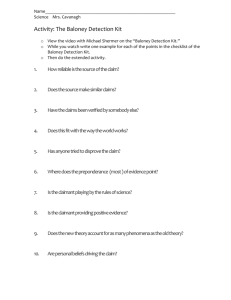

Acton_Biology_files/Baloney Detection Kit

advertisement

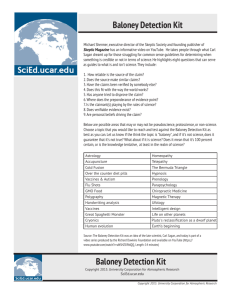

Baloney Detection Kit SAGAN'S TEN TOOLS FOR BALONEY DETECTION In The Demon Haunted World Carl Sagan suggested some "tools for skeptical thinking:' these include: 1. Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the "facts:' 2. Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view. 3. Arguments from authority carry little weight-"authorities" have made mistakes in the past. They will do so again in the future. Perhaps a better way to say it is that in science there are no authorities; at most, there are experts. 4. Spin more than one hypothesis. If there's something to be explained, think of all the different ways in which it could be explained. Then think of tests by which you might systematically disprove each of the alternatives. What survives, the hypothesis that resists disproof in this Darwinian selection among "multiple working hypotheses:' has a much better chance of being the right answer than if you had simply run with the first idea that caught your fancy. 5. Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it's yours. It's only a way station in the pursuit of knowledge. Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives. See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don't, others will. 6. Quantify. If whatever it is you're explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you'll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses. What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations. Of course there are truths to be sought in the many qualitative issues we are obliged to confront, but finding them is more challenging. 7. If there's a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work (including the premise)-not just most of them. 8. Occam's Razor. This convenient rule-of-thumb urges us when faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well to choose the simpler. 9. Always' ask whether the hypothesis can be, at least in principle, falsified. Propositions that are untestable, un-fulsafiable are not worth much. Consider the grand idea that our Universe and everything in it is just an elementary particle-an electron, say-in a much bigger Cosmos. But if we can never acquire information from outside our Universe, is not the idea incapable of disproof? You must be able to check assertions out Inveterate skeptics must be given the chance to follow your reasoning, to duplicate your experiments and see if they get the same result. 10. The reliance on carefully designed and controlled experiments is key. We will not learn much from mere contemplation. It is tempting to rest content with the first candidate explanation we can think of. One is much better than none. But what happens if we can invent several? How do we decide among them? We don't. We let experiment do it. Acton High School Senior Science Baloney Detection Kit SHERMER'S TEN QUESTIONS FOR BALONEY DETECTION 1 How reliable is the source of the claim? Scientists are usually reliable; pseudoscientists unreliable. As Daniel Kevles showed so effectively in his book The Baltimore Affair, in investigating possible scientific fraud there is a boundary problem in detecting a fraudulent signal within the background noise of mistakes and sloppiness that is a normal part of the scientific process. The investigation of a particular set of research notes in a laboratory affiliated with Nobel laureate David Baltimore (and run by Imanishi Kari) by an independent committee established by Congress to investigate potential fraud, revealed a surprising number of mistakes. But science is messier than most people realize. Errors and sloppiness in raw data happen. The question is: can a distinction be made between intentional and unintentional distortion of the data and interpretations? Baltimore and Kari were exonerated when it became clear that there was no purposeful data manipulation. 2 Does this source often make similar claims? Pseudoscientists have a habit of going well beyond the facts, so when one individual makes numerous such claims it is a sign that they are more than just iconoclasts. Again, this is a matter of quantitative scaling, since some great thinkers often go beyond the data in their creative speculations. Cornell scientist Thomas Gold is notorious for his radical ideas, but he has been right often enough that other scientists listen to what he has to say, and those same scientists are also testing these ideas for their validity. Gold's book, The Deep Hot Biosphere, for example, proposes the heretical idea that oil is not a fossil fuel at all, but the by-product of a massive subterranean colony of bacteria living in rocks. Hardly any earth scientists I have spoken with take this thesis seriously, yet they do not consider Gold a crank. Why? Because he plays by the rules of the game of science. What we are looking for here is a pattern of fringe thinking that consistently ignores or distorts data. . 