Female Rebellion in The Bacchae: Criticism and Motivation

advertisement

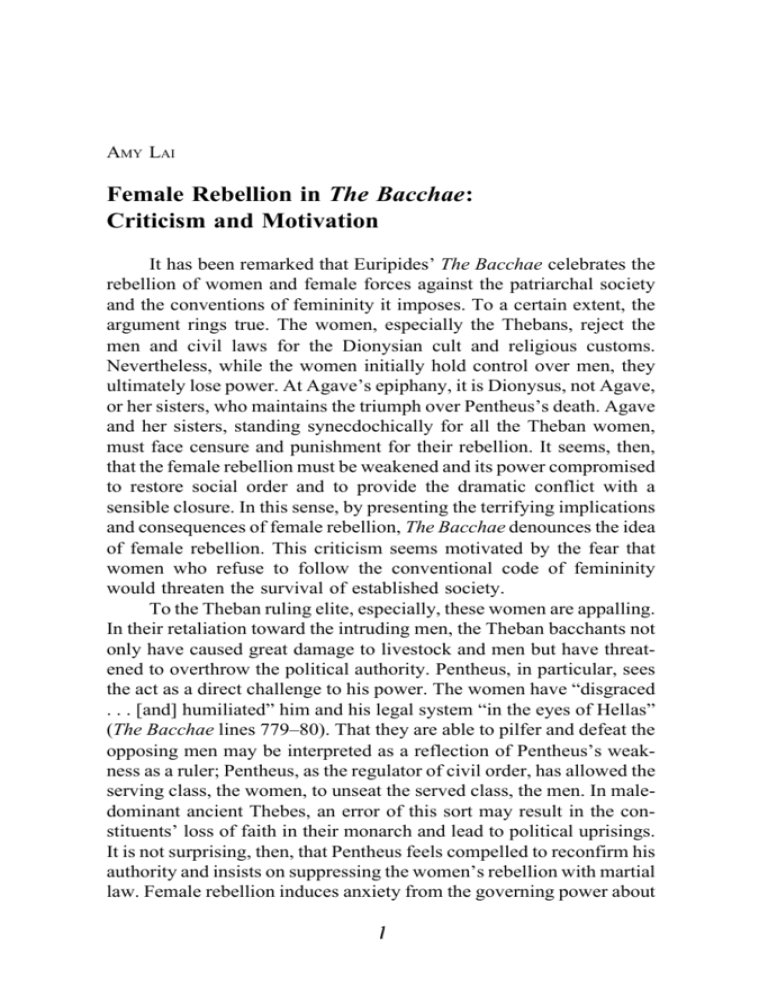

AMY LAI AMY LAI Female Rebellion in The Bacchae: Criticism and Motivation It has been remarked that Euripides’ The Bacchae celebrates the rebellion of women and female forces against the patriarchal society and the conventions of femininity it imposes. To a certain extent, the argument rings true. The women, especially the Thebans, reject the men and civil laws for the Dionysian cult and religious customs. Nevertheless, while the women initially hold control over men, they ultimately lose power. At Agave’s epiphany, it is Dionysus, not Agave, or her sisters, who maintains the triumph over Pentheus’s death. Agave and her sisters, standing synecdochically for all the Theban women, must face censure and punishment for their rebellion. It seems, then, that the female rebellion must be weakened and its power compromised to restore social order and to provide the dramatic conflict with a sensible closure. In this sense, by presenting the terrifying implications and consequences of female rebellion, The Bacchae denounces the idea of female rebellion. This criticism seems motivated by the fear that women who refuse to follow the conventional code of femininity would threaten the survival of established society. To the Theban ruling elite, especially, these women are appalling. In their retaliation toward the intruding men, the Theban bacchants not only have caused great damage to livestock and men but have threatened to overthrow the political authority. Pentheus, in particular, sees the act as a direct challenge to his power. The women have “disgraced . . . [and] humiliated” him and his legal system “in the eyes of Hellas” (The Bacchae lines 779–80). That they are able to pilfer and defeat the opposing men may be interpreted as a reflection of Pentheus’s weakness as a ruler; Pentheus, as the regulator of civil order, has allowed the serving class, the women, to unseat the served class, the men. In maledominant ancient Thebes, an error of this sort may result in the constituents’ loss of faith in their monarch and lead to political uprisings. It is not surprising, then, that Pentheus feels compelled to reconfirm his authority and insists on suppressing the women’s rebellion with martial law. Female rebellion induces anxiety from the governing power about 1 DISCOVERIES the breakup of political order. Therefore, it must be treated as dangerous and looked upon with repugnance in order to allay the fear within its fifth-century male audience. This perception of female rebellion brings up another question— why is female rebellion so dangerous? We have seen how dangerous it can be in overturning the traditional assignment of gender roles, yet we still are not sure why such a change causes so much alarm and aversion. Again, it might be worthwhile to examine Pentheus’s intense reaction to the Theban women’s behavior. Upon his entrance, Pentheus angrily remarks: . . . [R]eports reached me of some strange mischief here, ...................................... I have captured some of [the women]; my jailers have locked them away in the safety of our prison. Those who run at large shall be hunted down out of the mountains like the animals they are— ..................................... In no time at all I shall have them trapped in iron nets and stop this obscene disorder. (The Bacchae 216–32; my emphasis) It seems that Pentheus has correlated order with definite, spatial enclosure and disorder with unbounded area. The reference to boundaries suggests that a hidden system which places people into acceptable and unacceptable categories is at work. The individuals who fit into a prescribed set of socially acceptable patterns are harmless in that they play specific roles within that order. Those who do not are relegated to disorder. The anomalies, accordingly, are dangerous to society for the reason that their indefinable status gives them the potential to disrupt normality (Douglas 37). Thus, the Theban women are dangerous because they have ventured beyond the boundary of civilized metropolis into unexplored nature. In so doing they have acquired a special power not accessible to those who have remained within the confines of society: “to have been in the margins [of society] is to have been in contact with danger, to have been at a source of power” (Douglas 97). That power, as Pentheus fears, allows the women to corrupt society by creating an “obscene disorder” of intoxication and licentiousness. Therefore, to preserve