Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia

advertisement

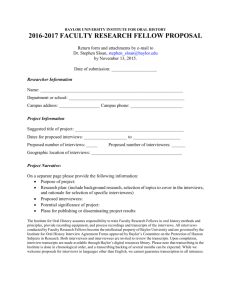

ISS PAPER 266 | SEPTEMBER 2014 Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia Anneli Botha and Mahdi Abdile Summary Effective counter-radicalisation strategies should be based on an empirical understanding of why people join terrorist organisations. Researchers interviewed former al-Shabaab fighters and identified a complex array of reasons for why they joined the organisation. Interviewers developed a profile of typical al-Shabaab recruits and identified factors facilitating their recruitment, including religious identity, socioeconomic circumstances (education, unemployment), political circumstances and the need for a collective identity and a sense of belonging. The reasons for al-Shabaab’s rise are discussed and recommendations are made to the Somali government, countries in the region and international organisations and donors on how to counter radicalisation and recruitment to al-Shabaab. THIS STUDY IS BASED on the belief Counter-radicalisation measures have in terms of the broad political that counter-radicalisation strategies proved to be ineffective and even socialisation process rather than from should be informed by a better counterproductive if they are not based the perspective of a single root cause, understanding of why people join terrorist on a clear understanding of what or conditions conducive to terrorism organisations. This understanding should causes individuals to be susceptible to that, although useful, are too broad. be based on empirical evidence and violent extremism. Because socialisation is a life-long not guesswork or analysis of completely There is no shortage of publications on different organisations in other countries the root causes of terrorism. However, process, the study considers a range of socialisation agents that affect the radicalisation process. or regions. Although such studies most concentrate on the broad contribute to a better understanding circumstances that motivate people to In order to gain insight into the of radicalisation, counter-radicalisation commit acts of terrorism and are radicalisation and recruitment strategies should be tailored to address therefore not always applicable. While processes that al-Shabaab recruits specific issues that explain why a acknowledging the influence of external in Somalia go through, the Institute particular type of person joins a particular factors, this study intends to explain for Security Studies and Finn Church organisation in a specific locality or radicalisation from the perspective of Aid collaborated to conduct this country. A single factor, such as poverty, individual, self-professed members of study. Southlink Consultants Ltd were can rarely be blamed for radicalisation. al-Shabaab. It will explain radicalisation commissioned to conduct fieldwork for the study from 14 to 28 April 2014 in Mogadishu, Somalia.1 Using local contacts, researchers were able to identify former fighters in a number of sites in the Mogadishu area, including internally displaced persons’ camps that are known to house many former al-Shabaab fighters.2 A total of 88 respondents were interviewed, while another seven interviewees, including two former members of Amniyat (alShabaab’s intelligence service), agreed to be interviewed off the record. Despite numerous challenges,3 the team achieved the fieldwork’s objective of generating empirical data about the radicalisation and recruitment process used by al-Shabaab. develop the ability to think ideologically,5 i.e. to politically identify with subgroups in society, which is a crucial step in establishing their political ‘selves’.6 During this period they also form ‘worldview beliefs’ that influence how they perceive, interpret, and respond to their social and interpersonal environments.7 Because they are not used to the realities of political and socio-economic participation, young people are more idealistic and reform minded, and are therefore impatient with the compromising methods of their elders and are therefore easily drawn into unconventional political behaviour.8 Instead of accommodation or Profile of interviewees manipulation (the favourite political tactics of the older generation), young people In keeping with its name, which means ‘The Youth’, al-Shabaab targets adolescents and young adults: only 9% of interviewees joined after their 30th birthdays (Figure 1). favour confrontation. Because they are particularly susceptible to influences during their mid-to-late teens, it is not surprising that it is during this period that Figure 1: Age at which interviewees joined al-Shabaab 45 40 40 35 % 30 25 25 20 21 15 10 5 88 THE NUMBER OF FORMER AL-SHABAAB FIGHTERS WHO WERE INTERVIEWED 7 THE NUMBER OF OTHERS INTERVIEWED OFF THE RECORD 2 0 1 4 <10 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 5 2 2 30-34 35-39 >40 It is important to note that during the period between puberty (ages 12–17) and early adulthood (18–22) people are at their most impressionable