3 Have the claims been verified by another source? Typically, nonscientists and pseudoscientists will make statements that are unverified, or verified by a source within their own belief circle. We must ask who is checking the claims, and even who is checking the checkers. The biggest problem with the cold fusion debacle, for example, was not that Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischman were wrong; it was that they announced their spectacular discovery before it was verified by other laboratories (at a press conference, no less), and, worse, when cold fusion was not verified anywhere they continued to cling to their belief in the phenomenon despite the lack of evidence. 4 How does this fit with what we know about the world and how it works? An extraordinary claim must be placed into a larger context to see how and where it fits. When pseudoarchaeologists claim that the sphinx was built over 10,000 years ago by an advanced race of humans (because the sphinx shows signs of water weathering that could not have happened after the end of the last ice age), they are not presenting any context for that earlier civilization. Where are the rest of the artifacts of those people? Where are their works of art, their weapons, their clothing, their tools, their trash? This is simply not how history or archaeology works. 5 Has anyone gone out of their way to disprove the claim, or has only confirmatory evidence been sought? This is the confirmation bias, or the tendency to seek confirmatory evidence and reject or ignore disconfirmatory evidence. The confirmation bias is powerful and pervasive and is almost impossible for any of us to avoid It is why the methods of science that emphasize checking and rechecking, verification and replication, and especially attempts to falsify a claim, are so critical. There is so much evidence against cold fusion, for example, that all but a handful of die-hard physicists, chemists, and hopelessly optimistic futurists long ago gave up conducting further research. Yet Acton High School Senior Science Baloney Detection Kit the purveyors of "infinite energy" (there is even a magazine of this title) cling to the slimmest of experimental results and blithely sweep the disconfirming evidence under the rug of conspiracy theories where, for example, oil and electrical conglomerates are said to be preventing the positive evidence from reaching the American public. 6 Does the preponderance of evidence converge to the claimant's conclusion, or a different one? The theory of evolution, for example, is proven through a convergence of evidence from a number of independent lines of inquiry. No one fossil, no one piece of biological or paleontological evidence has "evolution" written on it; instead there is a convergence of evidence from tens of thousands of evidentiary bits that adds up to a story of the evolution of life. Creationists conveniently ignore this convergence, focusing instead on trivial anomalies or currently unexplained phenomena in the history of life. 7 Is the claimant employing the accepted rules of reason and tools of research, or have these been abandoned in favour of others that lead to the desired conclusion? UFOlogists suffer this fallacy in their continued focus on a handful of unexplained atmospheric anomalies and visual misperceptions by uninformed eyewitnesses, while conveniently ignoring the fact that the vast majority (I estimate 90 to 95 percent) of UFO sightings are fully explicable with prosaic answers. 8 Has the claimant provided a different explanation for the observed phenomena, or is it strictly a process of denying the existing explanation? This is a classic debate strategy-criticize your opponent and never affirm what you believe in order to avoid criticism. But this stratagem is unacceptable in science. Proponents of the pyramids as being built by pre-Egyptians offer no evidence of just who these people are, and instead just pick at anomalies in the work of Egyptian archaeologists. Critics of the Big Bang ignore the convergence of evidence of this cosmological model, focus on the few flaws in the accepted model, and have yet to offer a viable cosmological alternative that carriers a preponderance of evidence in favour of it 9 If the claimant has proffered a new explanation, does it account for as many phenomena as the old explanation? The HIV-AIDS skeptics argue that lifestyle (drug use or promiscuity, coupled to a correlation with a naturallyweakened immune system), not HIY, causes AIDS. To make this argument they must ignore the convergence of evidence in support of HIV as the causal vector in AIDS, and simultaneously ignore such blatant evidence as the significant correlation between the rise in AIDS in hemophiliacs just after HIV was inadvertently introduced into the blood supply. On top of this, their alternative theory does not explain nearly as much of the data as the HIV theory. 10 Do the claimants' personal beliefs and biases drive the conclusions, or vice versa? All scientists hold social, political, and ideological beliefs that could potentially slant their interpretations of the data. The question is: how do those biases and beliefs affect the research? It is true that even the most wellintentioned scientists may find themselves searching for facts to fit their preconceptions. But at some point, usually during the peer-review system, such biases and beliefs are rooted out, or the paper or book is rejected for publication. This is why one should not work in a vacuum. Intellect stumbles and falters without critical feedback. If you don't catch your biases in your research, someone else will. Acton High School Senior Science