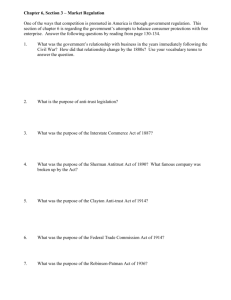

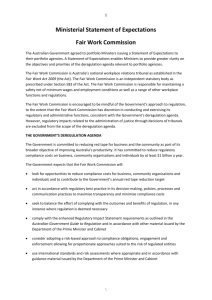

The burden of regulation

advertisement