Counterproductive work behavior in relation to personality type and

advertisement

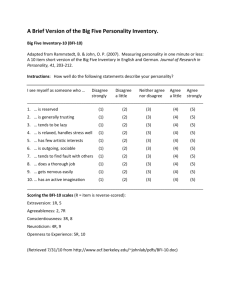

Available Online at http://iassr.org/journal 2014 (c) EJRE published by International Association of Social Science Research - IASSR ISSN: 2147-6284 European Journal of Research on Education, 2014, 2(Special Issue 6), 212-217 European Journal of Research on Education Counterproductive work behavior in relation to personality type and cognitive distortion level in academics Metin Piskin a *, Muge Ersoy-Kart b, İlkay Savci c , Ozgur Guldu d b a First affiliation, Address, City and Postcode, Country Second affiliation, Address, City and Postcode, Country c Third affiliation, Address, City and Postcode, Country d Third affiliation, Address, City and Postcode, Country Abstract Click here and insert abstract your text. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. Insert an abstract of between 200-250 words, giving a brief account of the most relevant aspects of the paper. © 2013 European Journal of Research on Education by IASSR. Keywords: First keywords, second keywords, third keywords, forth keywords; 1. Introduction Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) is defined as “voluntary behavior that violates significant organizational norms and in so doing threatens the well-being of an organization, its members, or both” (Robinson and Bennett, 1995). According to Henle (2005), these “intentional” behaviors can be directed toward organizations (e.g., theft, sabotage) and also toward individuals in the workplace (e.g., making fun of others, playing mean pranks). Some theorists (e.g., Berkowitz, 1998) have linked these “bad” employee behaviors to negative emotions such as anger and/or frustration. Spector et al. (2006) developed a classification of CWBs that categorizes these deviant behaviors into five dimensions: abuse—harmful and nasty behaviors that affect other people; production deviance—purposely doing one’s job incorrectly or allowing errors to occur; sabotage—destroying organizational property; theft—wrongfully taking the personal goods or property of another; and withdrawal—avoiding work through being late or absent. This model of CWBs can be seen in Table 1. These behaviors are likely to be influenced by individuals’ personality traits for the reason that individuals make conscious choices about whether to engage in these behaviors (Mount et al., 2006). Big Five taxonomy is known the most widely accepted method of assessing personality (Mount et al., 2006). Specifically, extraversion refers to a pronounced engagement with the external world; agreeableness reflects the degree of one’s sense of cooperation and * E-mail address: author@institute.xxx Title of the study social harmony; conscientiousness concerns the way in which we control, regulate, and direct our impulses; neuroticism refers to one’s tendency to experience negative feelings; and openness to experience describes imaginable and creative individuals (Johnson and Ostendorf, 1993). A meta-analysis by Berry et al. (2007) indicated that agreeableness and conscientiousness were the strongest predictors of a CWB composite score. Specifically, agreeableness was predictive of interpersonally directed CWBs, while conscientiousness was predictive of organizationally directed CWBs. Hogan (2004) stated that personality traits ‘do matter at work’. Table 1 - The Model of Counterproductive Work Behaviors (Robinson and Bennett, 1995) Organizational Interpersonal severe Property deviance (A) serious organization directed offences Personal aggression (B) serious interpersonally directed offences minor Production deviance (C) minor organizationally directed offences Political deviance (D) interpersonally directed but minor offences Another variable that can contribute to exhibition of CWBs is cognitive distortions (CDs). As Fair (1986) defined, these are systematic logic errors in the individual’s mind. Researchers suggest that CDs can also be observed in normal individuals, but depressive individuals perceive stressful situations more negatively and exaggeratedly than the normal ones (Leahey, 2007). According to Murad (2002), CDs are strongly related to aggressive behavior. It is observed that individuals who take refuge behind CDs have a more external locus of control and lower self-respect, internalize loneliness, are weaker in coping with stress, and are more prone to depression and anxiety. They can be described as possessing a tendency to blame themselves for negative unwanted events that have occurred in their lives, (i.e., self-blame), feeling unable to control important aspects of their lives (i.e., helplessness), lacking perseverance in tasks requiring an expectation of a positive future outcome (i.e., hopelessness), and expressing a tendency to view the world as a dangerous place (i.e., preoccupation with danger) (Brown et al., 2009). The aim of the present study was to determine whether type of CWBs was influenced by personality traits and CD levels of individuals. Our sample was chosen from career academics. The proposed model is presented below. The research questions derived from this model are as follows: 1. Do CWB levels of the participants differ significantly with regard to demographic variables (age, sex, education level, term of employment)? 