and most open to outside influence, because they are both becoming increasingly aware of the social and political world around them and simultaneously establishing their own identities and political ‘selves’.4 they are often radicalised and recruited. Individuals form their identities between the ages of 12 and 16, when they without a mother. What is particularly Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia Generally young people are particularly vulnerable to radicalisation for two primary reasons: their impatience with the status quo and their desire to change the political system – if necessary, through the use of violence. Among the sample group, 34% grew up without a father, while 16% grew up telling is the age at which interviewees lost their fathers or mothers: 23% lost It can be expected that an individual’s their fathers and 8% their mothers position in the organisation will have when they were younger than five, 68% a direct impact on the way in which lost their fathers and 69% their mother questions will be answered in interviews. between the ages of 16 and 18, while The majority of interviewees (60%) 9% lost their fathers and 23% lost their Radicalisation and recruitment Although a number of definitions of radicalisation are available, Gurr defines the concept as: categorised themselves as ‘fighters’ (see Figure 4), thus representing the A process in which the group has grassroots levels of the organisation been mobilized in pursuit of a social Most interviewees who lost a parent (Figure 3). The figures given in Figure 3 or political objective but has failed or both parents did so between early indicate how interviewees ranked their to make enough progress toward adolescence and early adulthood, at a position in al-Shabaab structures. Note the objective to satisfy all activists. time when individuals are particularly that it is possible that members of Some become disillusioned and vulnerable to losses of this magnitude. middle management and the higher discouraged, while others intensify At the other end of the spectrum, the echelons of the organisation would be their efforts, lose patience with majority of interviewees had a father more committed to al-Shabaab and its conventional means of political (66%) and mother (84%) present in ideals, which could form the basis of a action, and look for tactics that will future study. have greater impact. This is the mothers between 19 and 20. their lives. In terms of whether marital status and having children of their own at the time % 51 34 15 25 will decide to experiment with terror 20 tactics. The choice is made, and 15 justified, as a means to the original 10 ends of radical reform, group 7 3-4 5-6 7-8 0 dynamics of the process are such 9-10 that the terrorists believe that they enjoy the support of some larger community in revolt.9 70 vo rc ed W id ow er Ch ild r Si ng en le a ch nd ild re n rie d 2 60 Di M ar 1-2 autonomy, or whatever. And the 2 Figure 4: Interviewees’ roles in al-Shabaab 4 0 le make it likely that some activists Note: Rating on a scale of 1–10, where 1 indicates ‘lowest ranked’ and 10 indicates ‘highest ranked’. 20 Si ng 30 0 10 episodes of violence elsewhere) that 37 5 47 30 and rationalistic grounds (dramatic 35 60 % an expressive motivation (anger) 44 40 interviewees were single (Figure 2). 40 Impatience and frustration provide 45 on their recruitment, the majority of 50 or ‘imitative’ behaviour occurs. 50 of joining al-Shabaab had any impact Figure 2: Interviewees’ marital and parental status kind of situation in which modelling Figure 3: Interviewees’ position in al-Shabaab 60 50 40 % Although the majority were single, however, marriage and having children did not prevent interviewees from joining al-Shabaab. The relatively fewer married recruits should be interpreted together with interviewees’ age at the time of their recruitment, remembering that al-Shabaab tends to attract younger individuals. 30 20 10 0 17 2 6 Casual worker Collect money Fighter 3 5 Intelligence Recruiter Religious scholar 5 Security 2 Trainer ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 3 The duration and process of radicalisation differ from person to person, although it is commonly accepted that the process occurs gradually over a period of time. Conscious decisions to, for example, join a terrorist organisation or use violence for political ends are not made suddenly, but entail a gradual process that includes a multitude of occurrences, experiences, perceptions and role players. indicated that they would remain friends Having contact and listen to others with different opinions are important facilitators preventing radicalisation, because discussions with people with different opinions force people to constantly rethink and refine their own positions. On the other hand, sharing one’s opinions indicated a short period of between one with people who hold similar viewpoints will reinforce one’s position, identify common problems and provoke collective action.10 This form of isolation leads to ‘groupthink’, which can be described