TYPES OF EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIES: Basic Knowledge

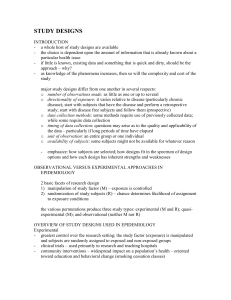

advertisement

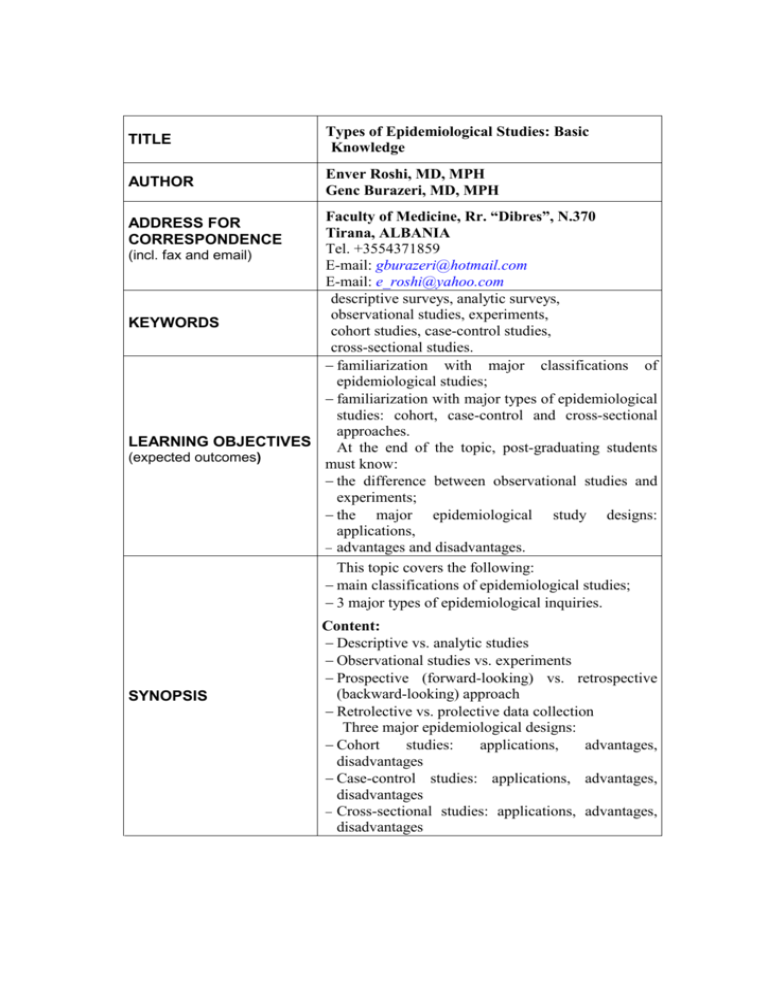

TITLE Types of Epidemiological Studies: Basic Knowledge AUTHOR Enver Roshi, MD, MPH Genc Burazeri, MD, MPH Faculty of Medicine, Rr. “Dibres”, N.370 Tirana, ALBANIA Tel. +3554371859 (incl. fax and email) E-mail: gburazeri@hotmail.com E-mail: e_roshi@yahoo.com descriptive surveys, analytic surveys, observational studies, experiments, KEYWORDS cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies. − familiarization with major classifications of epidemiological studies; − familiarization with major types of epidemiological studies: cohort, case-control and cross-sectional approaches. LEARNING OBJECTIVES At the end of the topic, post-graduating students (expected outcomes) must know: − the difference between observational studies and experiments; − the major epidemiological study designs: applications, − advantages and disadvantages. This topic covers the following: − main classifications of epidemiological studies; − 3 major types of epidemiological inquiries. ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE SYNOPSIS Content: − Descriptive vs. analytic studies − Observational studies vs. experiments − Prospective (forward-looking) vs. retrospective (backward-looking) approach − Retrolective vs. prolective data collection Three major epidemiological designs: − Cohort studies: applications, advantages, disadvantages − Case-control studies: applications, advantages, disadvantages − Cross-sectional studies: applications, advantages, disadvantages TEACHING METHODS − introductory lecture − illustrative examples of main − epidemiological study designs. SPECIFIC RECOMMENDATIONS ASSESSMENT OF STUDENTS (type of examination) take-home exercise on the applications, advantages and limitations of the main epidemiological studies. TYPES OF EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIES: Basic Knowledge Enver Roshi, MD, MPH Genc Burazeri, MD, MPH Faculty of Medicine, Rr. “Dibres”, N.370 Tirana, ALBANIA Tel. +3554371859 E-mail: gburazeri@hotmail.com E-mail: e_roshi@yahoo.com CONTENT ! ! ! ! ! Descriptive vs. analytic studies Observational studies vs. experiments Prospective (forward-looking) vs. retrospective (backward-looking) approach Retrolective vs. prolective data collection Three major epidemiological designs: o Cohort studies: applications, advantages, disadvantages o Case-control studies: applications, advantages, disadvantages o Cross-sectional studies: applications, advantages, disadvantages Basic Knowledge Epidemiological studies may deal merely with the distribution of diseases/conditions in human populations (descriptive surveys), and/or with the factors influencing the distribution and the frequency of diseases (analytic surveys: cross-sectional, casecontrol, cohort, quasi-experiment and experimental studies). Descriptive survey • Describes a situation, e.g. distribution of a disease/condition in a certain population in relation to sex, age, or other characteristics. Analytical survey (explanatory study) • Tests hypotheses • Looks for associations based on: a) groups (ecological/correlation studies, trend studies); b) based on individuals (cross-sectional, case-control, cohort, experiments and quasi-experiments). This is the most classical way of classifying the epidemiological inquiries. However, this classification has little practical value in itself, since the same study could be both descriptive and analytic or, in principle, all studies could be regarded as analytic (e.g. the distribution of a certain condition by sex or age could be regarded as a sort of implicit analysis rather than just description of the observed facts). The most important way of classifying the epidemiological studies is the one which accounts for the role/control of the researcher over the study. According to this, a major distinction is being made of: a) observational studies, and b) experiments. Observational studies • The investigator observes the occurrence of the condition/disease in population groups that have assigned themselves to a