2. Are there any significant differences between personality types groups (high-low) with regard to CWB exhibited? 3. Are there any significant differences among CD levels of the participants in terms of exhibited levels of the CWB subscales? 4. Can CWB exhibited be predicted by personality types and CD? 5. Are there any significant correlations between CWB types, personality, and CD dimensions? 213 Authors’ Name 2. Method 2.1. Respondents The sample consisted of 71 academics: 38 women (53.5%) and 33 men (46.5%). In terms of age, 73.2% of the respondents were under 35 years old, while 26.8% of them were 35 years old or older. About 96% of the participants had a master’s degree, whereas only 4% of them were studying for their PhDs. The frequencies and percentages of the demographics of the participants are summarized in Table 2. Table 2 - The distribution of the sample by sex, age, educational level, and term of employment Sex Age Educational level Term of employment Female Male Under 35 years 35 years old or older Master’s degree PhD students Less than 1 year 1–5 years 5–10 years 10–15 years 15–20 years More than 20 years Frequencies 38 33 52 19 68 Percentages 53.5 46.5 73,2 26,8 96.0 3 9 21 11 18 5 3 4.0 12.7 29.6 15.5 25.4 7.0 4.2 2.2. Measures The Counterproductive Work Behavior Checklist (CWB-C), CD Scale (CDS) (Briere, 2000), and the Big Five Personality Scale (BFPS) (Benet-Martinez and John, 1998) were used to obtain answers to the research questions. Additionally, a demographic information form was completed by the respondents. CWB-C. The main instrument used for the study was the 32-item Turkish adaptation of the English version of the CWB-C (Öcel, 1993), originally developed by Spector et al. (2006). The scale measures five components of CWB: abuse toward others, production deviance, sabotage, theft, and withdrawal but from these only four were used in the Turkish version (abuse toward others, theft, withdrawal, and sabotage). Öcel (2010) found that the Turkish version of the scale is valid and reliable. Cognitive Distortion Scale: The 40-item CD Scale (Briere, 2000) assesses five factors: self-criticism, self-blame, helplessness, hopelessness, and preoccupation with danger. Ağır (2007) reported a high internal consistency of the scale for a Turkish sample (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .88 to .91). Big Five Personality Scale: Personality was measured with the 44-item Big Five Personality Inventory (BenetMartinez and John, 1998), which assesses five main personality traits: agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the scale were assessed by Sümer (2005). He found that the Turkish version of the scale is valid and reliable (Çetin, 2008). 214 Title of the study 3. Results The aim of the present study was to investigate whether CWB type was influenced by personality traits and CD levels of the respondents. In all analyses of variance, personality type and distortion style were chosen as independent variables. An alpha value of 0.05 was used throughout. The analyses were conducted with SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). 3.1. Analysis of Comparisons between Groups According to the personality types, there were significant differences with regard to abuse (F (1, 56) = 4.48, p<.05) and sabotage behaviors (F (1, 56) = 5.79, p<.05) in terms of agreeableness scores. The group classified as high in agreeableness (Group 1) had a mean score of 16.75, whereas the group classified as low in agreeableness (Group 2) had a mean score of 19.84 for the abuse scale. Furthermore, the group classified as high in agreeableness (Group 1) had a mean score of 3.27 and the one classified as low in agreeableness (Group 2) had a mean score of 2.79 for the sabotage scale. These results indicate that while agreeableness levels of the participants increase, the levels of the sabotage and abuse behaviors decrease. With respect to withdrawal score, there was a significant difference between the groups in terms of the main effect of conscientiousness level (F (1, 56) = 4.18, p<.05). The results showed that in the conscientiousness scale, the mean score of Group 1 was 7.67, while that of Group 2 was 9.18, which indicated that the more conscientiousness the employee