Tim Severin In Search of Robinson Crusoe Summary

advertisement

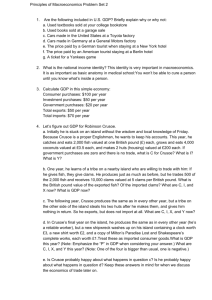

Tim Severin In Search of Robinson Crusoe Summary Tim Severin scrutinizes the famous adventure novel Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe in order to separate myth from reality and to establish the identities of the possible prototypes for Defoe’s immortal character. He also describes his travels to the locations in the South Pacific and the Caribbean Sea where seventeenth and eighteenth-­‐century English seafarers were stranded. In Chapter 1, “Maroon,” Severin reviews the existing accounts of the story of Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk who was picked up by the English privateer ship, The Duke, on the South Pacific island Juan Fernandez, about 400 miles off the Chilean coast, in 1707. Upon the ship’s return to England in 1711, Selkirk’s story became well known though the publications of the voyage’s account by several members of the crew, namely the books by Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea, Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, and William Dampier, New Voyage Round the World. Selkirk's story was also popularized by essayist Richard Steele who claimed that he had interviewed Selkirk. It has been argued that Selkirk was the prototype for Robinson Crusoe. However, Severin points out various discrepancies between Selkirk's story and Defoe's novel including the fact that Defoe places Crusoe on the island in the Caribbean off the Orinoco mouth, not in the South Pacific. In Chapter 2, “Isla Robinson Crusoe,” Severin travels to Isla Robinson Crusoe (formerly known as Juan Fernandez.) He surveys the island and compares its geography, flora and fauna to the island described in Defoe’s novel. He also compares Robinson’s experiences, as narrated by Defoe, to the harsh realities of living on Juan Fernandez based on the memoirs written by Captain George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World. Shelvocke and his crew of 70 men survived the shipwreck and stayed on the island for three years and seven months. Out of 106 men who left England in 1718, only 33 returned home in 1722. Severin’s conclusions cast a shadow of doubt over this widely accepted theory that Selkirk was the prototype for Crusoe. In Chapter 3, “Moskito Man,” Severin explores the origins of another important character in Defoe’s novel, Man Friday. Using the account of English pirate William Dampier (1697), Severin describes the story of Will the Miskito who lived alone on Juan Fernandez for over three years. Severin travels to the Miskito Coast on the Caribbean side of Honduras and Nicaragua to observes the way of life of Miskito people, paying a special attention to their methods of hunting, fishing and their survival skills in general. This chapter also contains the story of Captain Nathaniel Uring and his men who shipwrecked near Cabo Gracias a Dios in the Bay of Honduras in 1711. They were unable to provide themselves with food or shelter and survived only because of the help of Miskito people. Uring described his experience in the book Voyage and Travels. In Chapter 4, “Painted Man,” Severin continues his exploration of the Miskito Coast as he describes adventures of pirates' surgeon Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America (1680s.) Together with a band of stranded pirates, Wafer undertook a strenuous journey from the Pacific to the Caribbean and lived for several years among Kuna people. Severin considers the possibility that Golden island in Caribbean Sea is the island described by Defoe. In the novel, Crusoe founded a successful colony on the formerly deserted island. Severin compares Defoe’s narrative with Wafer's colonial plans as well as with the tragic story of New Caledonia colony. In Chapter 5, Salt Tortuga, Severin reviews the story of Henry Pitman, who for three months was marooned on the Caribbean island Salt Tortuga, which is a part of a chain of islands off the coast of Venezuela. Two years later, upon his return to England, Pitman published a book about his adventures, A Relation of the Great Suffering and Strange Adventures of Henry Pitman, Chirurgeon (1689.) Severin points out many parallels between Pitman's story and Defoe's novel, starting with the title. Both Pitman and Crusoe start their adventures by enduring slavery and escaping under similar circumstances. Tortuga Island shares many features with the island described by Defoe, including the geographic location off the Orinoco mouth near the coast of Venezuela. Like Crusoe, Pitman occupies himself with making useful utensils, such as a cooking pot and a pipe, as well as with reading and writing. Other similarities include the presence of an Indian slave who is very skilled at fishing and hunting, and especially the circumstances of the final escape from the island which involves a skirmish with the pirates and the seizing of their ship. Severin travels on a sail boat to Tortuga and two other nearby islands. He also describes two extraordinary examples of survival in this part of the Caribbean. One of the survivors was a sixteenth-­‐century Spaniard, Pedro Serrano, who lived on an island with no fresh water and no vegetation for seven years. The other one was a fisherman, Andrew Powery, who in 1932 managed to swim a long distance to the Cayman Islands from the little island on which he and his friends were stranded after a hurricane. In Chapter 6, Crusoe Found, Severin comes to an important conclusion: Pitman was the prototype for Crusoe. An important clue for Severin was the last page of Pitman's book, which provides his address as "my lodging at the sign of the Ship in St. Paul's Churchyard, London, June the 10th, 1689." The title page of Robinson Crusoe also contains a reference to the publisher's address as being by "the sign of the Ship in Paternoster Row." Severin concludes that Pitman's publisher, John Taylor, was the father of William Taylor who later was Defoe's publisher. Furthermore, Pitman rented rooms at the premises of John Taylor. It is likely that William as a young boy listened to Pitman's stories and later shared them with Defoe or maybe gave him a copy of Pitman's book. It is also likely that Defoe knew both the Taylors and Pitman long before he wrote the book since in 1689, when Pitman's book was published, Defoe was a hosier and was selling socks in the same part of town.