certain exposure. • Often most practical and feasible to conduct. • Carried out in more natural settings – representative of the target population. • Often, there is little control over the study situation – results are susceptible to distorting influences. Experimental approach • The most powerful study design for testing ethiological hypothesis. • The investigator exercises control over the allocation of exposure, its associated factors and observation of the outcome. • For obvious ethical and practical reasons, the possibilities of conducting experiments in human populations are very limited. Direction of Study Question According to the direction of inquiry, epidemiological studies are classified as follows: Prospective (forward-looking) approach – in which (disease free) people who are exposed and non exposed are followed up and compared with respect to the subsequent development of the disease/outcome under study. Retrospective (backward-looking) approach – in which people with the disease are compared with people without the disease, to determine whether they differ in their past exposure to the (hypothesized) causative factor. Non-Directional Design – the investigator observes simultaneously the exposure and disease status in the study population. Ambispective Design – one primary variable/factor is measured prospectively and the other one retrospectively, or one primary variable/factor is measured both prospectively and retrospectively. Direction of Data Collection Retrolective – data collected before the study design (not necessarily for the purpose of the actual study). Prolective – data collected after study design (for the purpose of the actual study). Three major types of epidemiological studies 1) Cohort Studies. The design of a cohort study is sketched below: Disease Exposed Population No disease People without the disease “at risk” Disease Not exposed No disease • The essence of cohort studies is the identification of a group of subjects about whom certain exposure information is collected. The group is then followed up in time to ascertain the occurrence of disease/condition of interest. • For each individual prior exposure can be related to subsequent disease experience. • Since the first requirement of such studies is the identification of the individuals forming the study group – COHORT, prospective or longitudinal studies are usually referred to as cohort studies. Advantages of cohort studies 1. Measure incidence and thus permit direct estimation of risk of disease. 2. Do not rely on memory for information about exposure status, hence avoid bias due to selective recall. 3. Since cohort studies begin with people free of disease, potential bias due to selective survival is eliminated. 4. Cohort studies provide a logical approach to studies of causation or effects of treatment. 5. Cohort approach can yield information on associations of exposure with several diseases. Disadvantages of cohort studies 1. Require large samples to yield the same number of cases that could be studied more efficiently in a case-control study. 2. Particularly inefficient for studies of rare diseases. 3. Logistically difficult – long follow-up period, often serious attrition to study subjects. 4. Direct observation of participants may cause changes in health behavior. 5. Possible bias in ascertainment of disease due to changes over time in criteria and methods. 6. Very costly. An alternative strategy to the costly and time consuming prospective cohort design is the historical cohort study. A cohort is identified (enumerated) as of some historical point in time and is then followed over past time to the present. Disease rates and relative risk (RR) can be derived from this type of study as well. The retrospective (historical) cohort approach is particularly amenable to the study of exposure-disease relationship for which the exposure group is unusual in some way, e.g. many occupational or environment exposure-disease relationships. 