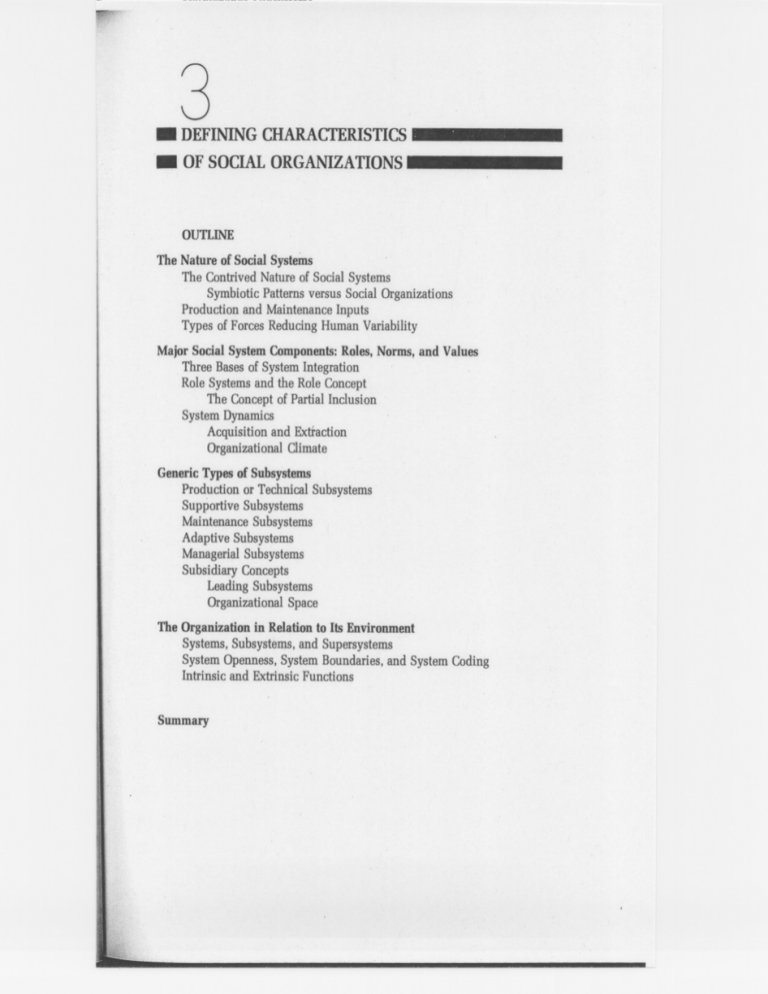

_ DEFINING CHARACfERISTICS _ OF SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS

advertisement