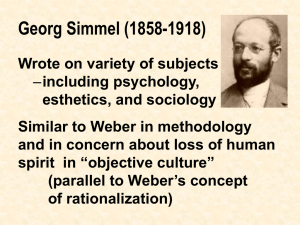

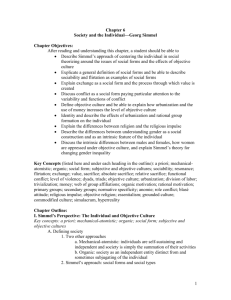

From the Iron Cage to Eichmann: German Social Theory and the

advertisement