2) Case-Control Studies. The design of a case-control study is sketched below: Exposed Cases Not exposed Population Exposed Not exposed TIME DIRECTION OF INQUIRY Controls The case-control study begins with a group of cases of a specific disease. This (the disease) is the starting point of the study, unlike cohort studies where the interest is in drawing a contrast between exposed and non-exposed subjects. So, the case-control approach is directed at the prior exposures, which caused the disease and thus proceeds from effect (outcome) to cause (exposure). Advantages of case-control studies 1. Highly informative compared to other designs: several exposures or potential causal agents can be examined. 2. Efficient designs (low cost per study) primarily because few subjects are needed to obtain stable estimate of RR. 3. Particularly appropriate for studies of rare diseases (e.g. a case-control study with 100 cases of a disease having an annual incidence of 1/1000. A cohort design for this disease would require 1000 persons to be followed up for 100 years or 10000 persons to be followed up for 10 years in order to yield the same number of cases). Disadvantages of case-control studies 1. The absolute frequency of a disease can not be determined. No counts are made of population at-risk, thus there are no denominators available to obtain the incidence rates. Lacking absolute risks, it’s not possible to compare disease rates among different studies, nor is it possible to estimate the attributable risk. 2. Particularly subject to bias: selection bias in choosing controls and recall bias (cases may recall better prior exposures than controls). 3. “Philosophically” difficult to interpret: the antecedent-consequent relationship (exposure-outcome) is subject to considerable uncertainty. 3) Cross-Sectional Studies. The design of a cross-sectional study is sketched below: Population Information on both exposure and disease Exposed and have the disease Exposed, do not have the disease Not exposed, have the disease Not exposed, do not have the disease Cross-sectional design is referred to as non-directional or one point in time survey, where data is collected on both outcome and exposure status of the individuals under study. Such studies are useful to describe characteristics of study population and can generate new ethiological hypothesis. This study design involves disease prevalence. Cross-sectional studies can evaluate the impact of changes in health services during an intervening period. This can be accomplished by conducting a cross-sectional study twice: before and after the intervention. Advantages of cross-sectional studies 1. Describe the distribution of both exposure and outcome in a population (particularly useful for studying frequent outcomes of long duration). 2. Provide estimates of the magnitude of a disease problem in a community, which might be very important for planning of health services. 3. Compared with other studies are relatively quick and inexpensive. Often, involve only one-time survey. 4. Largely applicable: provision of health care services as well as generation of ethiological hypothesis. Disadvantages of cross-sectional studies 1. Do not measure risk, because this would require incidence data. 2. Can not determine cause-effect relationship. 3. Current exposure status may be due to changes that have occurred as a result of the disease rather than having led to the disease. 4. Diseases of short duration may be missed. Thus, cross-sectional studies are best applied to the study of chronic or persistent conditions. References/Recommended Readings 1. Gordis L. (1996). Epidemiology. W.B.Sounders Company, Philadelphia. 2. Abramson JH, Abramson ZH. (1999). Survey methods in community medicine. Churchill Livingstone, New York. 3. Lilienfeld AM, Lilienfeld DE. (1980). Foundations of epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York. 4. MacMahon B, Pugh TF. (1970). Epidemiology: principles and methods. Little, Brown, Boston, Massachusetts. 5. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. (1992). Epidemiologic research: principles and quantitative methods. Lifetime Learning Publications, Belmont, California. 6. Abramson JH, Feinleib M, Detels R, Greenberg RS, Ibrahim MA. Oxford Textbook of Public Health. (1985) vol 3: investigative methods in public health. Oxford University Press, Oxford.