as an irrational style of thinking that causes group members to make poor decisions.11 With this in mind, only 9% of interviewees % 4 leaders, community members and friends. When asked how long the period was between being introduced to and joining the organisation, a large proportion (48%) and 30 days (Figure 5). This should be interpreted in terms of the primary reasons why interviewees joined al-Shabaab (Figure 7), i.e. religion and the economic benefits al-Shabaab offered. The short period between being introduced to and joining al-Shabaab might reflect an emotional and poorly thought through decision in which interviewees experienced two central emotions: anger and fear (Figure 6). Anger is probably one of the most common and powerful emotions event in an attempt to regain control and/ directed at those considered to be causing 48 it.12 According to Huddy et al.,13 anger is intensified when the responsible party is 31 perceived to be unjust and illegitimate. 10 16 5 1-30 days 2-6 months 7-12 months Anger seldom enables the person to reasonably evaluate the information 1-5 years surrounding its cause. Consequently, Figure 6: Emotion associated with joining al-Shabaab 30 25 26 24 18 15 10 10 2 em pt 5 Co nt lt d Ha tre Fe ar nd fe ar er a An g er ha and tre d An g Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia 2 G ui 5 0 H an atr d ed fe ar 5 ge r % 20 An The percentage of interviewees who indicated that they would remain friends with those they do not agree with (40%) referred to elders, parents, religious response to a particular circumstance or 20 9% indicated that they would listen to others or remove the reason for anger, and is 30 0 listen to friends’ advice. Interviewees who terrorism. This emotion normally occurs in 60 40 further 60% indicated that they would not associated with political violence and Figure 5:Period between being introduced to and joining al-Shabaab 50 with those they did not agree with, while a affected individuals are often unable to recognise additional threats that might contribute to unnecessary risk taking. They tend to resort to stereotyping, making them vulnerable to individuals attempting to convince them to respond,14 leading to hatred and the desire for vengeance. The Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy It is clear from Figure 7 that religious identifies ‘conducive conditions’ and economic factors were central to to terrorism. These ‘push factors’ explaining why interviewees joined al- or enabling circumstances include Shabaab. These factors, together with political circumstances, including the political circumstances in which the poor governance, political exclusion, decision to join the organisation was lack of civil liberties and human rights made, are discussed below. The level of frustration interviewees experienced was a relatively minor contributing factor: the majority (56%) of interviewees rated their levels of frustration at between 1 and 4 on a scale of 1–10 (with 1 indicating ‘not frustrated’ and 10 ‘highly frustrated’). Forty-two per cent referred to frustration levels of between 5 and 7, while only 2% rated their frustration levels between 8 and 10. The fact that the majority did not recall high frustration levels suggests that they either wanted to minimise their commitment to and involvement with alShabaab or were not driven to accept the cause it represented by frustration alone. sociological circumstances, e.g. abuses; economic circumstances; Mohamud (not his real name) was barely 14 years old when he joined religious and ethnic discrimination; counter-terrorism operations and their impact; and perceived injustice and international circumstances. Although a basic understanding of these conditions provides an insight into radicalisation, without pressure from domestic and personal circumstances individuals might support the ideas of extremists (nonviolent extremism) without becoming al-Shabaab. He was a schoolboy in Marka, and when the three-month long holidays approached in 2009, he was advised by friends to join the organisation. ‘When you join, they give you a mobile phone and every month you get $50’, he said. ‘This is what pushes a lot of my friends to join.’ actively involved in acts of terrorism Religious identity (violent extremism). Secondly, not all As explained in the discussion of people faced with the same set of the role of the family in radicalisation circumstances will become radicalised, (see ‘Political circumstances’, below), while not all of those who are radicalised political socialisation also include the Circumstances facilitating interviewees’ recruitment to al-Shabaab will join a terrorist organisation or commit development of a social identity as ‘part acts of violence and terrorism. of the individual’s self-concept which Radicalisation involves both external and internal factors. External factors can be subdivided into domestic and international circumstances, as presented in the United Nations Global CounterTerrorism Strategy.15 Internal or personal interpretations of the external environment