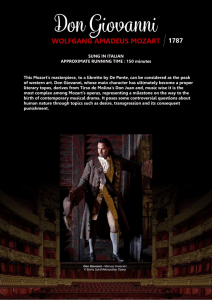

Don Giovanni's women

advertisement