was, the lower his or her withdrawal behaviors were. With respect to withdrawal score, there was also a significant difference between the groups in terms of the interaction effect of openness to experience and helplessness (F (1, 56) = 5.15, p<.05). The group means that constituted this difference are 6.43 for Group 1 (high helplessness and high openness) and 10.31 for Group 2 (high helplessness and low openness). The results revealed that the group that has high helplessness and high openness levels exhibits significantly less withdrawal behaviors than Group 2 does. In terms of sabotage behaviors, there was a significant difference between the groups in terms of the interaction effect of neuroticism and hopelessness (F (1, 56) = 4.30, p<.05). The group means that constituted this difference are 3.35 for Group 1 (low hopelessness and high neuroticism) and 2.15 for Group 2 (high hopelessness and low neuroticism). The results show that the group that has a high level of neuroticism but a low level of hopelessness engages in sabotage behaviors significantly less than Group 2 does. 3.2. Regression Analysis of CWB Types It has been theorized that personality and CD scores are useful in predicting the academics’ CWB levels. The regression equations for CWBs dimensions are shown below: Abuse = 16.79 – 0.26 neuroticism + 0.16 extroversion + 0.54 self-criticism [Multiple correlation between these variables and abuse is 0.68, and this is a significant value (F [10,60] =11.86, p > .05). In other words, these variables were responsible for explaining 46% of the total variance]. Sabotage = 3.50 + 0.17 self-criticism [Multiple correlation between sabotage and self-criticism is 0.58, and this is a significant value (F [10,60] =7.04, p > .05). In other words, this variable was responsible for explaining 34% of the total variance]. Theft = 7.19 – 0.17 neuroticism + 0.25 self-criticism [Multiple correlation between theft and these variables are 0.61, and this is a significant value (F [10,60] =8.42, p > .05). In other words, neuroticism and self-criticism were responsible for explaining 38% of the total variance]. Withdrawal = 6.10 + 0.12 extroversion + 0.27 self-criticism [Multiple correlation between withdrawal and these variables are 0.49, and this is a significant value (F [10,60] =4.38, p > .05). In other words, extroversion and selfcriticism variables were responsible for explaining 38% of the total variance]. 215 Authors’ Name 3.3. Results of Correlation Analysis The correlation coefficients among personality types, CD styles, and CWB dimensions are shown in Table 3. Table 3 - Correlation Coefficients among Personality-CD and CWB-Types Neuroticism Extroversion Openness to Experience Agreeableness Conscientiousness Helplessness Hopelessness Preoccupation with danger Self-criticism Self-blame Age Abuse Theft Withdrawal Sabotage .00 -.01 -.11 -.26* -.19* .49* .49* .49* .62* .49* .06 -.06 -.06 -.10 -.21* -.15 .43* .44* .42* .56* .93* .02 .05 .05 -.07 -.17* -.20* .33* .34* .33* .43* .75* -.06 .02 -.02 -.12 -.25* -.18* .36* .39* .40* .53* .87* .14 p< .05 As can be seen from Table 3, agreeableness is correlated negatively with all CWB types. These results indicate that those who scored high in the agreeableness dimension engage in CWBs more seldom. Similarly, the more conscientiousness the academics are, the less CWBs (except theft) they are expected to exhibit. However, the results of correlation analysis signify that when participants’ CD scores rise, their engagement in CWB grows. In contrast, the age of respondents is not correlated significantly with their CWB scores. 4. Discussion CWB is a new research area in Turkey. CWB sometimes can be seen as an innocent reaction to unfair treatment by employers. As is known, labor unions are becoming steadily weaker in every country, including Turkey. Therefore, workers have been left petrified and powerless in the labor market. The only weapon they can use to stand up for their rights is engaging in CWBs, especially the passive type. As well as employers, organizational conditions can cause CWBs too. Instrumental deviance can be seen therefore as a means to overcome these two “hostiles”. Aggression can also be a result of these feelings. Actually, fairness perceptions in work settings relate to retaliatory behaviors against the organization (Skarlicki & Folger, 1997), but sometimes individuals engage in CDs when they perceive and interpret real-life situations. Moreover, personality differences can play an important role in the display of deviant behaviors at work. Our findings show that two personality traits (openness to experience and neuroticism) and two dimensions (hopelessness and helplessness) of CD together reveal two dimensions (withdrawal and sabotage) of CWBs. In other words, while the