and played exclusively by male citizens, drag became not only legitimised, but part of the dominant ideology. The maleness of the actors could be seen as an instance of gender-bending, a subversive questioning of the fixity of gender (Rabinowitz). In the context of inversion that the Dionysiac cult offered, though, cross-dressing was a contained form of deviance, simultaneously challenging and supporting the perpetuation of the “normal” and the “normative.” Thus, it is rational to say that “the theatre was also a state function” (Barlow 2), in the sense that it helped purge the city of any tendencies that would be considered marginal, out of the ordinary, and, indeed, queer. What happens in Euripides’ Bacchae, however, is an inversion of this inversion: what is presented on stage is the resistance to the introduction of the cult of Dionysus to the city of Thebes and its final, violent establishment through the same forces that were unleashed during the Dionysiac festivals; the “normal,” useful queerness of the festivals is (mis)placed outside the Athenian ritual context and becomes the very mechanism which brings about the tragic fall. Euripides, here, calls 4 For more information about Symposia in Ancient Greece see Fisher. 76 Euripides’ Bacchae attention to the function of theatre within the Dionysiac cult and exposes the ambiguity of its practices. Therefore, the play is abundant in cases of genderb(l)ending: it features Dionysos, the prominent spectator of the tragedies acting in his own theatre, for himself and for the whole city to see, with special importance given to his effeminate appearance; Teiresias, who bridged (or jumped) the gap between male and female twice in his life; and a king, Pentheus, who cross-dresses under the influence of this strange god and is led to his demise as a transvestite. Apart from these “feminised males” there is also a “masculinised female” (Zeitlin 344), Agaue, played, of course, by a cross-dressed male actor. But let us begin with the case of Dionysos. Dionysos was a god inextricably linked with theatre and, therefore, with false realities, deceptive images and the representation or exaggeration of reality. He was also a god known to have an identity oscillating between extremes: he was both Theban and Asian, both Greek and barbarian, raised as a girl, dismembered by the Titans, and transformed into a bull. He also delighted in imitating newborn children, small girls and women, in appearance, dress and comportment (Bremmer 187-88). When Dionysos first appears in the Bacchae’s prologue, he announces that he is a god in disguise, a supernatural being wearing the costume of a man (Bacchae lines 4-5), and he is later straightforwardly described by Pentheus as womanish (45359). Then again, ancient spectators would also know that, in reality, Dionysos was an actor dressed up as a god who, in turn, was dressed up as an effeminate man, maybe retaining some elements of the potential cross-dressing of the actor as a woman. From the very beginning, Dionysos’ body is deceitful, an act, a performance within a performance within a performance. And, like some contemporary transgenderists, he goes beyond the one-sided femininity of a male-to-female cross-dresser (Raymond 77 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 218): he blends characteristics of both genders, creating a queer, new mixture, which matches perfectly the image of the most ambiguous of gods. Dionysos' strange body, neither male nor female, rendered almost immaterial by his perpetual imitations and transformations, cannot be bound by any prison (Bacchae 616-17). He is the physical embodiment of the deconstruction of a singular identity. Jay Michaelson suggests that “[i]n contemporary queer theory, binaries are the enemy. They […] invariably administer power to the powerful, subjecting the weak to the rule of the strong” (56); Dionysos, however, appears as a true knight of queer: he negates the normal order of things and renders the weak tragically strong. He appears to be soft but uses the typically “weak” womanliness to destroy the authoritative, masculine king and he transforms the women of Thebes into wild huntresses—and “hunting was a typically male activity” (Bremmer 193). When Dionysos enters the city, “the ground flows with milk” (Bacchae 142) as if the (mother)land were impregnated. He is surrounded by a chorus of bacchants (again, a chorus of male, cross-dressed actors), pregnant with divine madness,5 following a deviant god, a queer religion, copulating with him in the wild. In the Oxford English Dictionary, the term “queer” has a primary meaning of “odd,” “strange,” something which is “out of the ordinary,” and this is precisely what the cult of Dionysos is when it is introduced to Thebes: something queer, dangerous, which provokes forceful political action from the ones struggling to preserve the status quo and the established power relations in the city. 5 A very interesting example of the Bacchants being literally represented as pregnant women can be found in Luca Ronconi's Bacchae, presented in Epidaurus in 2004. The divine madness transcended the metaphorical level and assumed an embodied, physical presence. Moreover, the theatre was filled with a feeling of imminence: the pregnant Bacchants could start giving birth at any time, filling the orchestra with blood, placentas, and shrieking babies. Besides, “giving birththe production of human offspring the way beasts produce their owndisplays to Greek eyes, with its screams, its agony, and its delirium, the wild and animal side of femaleness” (Vernant 202). 78 Euripides’ Bacchae Charles Segal argues that “Dionysus operates as the principle that destroys differences” (234); so, the difference between himself and Pentheus is going to be gradually destroyed. Himself feminine, Dionysos is going to persuade Pentheus to dress in female attire and indirectly become one of his followers, as transvestism was inherent in Dionysiac mystic initiation (Segal 33). Dionysos, as we have seen, appears, in the beginning of the play, as a kind of god-to-human cross-dresser. Pentheus later will not only become a male-to-female transvestite but also a humanto-god cross-dresser as he will be partly identified with Dionysos. Several modern critics have proposed the idea that Pentheus’ cross-dressing is consistent with his desire for Dionysos and previously suppressed homosexual tendencies (Ormand 10-13). Eric Robertson Dodds has also argued that Pentheus’ negative reaction against the Dionysiac cult was a result of the fact that it blurred the differences of gender and class (xxvii-xxviii) and this could be approached as an instance of “homophobic panic.” However interesting these psychological interpretations may be, though, it is also useful to see how the moment when the cross-dressing begins produces a break in Pentheus’ identity and poses some significant questions regarding the representation of gender on stage. Prior to his “feminisation,” Pentheus is the “ideal” picture of masculinity: a strong king, a man in power. When he cross-dresses, however, he shows signs of what might be considered typical of “female nature,” that is, of the socially constructed image of the female gender; he is overtly concerned with his appearance, a true coquette (Bacchae 932-44), and he is willing to deploy tricks like disguising, hiding and spying – all suitable only for women and adolescents, beings partly belonging to wilderness – thus renouncing his hoplite military code which demands direct, masculine confrontation (Ormand 13). 79 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 The second alteration of Pentheus’ identity is associated with his increasing likeness to Dionysos, and the similarity between the two heroes is doubled: there is similarity in appearance, and similarity in death. When Pentheus emerges from the palace dressed as a woman, he sees double for the first time: “two suns, and a double Thebes” (Bacchae 918-19). Seeing double is a “symptom of madness […], but madness is the emblem of the feminine,” also associated with the “double consciousness that a man acquired by dressing like a woman and entering into the theatrical illusion” (Zeitlin 363). Once he is dressed as a woman, Pentheus adjusts his costume like an actor preparing for a performance (Foley 225). He embodies the double reality of a cross-dressed actor, but does so within the tragedy, thus both exposing the mechanism of female representation on-stage and drawing attention to the very origins of performative transvestism, associating it with the cross-dressing often practiced in Dionysiac cult. But the audience, in this scene, also sees double: there are two effeminate figures on stage, “carrying the same Dionysiac paraphernalia” (Foley 250). And since Pentheus is an imitation or parody of Dionysos' appearance and mixed gender, he will also share his death, or a parody thereof: “[i]t is one of the peculiarities of Greek myths that a hero(ine) is sometimes killed by a god, while at the same time being closely identified with that particular god” (Bremmer 194). This is also true for Pentheus: Dionysos’ body was torn apart by the Titans and then reconstructed by a kind deity. Pentheus is going to be dismembered by his