Unravelling the US Dollar Puzzle

advertisement

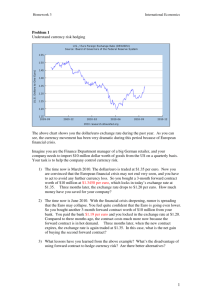

Economics 3rd July 2003 AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH Unravelling the US Dollar Puzzle What Drives the US Dollar? The US dollar strengthened significantly by around 17½% from early 2000 to mid 2002. The underlying strength of the US economy and the attractiveness of returns in the 1 Chart 1: US TWI and Euro (Inverse) Jeff Oughton Senior Economist +(613) 8641 3469 Jeff_Oughton@national.com.au 0.80 110 105 US TWI (LHS) EURO(RHS) 0.90 100 1.00 95 Cents 1.10 90 1.20 85 1.30 80 1.40 75 70 1.50 Q2 87 Q2 88 Q2 89 Q2 90 Q2 91 Q2 92 Q2 93 Q2 94 Q2 95 Q2 96 Q2 97 Q2 98 Q2 99 Q2 00 Q2 01 Q2 02 The US TWI has subsequently fallen by around 13½% from its mid 2002 peak, while the Euro/$US has appreciated by around 24% over this period. The recent decline of the US dollar has been attributed to various factors including, the sustainability of the size of the US current account by increasing the risk premium, the patchy economic performance and narrowing interest rate differentials. While these explanations are all intuitively appealing, there is little empirical evidence of their causal relationship. 2 Major Currency TWI. Alan Oster Chief Economist +(613) 8641 3464 Alan_Oster@national.com.au US (especially during the technology boom) have been claimed as the main justifications for US dollar strength over this period. On the other hand, the slower pace of growth in the Euro area and structural labour and product market rigidities were said to be the main cause of the Euro’s weakness. The movement in the US dollar over this period was reflected in many global currency crosses, especially the Euro. Japan’s declining trend economic growth since the late 1980s suggests that it has not been a viable option for investors, hence the flow of capital has been largely between the Euro area and the US. Indeed 2 the inverse of the synthetic Euro has been the mirror image of the US TWI (see chart below). Index Points 1 Since mid 2002 the US dollar TWI has depreciated by around 13½%, resulting in significant movements in international currency crosses, and for that matter, interest rates. A critical question presently for global currencies (including the $A) and global interest rate settings is whether US dollar weakness will persist. Many analysts have recently revised their exchange rate and interest rate forecasts, assuming a weaker US dollar will continue in the medium-term, mainly on the basis that a correction in the US dollar is long overdue given fundamentals, especially a high current account deficit to GDP ratio. On the other hand, some believe that the weakness in the US dollar is short-lived, and expect a bounce in the currency once signs of an economic recovery in the US emerges. Some strengthening in the US dollar in recent weeks, may be supportive of that scenario. While many views of the US dollar abound, there is little statistical evidence supporting the arguments. This research paper takes a close look at the US dollar and finds a stable relationship between the US dollar TWI and the trend productivity ratio between the US and the Euro area since mid 1987. Granted this relationship continues to hold in the foreseeable future, our model sees the US TWI weaken moderately further. Current economic growth forecasts for the US and Europe are consistent with further moderation in the trend productivity ratio, resulting in an easing in the US dollar (TWI) to around 89 cents and the Euro/$US strengthening slightly to around 1.18 by the end of 2005. The direction of the US dollar has important implications globally and locally. For instance, if our forecasts are right, in the US it may alleviate any deflationary pressures and the need for further rate cuts. Domestically a weaker US dollar increases the prospect of the $A/$US making further gains to the low 70s in 2004 and staying around 65-67 US cents in 2005. A stronger local currency will result in tighter monetary conditions, allowing the cash rate to move slightly lower in the near-term or delay the need for rate increases. Before 1999, the Euro is proxied by the Deutschmark. Jennifer Babet Economist +(613) 8641 3762 Jennifer_M_Babet@national.com.au National Australia Bank Economics 3rd July 2003 AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH This paper attempts to model the US TWI. As forecasting of equity returns is difficult, the focus is placed on fundamental economic drivers. Fundamental models are useful for long-term forecasting i.e. not for daily or weekly forecasts. As a starting point, trend GDP growth differentials between the US and Europe