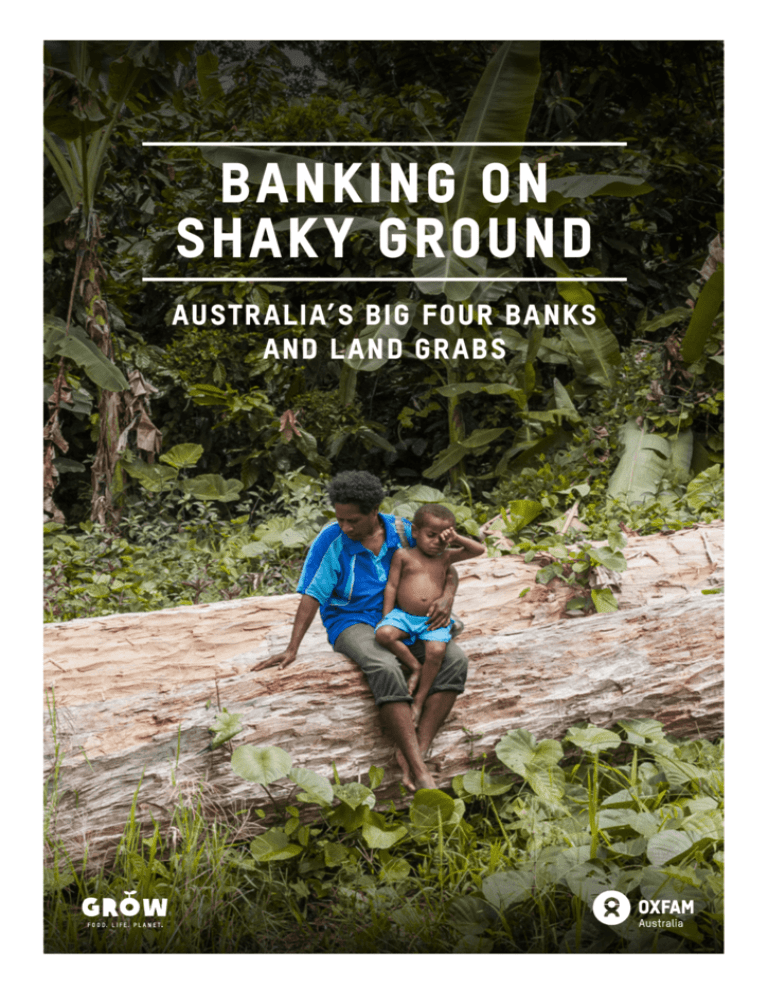

Banking on Shaky Ground

advertisement