god-maddened mother, but he is not going to be as lucky: his torn apart body is going to be “searched […] out with difficulty” (Bacchae 1299) by his grandfather and brought back on stage in pieces. Quite ironically, Pentheus wanted to decapitate Dionysos (Bacchae 241), but he was actually talking about his own fate. 80 Euripides’ Bacchae So, the power-relations between Pentheus and Dionysos have been inverted: the weak has become the strong, while both are now effeminate. Previously, the masculine king was unquestionably in power, while the effeminate stranger was the object of mockery; the ambiguous identity of the latter positioned him in the powerless end of the power continuum. Now, the transvestite, the one who was earlier fully masculine, is less powerful than the androgynous god; assuming a pseudoidentity, wearing femininity as if it were a costume, Pentheus is a powerless no-one while Dionysos’ power derives from the very fact that he bridges the gap between genders within his own identity. One of the themes explored here is the idea of womanliness as a masquerade. “Female characters were not only identified by their clothing, the clothes literally stood for the woman” (Ferris 166). In his cross-dressing, Pentheus actually wears a woman. In doing so, the king exposes his divided self (Foley 227), a fact which is very soon going to assume a tragically literal sense. The “queerness” of Dionysos’ cult has infected Pentheus, the normal-man-in-power, and turned him into a transvestite, a queer subject whose body is going to be dismembered/deconstructed in the hands of his deviant mother (another transvestite, a respectable Athenian male actor dressed as/embodying a blood-thirsty woman). Gender-bending here assumes such an extreme form that the opposite extremes reach each other and come to merge. Butler suggests that “as a strategy of survival, gender is a performance with clearly punitive consequences” (“Performative Acts” 522), which means that failure to perform one’s gender correctly results in punishment. In this instance, however, Pentheus is punished for his stubbornness in trying to preserve his ideal image of manhood and his hubris against the ambiguity which Dionysos personifies, and he is 81 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 punished precisely through the deconstruction and disruption of the apparent coherence of his masculine self. Contemporary critics such as Butler would argue that this deconstruction is possible precisely because the gendered self is not an innate or biological characteristic but a socially constructed and instructed performance. Pentheus the King is therefore merely the representation of the powerful Man, a symbolic locus of power. This representation succumbs to the irresistible force of inversion, the dismantling force of the gender-bending god, necessary for the survival and preservation of the “normal” order.6 This confirmation of “normality” through the temporary assumption of an alien identity is particularly evident in many rites of passage of classical antiquity. Especially in ancient Greek puberty rituals, young boys would often dress in women's clothes, imitating the “radical other” (Zeitlin 346) in order to secure the characteristics of the masculine adult and reject the inappropriate feminine ones by the symbolic act of dropping the female outfit. Rites of passage could be broken down into three distinct stages: community, liminality, and reintegration (Turner 94). “The second phase, ‘liminality,’ is characterized by disorientation and a breakdown of normal concepts of identity and behavioural norms” (Csapo 253). The transvestism of Pentheus can be seen as an unsuccessful or inverted rite of passage: instead of passing from the status of a boy to adulthood (to become a king, no less), he escapes his masculinity and kinghood to become a powerless boy, torn to pieces by his own mother, returning to the immaterial state of death, incorporated again by his mother, through the sparagmos, the raw-eating of his flesh (Bacchae 139); but her body is 6 The idea that a contained form of deviance (such as an institutionalised festival of inversion) has the power to establish the norm even more firmly has its roots in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s concept that ancient Greek thought was structured in polarities which had to interpenetrate at specific occasions and in carefully controlled ways so as to be kept separate for the rest of the time. See Lévi-Strauss, Vernant, Vidal-Naquet. 