scores of openness to experience decrease, at the same time helplessness of the participants increases and withdrawal increases too. While hopelessness and neuroticism scores are increasing together, sabotage behaviors (CWB) are also increasing. According to the results from regression analysis, self-criticism predicts all dimensions of CWBs positively and neuroticism predicts abuse and theft behaviors negatively. According to the results of correlation analysis, the most remarkable findings are as follows: there are significant negative correlations between CWBs and agreeableness, and also between CWBs and conscientiousness. Briefly, there are significant positive correlations between all dimensions of CD and CWBs. No doubt these findings are important to explain personal traits and perceptions as factors to influence the workplace environment negatively. In the research the structural circumstances of the workplace were ignored as variables. This limitation should be kept in mind. However, it is clear that structural factors have important effects 216 Title of the study on the lives of individuals. Personality and CD are influenced by previous life experiences of the individual. Therefore, structural factors work as latent variables in our model. Moreover, it must be added that CWB terminology was created after the 1980’s. It should be kept in mind that new organizational management models have been developed such as HRM and TQM in which an individual is on his/her own when seeking his/her rights in opposition to management policies. Individualistic HR approaches such as performance evaluation, determination of salaries individually, seeking appropriate career opportunities, and lack of collective negotiating tools (for example unions) create deviant workplace behaviors. To sum up, while psychology is uncovering the realities of workplace behaviors, care must be taken to ensure that it is not used as an instrument to enable capitalist management applications. We can give an example from this research; according to our results, a manager can make the decision not to give job opportunities to people who do not have suitable personality traits and CD in order to prevent CWBs in the workplace! References Ağır, M. (2007). Üniversite Öğrencilerin Bilişsel Çarpıtma Düzeyi ile Problem Çözme Becerileri ve Umutszuluk Düzeyleri Arasındaki İlişki. Ankara: Yayınlanmamış Doktora Tezi. Berry, C. M., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 410–424. Brown,C., Trangsrud, H.B., & Linnemeyer, R.M. (2009). Battered Women’s Process of Leaving. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(4), 439-456. Çetin, F. (2008). Kişilerarası İlişkilerde Kendilik Algısı, Kontrol Odağı ve Kişilik Yapısının Çatışma Çözme Yaklaşımları Üzerine Etkileri: Uygulamalı Bir Araştırma. Ankara: Yayınlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi. Henle, C. (2005). Predicting workplace deviance from the interaction between organizational justice and personality. Journal of Managerial Issues, 17, 247–264. Hogan, R. (2004). Personality psychology for organizational researchers. In B. Schneider & D. B. Smith (Eds.), Personality and Organizations (pp. 3–21). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Johnson, J.A., & Ostendorb. F. (1993). Clarification of the Five Factor Model with the Abridged Big Five-Dimensional Circumplex. Journal of Personality and Social Psvchology, 65, 563-576. Leahy, R.L. (2007). Bilişsel Terapi ve Uygulamaları–Tedavi Müdahaleleri İçin Bir Kılavuz. İstanbul: Litera Yayıncılık. Mount, M., Ilies, R., & Johnson, E. (2006). Relationship of personality traits and counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effects of job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 59, 591–622. Murad, H. A.I (2002). Cognitive Processes and Aggression in Middle School Children. U.S.A. Öcel, H. (2010). Üretim Karşıtı İş Davranışları Ölçeği: Geçerlilik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları. 13 (26), 18-26. Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A Typology of Deviant Workplace Behaviors: A Multidimensional Scaling Study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 555–572. Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997). Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82,434-443. Spector, P. E., & Fox, S. (2005). The stressor-emotion model of counterproductive work behavior. In S. Fox & P. E. Spector (Eds.), Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets (pp. 151–174). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Spector, P. E., Fox S., Penney L. M., Bruursema K., Goh A., & Kessler S., (2006). The Dimensionality of Counterproductivity: Are All Counterproductive Behaviors Created Equal? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 446-460. 217