were used as a proxy for relative returns but did not yield any significant results. On the other hand, a surprisingly robust relationship was found between the US TWI (and the Euro/$US) and the trend productivity ratio between the US and the Euro area since mid 1987 (see below). On the other hand, this variable cannot explain the mid 1980’s spike in the US dollar. The trend productivity ratio has a better fit with the US TWI rather than the Euro/$US. This relationship may have developed since 1987 due to Japan’s economic problems. Consequently, it is possible that the link may weaken once Japan’s economic malaise is overcome – not a medium-term prospect. Chart 2: US TWI and Trend Productivity Ratio US TWI Chart 3: US Productivity 7.00 Productivity - Output per Hour GDP/Employment 5.00 3.00 1.00 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 Q1 -1.00 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 -3.00 7.00 US productivity growth has consistently outpaced European productivity growth since the late 1990s. This has been attributed mainly to more high tech industries and a higher take-up of technologies in the US. That said, European productivity growth has been adversely impacted by increased employment growth in low productivity areas. While US productivity continues to significantly exceed the Euro area (see chart below), the ratio peaked in early 2002 and has subsequently narrowed. 6.00 Chart 4: Trend Productivity Growth 3 120 To ensure consistency in the productivity measures, GDP divided by employment was used. The official productivity growth for the US has been higher in recent years than GDP/employment (see chart below), however, the latter appears to have more explanatory power for the US TWI or Euro/$US. Annual % change We use a Major Currency measure of the US TWI in the paper. This gives weight largely to the Canadian dollar (30.3%), Euro (28.7%), Japanese Yen (25.6%) and UK pound (8.0%). This measure attempts to capture financial pressures on the US dollar, as well as the competitiveness of US goods relative to major economies. Undoubtedly capital flows rather than trade flows have been a major driver of currencies in recent years. According to the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) 2001, the Euro/$US accounts for around 30% of global foreign exchange turnover, the Yen/$US 20% and the Pound/$US 11%. Productivity 110 5.00 3 100 3.00 2.5 Ratio Index Points 4.00 2.00 2 90 80 0.00 Ratio 1.00 1.5 -1.00 1 70 -2.00 Q2 87 Q2 88 Q2 89 Q2 90 Q2 91 Q2 92 Q2 93 Q2 94 Q2 95 Q2 96 Q2 97 Q2 98 Q2 99 Q2 00 Q2 01 Q2 02 0.5 EURO AREA US 0 3 Trend based on Hodrick Prescott filter smoothing factor 1600. Unravelling the US Dollar Puzzle Q2 84 Q2 85 Q2 86 Q2 87 Q2 88 Q2 89 Q2 90 Q2 91 Q2 92 Q2 93 Q2 94 Q2 95 Q2 96 Q2 97 Q2 98 National Australia Bank Q2 99 Q2 00 Q2 01 Q2 02 2 Economics 3rd July 2003 AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH The productivity relationship also accords well with assetmarket/portfolio-based theories as productivity is closely linked to future returns/profits, income and economic growth. For instance, the late nineties was a virtuous economic circle in the US, with increased productivity associated with the technology boom resulting in expectations of higher profits and incomes, the surge in the NASDAQ, increased wealth effects on consumption, increased capital inflow (higher current account deficit), strong business investment and higher overall economic growth. In contrast, the reduction in the trend productivity differential, points to lower relative future profits/equity returns, reduced wealth effects on consumption and investment, lower economic growth and reduced capital inflow. US Dollar To Weaken Moderately Further Chart 2 showed a close relationship between the US TWI and the trend productivity ratio. Nevertheless, there was no evidence of cointegration using the Johansen Maximum Likelihood methodology. On the other hand, the error correction term is quite large and highly significant suggesting otherwise. Nontheless, the US TWI has been modelled using a Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) framework over the period 1987:2 to 2002:4. This method includes both the long-run relationship between the variables, and the dynamic adjustment. The coefficient on the trend productivity ratio in the long-run equation is 6.4, suggesting that a 1% increase in the relative productivity ratio results in an appreciation in the US TWI by 6.4 index points. The error-correction term is -0.37, indicating fairly rapid adjustment to the long-run. The fit of the equation (both long-run and short-run) against the actual US TWI 4 We have modelled