Will Arkansas Game & Fish Commission v. United States Provide a

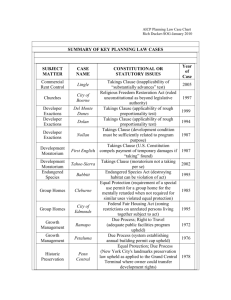

advertisement