VIEW PDF - Fordham Law Review

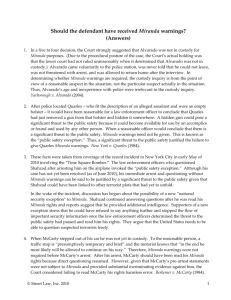

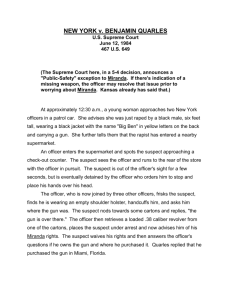

advertisement