the nominal exchange rate rather than the real exchange rate. Nominal and real exchange rates have been highly correlated in recent years. Unravelling the US Dollar Puzzle are shown in the chart below. A forecast of the US TWI until the end of 2005 is also shown on the chart. Chart 5: Forecast US TWI 120 110 (F) Index Points 100 90 80 70 longrun actual shortrun 60 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 Assuming economic growth in the US averages around 2½% in 2003, 3¾% in 2004 and 3¼% in 2005, while the Euro area records economic growth of around 1% in 5 2003, 1¾% in 2004 and 2% in 2005 are consistent with weaker trend growth in productivity in the US and strengthening trend productivity growth in Europe over the next two years (see chart below). This sees the trend productivity (GDP/employment) ratio continuing to narrow, resulting in the US TWI easing moderately further to around 89 Index points by the end of 2005. Chart 6: Forecast Trend Productivity 3 2.5 2 Annual % change How does the relationship between productivity and the exchange rate reconcile with economic theory? Some economic theory suggests that increased productivity results in lower prices, a deterioration in the terms of trade, resulting in a depreciation in the currency (real 4 exchange rate ). On the other hand, the BalassaSamuelson theory makes the distinction between the price of traded and non-traded goods and predicts that if the productivity of traded goods relative to non-traded goods is growing faster in the home country relative to abroad, then there should be a real appreciation of the home country’s real exchange rate. 1.5 1 Euro Area US 0.5 0 Q2 87 5 Q2 88 Q2 89 Q2 90 Q2 91 Q2 92 Q2 93 Q2 94 Q2 95 Q2 96 Q2 97 Q2 98 Q2 99 Q2 00 Q2 01 Q2 02 Q2 03 Q2 04 Q2 05 These are close to the latest Consensus Forecasts. National Australia Bank 3 Economics 3rd July 2003 AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH Of course, these forecasts are highly sensitive to the growth assumptions used, which will also depend on the currency. The results suggest that US economic growth will need to significantly outpace the Euro area to result in the US TWI strengthening markedly. Similarly, the results suggest that provided US productivity growth continues at a reasonably strong pace, an abrupt adjustment to the US dollar should be avoided. While productivity growth is expected to remain strong in the US, the consensus is that technological innovation and its take-up is unlikely to be sustained at the rates observed in the late 1990s. That, together with the shock from the bursting of the equity market bubble, point to some further easing in relative trend productivity. On the other hand, after falling significantly since mid 1995, trend productivity in Europe has turned and assuming the above growth projections, will strengthen further. What About the $A/$US? The $A/$US has also been closely linked to the US dollar TWI, however, only since March 2000 (see chart below). the $A/$US is now inside the standard error bands of the old long-run model (see chart below). The long-run model points to the $A/$US strengthening to around 71 cents by early 2004 and moderating slightly to around 65 US cents by the end of 2004, as the Australian/US interest rate differential narrows. Underlying this projection is a moderate global economic recovery (CRB increases modestly), the cash rate ranging from 4¼% in September 2004 to 5% by the end of 2004 in Australia and the Federal Funds rate rising progressively to 2¼% by the end of 2004 from 1% currently in the US. Chart 8: Fundamental $A/$US Model $A/$US 1 standard error band +/- 4 cents 0.9 (f) 0.8 0.7 Chart 7: US TWI and $A/$US 0.6 50 1 0.5 60 0.9 Actual AUD 0.4Feb-84 Dec-85 Oct-87 Aug-89 Jun-91 Apr-93 Feb-95 Dec-96 Oct-98 Aug-00 Jun-02 Apr-04 70 Jan-85 Nov-86 Sep-88 Jul-90 May-92 Mar-94 Jan-96 Nov-97 Sep-99 Jul-01 May-03 80 0.7 90 Index Points US cents 0.8 0.6 100 0.5 AUD (LHS) US TWI INVERSE (RHS) 0.4 110 120 Dec-83 Jun-85 Dec-86 Jun-88 Dec-89 Jun-91 Dec-92 Jun-94 Dec-95 Jun-97 Dec-98 Jun-00 Dec-01 Jun-03 Prior to March 2000, the $A/$US had a stable relationship with the CRB, interest rate differentials and/or relative equity returns. However, from early 2000 until more recently, a long-run equation using those variables performed poorly, with the actual currency falling well outside the standard error bands of the long-run equation – close to 20 cents below the long-run model forecast in early 2001. At the time, it was difficult to gauge whether this break was permanent or transient. However, it is now evident that the break was due to US dollar strength. As the spike in the US TWI has now