Tarter cheetah

advertisement

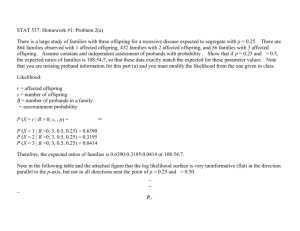

Title Evolution of maternal investment strategies for the Cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus, based on environmental risk factors. Author Jamison Tarter Abstract Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) are found in 26 countries of Africa and parts of Iran. Cheetahs are able to breed every twenty-one months, producing an average of four to five cubs per litter. Each cub is about 30cm long and weighs 250 to 300 grams. The mother hides the cubs for five to six weeks until they are able to accompany her on hunts. The number of cubs lost to predation and starvation was plotted to determine the risk management strategy used by the Cheetah. The calculations show that predators are a much greater threat to cub survival than starvation. Introduction The Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) is a terrestrial feline distributed throughout Africa and Iran. It is a mammal, belonging to the family Felidae. The adult cheetah weighs between 31-64 kg (68-141 lb), with the largest cat in captivity weighing 65 kg (144 lb). Females become sexually mature at approximately 20-23 months of age and have a lifespan of approximately 12 years in the wild. Cheetahs can have a new litter about every 21 months. This means they can have approximately 6 litters in their lifetime. Cubs measure up to 30 cm (11.8 in) long and weigh 250-300 grams (8.8-10.6 oz). Cheetahs eat young and large antelope, warthogs, springhare and game birds. Predators such as the lion and hyena are a major source of mortality for cubs, but not adults. The lifetime fitness goal of each sexually mature female, like the cheetah, is the survival of two sexually mature offspring to replace her and her mate. Given that most offspring perish before reaching maturity, how do mature females of any species—clam, insect, fish, frog or elephant—reach this goal? According to the maternal risk management model (Cassill, D. L., 2013), utopian environments favor investments in a few, low quality offspring, predation environments favor investments in offspring quantity, seasonal environments with periods of scarcity favor investments in offspring quality and multi-risk environments with high predation and periods of scarcity favor investments offspring diversity—usually a few high-quality offspring and many-low quality offspring. In this study, we measured offspring quality and quantity for the saltwater crocodile and then used these metrics to predict the environmental risk factors that shaped the evolution of maternal investment strategies. Method The number of offspring a cheetah can produce was calculated by first subtracting the number of years it takes to reach maturity (m) form the number of years lived (L) (reproductive time (R) = L – m). Investment time (IT) was calculated by adding gestation time (g) and time till mother leaves cubs (mc) together (IT = g + mc). Reproductive time (R) was then divided by investment time (IT) to determine the number of litters (nL) possible (R / IT = nL). Litter size (Ls) was then multiplied by number of litters (nL) (Ls x nL = Offspring total (Ot). Offspring number and relative offspring body-size were plotted on the inner “x” and “y” axes. The outer “x” and “y” axes are qualitative probabilities of predation or starvation. The relative body size of offspring at independence and thus the probability of starvation was estimated as S = m/M where S = expected probability of offspring mortality based on cycles of food scarcity; M = mass of mother at the time of offspring independence; mx = mass per offspring at the time of its independence. The expected probability of offspring mortality by predation was estimated as P = 1 – (2/N) where P = expected probability of predation; 2 = expected lifetime fitness per mother; N = the number of offspring produced by a mother per clutch or lifetime. The expected probability of offspring mortality in multiple-risk environments is estimated as PS. Results Offspring quality was estimated using 112 cm as the average length of offspring at independence (almost 4 times the birth length of approximately 30 cm). Maternal length was estimated as 125 cm. Relative offspring quality represents the probability of offspring mortality by starvation, which was calculated as 112/125 = 0.896. Offspring quantity was estimated at 29.28 cubs per reproductive lifetime. The probability of offspring mortality by predation was calculated as 1 – [7.91/29.28] = 0.73. To summarize here, the percent of offspring that will die of predation (73%) far exceeds the percent of offspring that will die of starvation (89.6%; Fig. 1). Figure 1: The maternal investment strategy by the cheetah is R. R: is a Multi-risk environment with high predation and periods of scarcity select for a few high-quality offspring and many-low quality offspring. P: Predation environments favor investments in offspring quantity rather than quality. S: Seasonal environments that cycle between abundance and scarcity favor investments in offspring quality rather than quantity. U: Utopian environments favor few, low quality offspring. Discussion The cheetah is a carnivore, feeding mainly on small prairie animals such as springhare, warthogs, game birds and large mammals such as the antelope. They have many adaptations that make them highly specialized for speed, such as a flexible spine, enlarged heart and increased lung capacity. They are able to reach speeds of up to 110 km/h (68 mph!!) and cover 7-8 meters (23-26 ft) in one stride! Cheetahs are a highly endangered species, it is estimated that only 10,000-12,600 are left in Iran and the African countries. On average 90 percent of cubs die within the first 3 months of life, either to predators like lions and hyenas or to starvation. Though highly preyed upon as cubs, adult cheetahs have no natural predators. Based on our calculations, we can deduce that the cheetah’s maternal investment strategy, investing more in offspring quality than quantity, evolved in an environment in which offspring had limited access to food, and were exposed to high predation. References Bertschinger, H. J., Meltzer, D. G. A., & Van Dyk, A. (2008). Captive breeding of cheetahs in south Africa – 30 years of data from the de wildt cheetah and wildlife centre. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 43(2), 66-73. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01144.x. Cheetah Conservation Fund. (2012). About the cheetah. Retrieved from http://cheetah.org/about-the-cheetah/ Defenders of wildlife. (2013). Basic facts about cheetahs. Retrieved from http://www.defenders.org/cheetah/basic-facts National Geographic. (2013). Cheetah. Retrieved from http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/cheetah/ Smithsonian National Zoological Park. (2013). Meet our animals: CHEETAH. Retrieved from http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Animals/AfricanSavanna/Facts/fact-cheetah.cfm Sunquist, M., & Sunquist, F. (2002). Wild Cats of the World (p. 29). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.