82 Euripides’ Bacchae now a burial place instead of a cradle of life, her womb now a tomb. Pentheus is separated from the community, reaches a liminal condition when dressed as a woman but he is not re-incorporated in the end—or he is, in a very perverted and grotesque way. The cross-dressing of Pentheus can be seen as the first stage of his sparagmos, as it seems to loosen its structures so that it will easily become “unbound,” undone and fragmented (Zeitlin 352). The cross-dressing seems to have corroded the concreteness of the male body and has lent to the masculine compactness something of the alleged fluidity and permeability that made female bodies so dangerous, so “other.” Thus, “Greek tragedy […] could […] be called the ‘misadventure of the human body’” (Zeitlin 349-50). In Euripides’ Bacchae one can witness this “misadventure” in all its magnitude: the male actors' bodies assume the appearance of masculinised women; Dionysos, a god, is bound in human form; Pentheus’ body loses its undivided identity and becomes a transvestite or, as some would have it, something in-between, a “third gender” (Rabinowitz), and is finally dismembered. What is more, this misadventure of the body is entangled in the fine nets of theatre: it becomes a spectacle. Nancy Rabinowitz talks about the cross-dressed actor as a new species, a third gender, but Pentheus becomes this third gender inside the performance, thus unconcealed by the theatrical illusion. In addition, Pentheus goes to the meeting-place of the maenads with the intention of becoming a hidden spectator, a voyeur of their mystic rites; instead, Dionysos makes a spectacle of the king in front of both the Theban and the Athenian citizens (Bacchae 854-56). “It is with theatrical weapons […] that Dionysus destroys Pentheus” (Foley 223). In this context, not only womanliness, but any gender, is exposed as a masquerade, a garb. Thus in the closing scene of Klaus-Michael Grüber's famous production of Bacchae, Pentheus’ 83 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 dismembered body is nothing more than pieces of clothing torn apart, the remains of a costume that may be sewn back together, but will never form an un-fragmented whole. In this context of spectacle and spectatorship, gender relations can be explored and may be subverted through a whole range of queer encounters between them. The volatile nature of human identity in theatrical contexts “is precisely what makes theatre the queerest art” (Solomon 2). Pentheus is the one who considers a cult of transvestism and theatre dangerous and is finally destroyed by these very mechanisms; the fate of Thebes, though, the imagined alter-ego of Athens, remains unknown. For Athens, on the other hand, the gap between gender and its performance migrates from the individual to the collective through the theatrical experience. What happens next, however, is an unanswered question: Athens has either incorporated the ambiguity of gender through the centralisation of theatre and its androgynous god or neatly tucked it in the place where it can cause the least harm. Thus, Euripides’ Bacchae can be seen as either subversive or appropriative of gender roles; and both choices would be equally legitimate. When the cross-dressed Pentheus encountered the cross-dressed actor who played Agaue, or, even more interestingly, when, in accordance with the ancient Greek theatrical rule that limited the number of actors to three, the actor who previously played the cross-dressed Pentheus appeared dressed as his mother (Damen 320), what happened, more than anything else, was that the problem of representation was put under the microscope and became a point of reflection for all the male citizens. One could say that, through its dangerous and disastrous inversion, the category of “man” was reconfigured and stabilised; someone else could say that the transvestite theatre of ancient Athens destabilised and challenged the supposed 84 Euripides’ Bacchae fixedness of gender (Butler, Gender Trouble xxv). Besides, “there is no necessary relation between drag and subversion, and […] drag may well be used in the service of both the denaturalization and reidialization of […] gender norms” (Butler, Bodies that Matter 125). Which of the two sides one focuses on is a matter of choice, or even, of agenda. 85 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 References Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 7th ed. Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 1999. Bacchae. By Euripides. Dir. Klaus Michael Grüber. Perf. Michael König. Shaubühne, Berlin. 1974. Bacchae. By Euripides. Dir. Luca Ronconi. Perf. Massimo Popolizio, Giovanni Crippa. Epidaurus, Greece. 