almost fully unwound, Unravelling the US Dollar Puzzle Implications for Monetary Policy In the US, the Federal Reserve recently cut the Federal Funds rate by a further 25 bps to 1%, mainly on concerns of deflation. A reduction in price pressures in the US largely reflects excess capacity following the bursting of the equity market bubble and also continued solid growth in productivity. Although the US is a closed economy, a weaker currency will bode well for the expected US economic recovery, assist to reduce deflationary pressures and potentially the need for further rate cuts. The ECB cut its Repo rate by 50 bps in early June, mainly due to ongoing patchy economic data, the realignment of the Euro and the benign inflation outlook. The appreciation of the Euro is hurting German manufacturers. Given prospects of the Euro/$US strengthening mildly to around 1.18 US dollar, and little flexibility for fiscal policy (due to the Stability and Growth pact) the ECB may ease a further 50 bps in coming months. National Australia Bank 4 AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH Economics 3rd July 2003 In Australia, further appreciation in the $A/$US will result in a some tightening in monetary conditions. Whether the RBA should respond to movements in the exchange rate depends on whether the change in the currency is transitory or longer-term. As shown in this paper, the adjustment in the US dollar appears to be longer-term, raising prospects that the strengthening in the $A/$US may persist. With domestic demand set to slow over the next year and the global economic recovery expected to be modest, the higher $A/$US allows the RBA to ease monetary policy moderately in coming months or delay for longer any upward adjustments. Jennifer_M_Babet@national.com.au Unravelling the US Dollar Puzzle National Australia Bank 5 Economics 3rd July 2003 DISCLAIMER: So far as the law allows, National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937 (“the National”) does not warrant or represent that this document (or the information set out or referred to in this document) is accurate, reliable, complete or contemporary. National expressly advises that, to the extent permitted by the law of Victoria, Australia, by which law use and all other matters relating to this document are governed, it disclaims all and any responsibility for and shall not be liable in any way whatsoever (whether in negligence or otherwise) for any loss or damage which may be suffered by any person relying upon this document (or the information or conclusions contained in this document). This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. The National, its affiliates, and employees may hold a position or act as price maker in the financial instruments of any issuer discussed within this document or act as underwriter, placement agent, adviser or lender to such issuer. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and recipients should not rely upon the contents of this document but should make their own assessment and evaluation. © Copyright National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937. U.S DISCLAIMER: This information has been prepared by National Australia Bank or one of its affiliates or subsidiaries (collectively, “NAB”). If it is distributed in the United States, such distribution is by National Australia Capital Markets, LLC (NACM) which accepts responsibility for its contents. Any U.S. person receiving this information wishes further information or desires to effect transactions in the securities described herein should call or write to NACM, 200 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10166 (or call (877) 377-5480). The information contained herein has been obtained from, and any opinions herein are based upon sources believed to be reliable and no guarantees, representations or warranties are made as to its accuracy, completeness or suitability for any purpose. Any opinions or estimates expressed in this information is our current opinion as of the date of this report and is subject to change without notice. The principals of NACM or NAB and/or its affiliates may have a long or short position or may transact in the securities referred to herein or hold or transact derivative instruments, including options, warrants or rights with securities, or may act as a market maker in the securities discussed herein and may sell such securities to or buy from customers on a principal basis. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of the securities described herein or for any other action. It is intended for the information of clients only and is not for publication in the press or elsewhere. 6