Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential

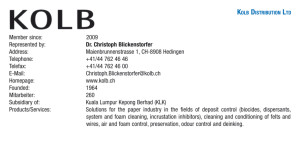

advertisement