DRUID Working Paper No 02-11 Authority and Discretion : Tensions

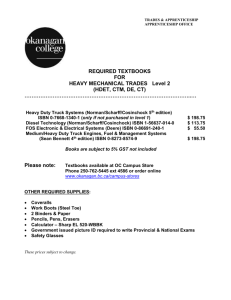

advertisement