its integrity it becomes necessary for Greek society to urge the suppression of female rebellion. In reality, however, female rebellion grants the women powers far more dangerous than Pentheus has imagined. Through the Dionysiac 2 AMY LAI rituals, the women obtain supernatural energies that allow them to command nature at will. Agave and her Theban sisters, as the messenger reports, can extract wine and honey from trees and rocks simply by tapping their thyrsus. When the women are conscious, their acts appear to be innocuous and peaceful. Nevertheless, at the unconscious level, this power erupts in horrifying destructiveness. In their ecstatic dancing for Dionysus, the women lose rational control over themselves and fall to sociopathic behaviors. They become frenzied hunters who kill animals and humans indiscriminately and devour them raw with savage delight. . . . [Agave] was foaming at the mouth, and her crazed eyes rolling with frenzy. She was mad, stark mad, possessed by Bacchus. . . . ........................... . . . Then Autonoë and the whole horde of Bacchae swarmed upon him. Shouts everywhere, he screaming with what little breath was left, they shrieking in triumph. One tore off an arm, another a foot still warm in its shoe. His ribs were clawed clean of flesh and every hand was smeared with blood as they played ball with scraps of Pentheus’ body. (The Bacchae 1122–37) In this manner, female rebellion arouses fear within established society. The women, in their atavistic violence, have radically inverted the chain of command in the social organization of men and women. No longer are they satisfied with providing milk for their surrogate children, the fawns. The women, once the passive caregivers and the receiver of hunted prey, have abandoned their maternal responsibility and proven their strength as hunters. That they have successfully defeated the men’s weaponry with thyrsi suggests their ability to emasculate—which undoubtedly alarms many men. Perhaps the most frightening aspect of female rebellion lies in its replacement of male companionship with sisterhood. The Chorus attributes the possibility of freedom and joy to the absence of men: she who is “free from fear of the hunt,/ free from the circling beater . . . sprints with the quickness of wind,/ . . . leaping for joy,/ . . . to dance for joy in the forest,/ to dance where the darkness is deepest,/ where no man is” (The Bacchae 869– 79). To permit female rebellion, then, means to accept the existence of the sexes independent of each other. It involves a dramatic reconstruction of social order that would destroy the traditional structure. Hence, by presenting the dangerous outcomes of female rebellion, the play expresses strong disapproval of female rebellion. 3 DISCOVERIES Most importantly, female rebellion dismays society in that it implies pollution. The women, although considered sacred in their religious devotion, have become carriers of pollution. They are “infect[ed]” with a “strange disease,” as Pentheus believes (The Bacchae 353–54). This classification appropriately corresponds to the idea that the powers the women acquire during their departure from society would retain stigmas of their abnormal state if they were to re-enter society. Since these special powers cannot be accommodated within the social structure, they become potentially dangerous pollutants. The women, in turn, become polluted by carrying those powers. Agave and her sisters become impure after bringing a token of their ritualistic hunting (Pentheus’s head) into the city of Thebes. Upon them, Dionysus . . . pronounces this doom: you shall leave this city in expiation of the murder you have done. You are unclean, and it would be a sacrilege that murderers should remain at peace beside the graves [of those whom they have killed]. (The Bacchae 1329; my emphasis, translator’s insertion)1 Dionysus invokes the idea of sacrilege to justify the women’s banishment.2 However, that the women are treated so severely appears to stem from a much stronger source—in particular, the social tendency to “condemn any object or idea likely to confuse or contradict cherished classifications” (Douglas 36). In this sense, [a] polluting person is always in the wrong. He has developed some wrong condition or simply crossed some line which should not have been crossed and this displacement unleashes danger for someone. (Douglas 113) For Theban society, this displacement lies in the murder and consumption of one’s own kin. By hunting Pentheus, Agave and her sisters have breached the most serious