2-3 July 2004. Barlow, Shirley. “General Introduction to the Series.” Introduction. Bacchae. By Euripides. Trans. Richard Seaford. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1996. 124. Bremmer, Jan. “Transvestite Dionysos.” Rites of Passage in Ancient Greece: Literature, Religion, Society. Ed. Mark William Padilla. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1999. 183-200. Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of "Sex." London & New York: Routledge, 1993. ---. Gender Trouble. 1990. London & New York: Routledge, 2007. ---. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal 40.4 (1988): 519-31. Csapo, Eric. “Riding the Phallus for Dionysus: Iconology, Ritual, and Gender-Role De/Construction.” Phoenix 51.3/4 (1997): 253-95. Damen, Mark. “Actor and Character in Greek Tragedy.” Theatre Journal 41.3 (1989): 316-40. Dodds, Eric Robertson. Introduction. Bacchae. By Euripides. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986. xi-lix. Ekins, Richard, and Dave King, eds. Blending Genders: Social Aspects of Crossdressing and Sex-changing. London & New York: Routledge, 1996. 86 Euripides’ Bacchae Euripides. Bacchae. Trans. Richard Seaford. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1996. Ferris, Lesley. “Introduction to Part Five: Cross-dressing and Women's Theatre.” The Routledge Reader in Gender and Performance. Ed. Lizbeth Goodman and Jane de Gay. London & New York: Routledge, 1998. 165-69. Fisher, N.R.E. “Greek Associations, Symposia, and Clubs.” Civilization of the Ancient Mediterranean: Greece and Rome. Ed. M. Grant and R. Kitzinger. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988. 1167-97. Foley, Helene. Ritual Irony: Poetry and Sacrifice in Euripides. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1985. Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. Trans. R. Hurley. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. Garber, Marjorie. Vested Interests: Cross-dressing and Cultural Anxiety. 1992. London: Penguin, 1993. Goodman, Lizbeth, and Jane de Gay, eds. The Routledge Reader in Gender and Performance. London & New York: Routledge, 1998. Grant, Michael, and Rachel Kitzinger, eds. Civilization of the Ancient Mediterranean: Greece and Rome. 3 vols. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988. Halperin, David. One Hundred Years of Homosexuality: And Other Essays on Greek Love. New York & London: Routledge, 1990. Jagose, Annamarie. “Queer Theory.” Australian Humanities Review: Queer Theory. 6 Dec. 2007 <http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/AHR/archive/Issue-Dec1996/jagose.html>. Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Mythologiques: Le cru et le cuit. Paris: Plon, 1964. 87 Platform, Vol. 3, No. 1 Michaelson, Jay. “Shatnez and Civilization: The Queer Path of the Boundary Crosser.” Tikkun Magazine (2006): 55-60. 6 Dec. 2007 <www.metatronics.net/words/michaelson-shatnez.pdf>. Ormand, Kirk. “Oedipus the Queen: Cross-gendering Without Drag.” Theatre Journal 55 (2003): 1-28. Padilla, Mark William, ed. Rites of Passage in Ancient Greece: Literature, Religion, Society. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1999. “Queer.” The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. Rabinowitz, Nancy. “How is it played? The Male Actor of Greek Tragedy: Evidence of Misogyny or Gender-Bending?” Didaskalia: Ancient Theater Today 1.6 (1995). 6 Dec. 2007 <http://www.didaskalia.net/issues/supplement1/rabinowitz.html>. Raymond, Janice. “The Politics of Transgenderism.” Blending Genders: Social Aspects of Cross-dressing and Sex-changing. Ed. Richard Ekins and Dave King. London & New York: Routledge, 1996. 215-23. Segal, Charles. Dionysiac Poetics and Euripides’ Bacchae. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982. Solomon, Alisa. Re-Dressing the Canon: Essays on Theater and Gender. London & New York: Routledge, 1997. Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. 1969. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1995. Vernant, Jean-Pierre. Mortals and Immortals: Collected Essays. Ed. Froma Zeitlin. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991. Vidal-Naquet, Pierre. Le Chasseur Noir: Formes de Pensée et Formes de Societé dans le Monde Grec. Paris: Maspero, 1981. 88 Euripides’ Bacchae Winkler, John. The Constraints of Desire: The Anthropology of Sex and Gender in Ancient Greece. New York & London: Routledge, 1990. Zeitlin, Froma. Playing the Other: Gender and Society in Classical Greek Literature. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1996. Zeitlin, Froma, John Winkler, and David Halperin, eds. Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. 89