taboos. Not only have they slain their kin and smeared themselves with his blood in the wild, but they have returned with it to the city. The blood and the magical energies of nature with which they have contaminated themselves would also symbolically contaminate their family and other Thebans. The women’s action, moreover, would cause both their familial unity and the greater Theban community to disintegrate. Pentheus’s death has resulted in the loss of a family member and a king, and the pollution it brings would not go away unless the entire ruling aristocracy goes into exile, thereby 4 AMY LAI leaving Thebes a headless state.3 The women’s actions, then, signify a multiple pollution. The powerful defilement resulting from female rebellion becomes such a dangerous influence on the public that it must be purged in order for the community to survive. Thus, it seems fitting for dramatic resolution that the Theban women are reduced to their former passivity and exiled. Female rebellion comes with a social impact so frightful that it must be subdued. In The Bacchae, the destructive potency of this rebellion falls under considerable criticism and leads to an attack on female rebellion itself. Yet, the dangerous powers obtained through the rebellion seem to cast it in an aura of mystique that hints at its desirability. This ambivalence is not limited to the women’s liberation. Throughout the play we find ourselves simultaneously repulsed and fascinated by acts of primal violence and by Dionysus’s androgynous traits. Euripides’ clever use of duality arrests our attention and opens up the play to numerous interpretations. Notes 1 The text here is a reconstruction of the lacuna (nearly fifty lines) between lines 1329 and 1380. In the appendix, Arrowsmith points out, albeit conjecturally, that the contents of the lacuna can be rebuilt from the Christus Patiens, “a twelfth-century cento,” and other Euripidean plays. The reconstruction begins after Coryphaeus’ speech with Agave’s mourning over Pentheus’s dismembered corpse. Then, Dionysus appears and announces the fate of those who mock him, Pentheus, and Agave and her sisters. “The manuscript picks up the speed of Dionysus at line 1330 with an account, virtually complete, of the fate of Cadmus” (222). 2 Interestingly, Dionysus condemns the Theban women for practicing the very ritualistic hunting that he endorses and encourages them to do. This paradox seems less mystifying if we examine how the events associated with the female rebellion fit in Dionysus’s agenda. Dionysus initially intends to punish the Theban women for slandering Semele and mocking the circumstances of his birth. By holding them under his spell, he has turned the women, ironically, into his 5 DISCOVERIES devotees and asserted his divine power at the same time. The Theban women’s rebellion, although led by a male god, thus emerges as a potent challenge by the women to their male counterparts and becomes a dominant theme in the play. Nevertheless, as the tension between Pentheus and Dionysus escalates, it begins to lose its thematic importance. Religion, now essentially the struggle between men, takes over female rebellion as the primary issue: Dionysus uses it as a weapon against Pentheus. Therefore, once Dionysus proves the superiority of his divinity over Pentheus’s earthly authority, the women lose power because their rebellion is no longer necessary and they themselves become a threat to Dionysus. It seems convenient for Dionysus to summon the idea of sacrilege to tame his female troops and to end his agenda without involving himself in another battle. In this sense, the problem of female rebellion is less significant in religion than it is in society. That social significance, as we shall see, depends on the concept of pollution. 3 E. R. Dodds also points out that Cadmus has foreseen his fate after he leads Agave to realize what she has done. Addressing Agave, Cadmus says ominously that he “must go, a banished and dishonored man” (Euripides line 1313). The “Greek way of thinking” connects with the idea that “a pollution so abominable could hardly be expiated save by the expulsion of the whole guilty family” (Dodds 234). ❦ Works Cited Dodds, E. R. Commentary. Bacchae. Euripides. Ed. E. R. Dodds. Oxford UP, 1960. Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1966. Euripides. The Bacchae. Trans. William Arrowsmith. Euripides V: Electra, The Phoenician Women, The Bacchae. The Complete Greek Tragedies. Ed. David Grene and Richard Lattimore. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1959. 6