are influenced by psychological factors that refer directly to political socialisation. individual who decides to join a terrorist Despite these circumstances, it is still the organisation or is drawn to the ideals and activities of extremist organisations. Ultimately one realises that human behaviour is extremely complex and that the key to radicalisation is the individual’s response to the circumstances described above. Interviewees identified the reasons why they joined al-Shabaab (Figure 7). derives from one’s knowledge of his or her membership in a social group or groups together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership’.16 This gives rise to a collective identity that Abádi-Nagy defines as ‘the set of culture traits, social traits, values, beliefs, myths, symbols, images that go into the collective’s selfdefinition’.17 Simon and Klandermans explain the importance of collective identity in an individual’s psychological Figure 7: Interviewees’ reasons for joining al-Shabaab makeup, stating that it: • Confirms the individual’s membership of 30 25 27 20 • Provides distinctive characteristics to 15 this group 7 4 us Re an lig d io fo us rc ed an R d elig ec io on us om ic an Re d lig pe io rs us on al Re an ligi o d u et s hn ic 3 • Ensures respect from those sharing the individual’s position in society io Re lig d 4 rc e no m Ec o tu re en 1 ic an Ec d on ad o ve mic nt ur e Pe rs on al 1 0 Fo 5 identify others who are not members of 15 13 10 Ad v % a particular group in society 25 • Leads to a sense of self-respect or self-esteem by providing understanding ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 5 of or meaning to the social world the individual is part of that they perceived Islam to be under • Provides a sense of solidarity with others and reminds the individual that he/she is not alone18 threat, interviewees referred to the In light of the above, it is significant that all the interviewees grew up in areas where Muslims were in the majority and that they had a very negative perception of religious diversity and acceptance of other religions (Figure 8). a religious figure. Despite this, the single Figure 8: Interviewees’ religious perceptions limited role of a religious figure in the recruitment process: only 4% of them were encouraged to join al-Shabaab by largest group (27%) were introduced to al-Shabaab at a mosque, implying the involvement of other individuals who used the space and opportunity for recruitment purposes. According to one interviewee, ‘preachers delivered sermons for hours about destiny and the sweetness of 100 100 80 the holy war. They distributed leaflets 97 97 96 on Islam, showed video recordings 97 from other jihadist in the world and 79 % In addition to the general motivation 60 how AMISOM [the African Union 40 crusaders invaded our beloved country Mission in Somalia] or the Christian and were converting our children to 20 Christianity.’ te re oth lig er io ns Ha Ac c re ep lig t o io th ns e (n r o) ry in re to lig ot io he n r (n o) ar Interviewees also came from a large number of ethnic groups or, in the Somali context, clans. M lig Re Re lig io us io n im m po os rta t nt d (n iver eg si at ty ive ) Re eq ligi ua on l (n s o) 0 This confirms not only al-Shabaab’s strong religious motivations, but links directly to interviewees’ perception that their religion (Islam) was under threat, which was the belief of a highly significant 98% of interviewees (Figure 9). This threat was often associated with nonMuslim countries. Ahmadey Kusow, a Somali-Bantu, joined the al-Shabaab voluntarily and became a loyal member of the group. He is one of hundreds of young men belonging to the Somali-Bantu and minority clans who have freely joined the militant group because they feel they have been marginalised since the collapse of the Somali state. They THE PERCENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES WHO PERCEIVED ISLAM TO BE UNDER THREAT 6 100 80 an opportunity to take revenge and tribes who grabbed their farming areas and (to some extent) property. 98 69 60 In addition to local Somali nationals, al- 40 29 20 0 say recruitment to al-Shabaab as empower themselves against majority 120 % 98% Figure 9: Interviewees’ perception that Islam is under threat 0 Islam under threat Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia Physical Ideological Physical threat threat and ideological Shabaab also attracts Somali nationals living abroad, other foreign fighters and nationals from neighbouring countries to join the organisation. Socio-economic circumstances Interviewees were asked to identify their most important reasons for joining al-Shabaab. While the majority referred to religion (see above), 25% combined religion with economic reasons, while a further 1% referred to economic reasons and the desire for adventure. These interviewees thought that al-Shabaab membership would become a career, which casts doubt on their ideological commitment to the organisation’s aims. One can possibly conclude, therefore, that if most interviewees had been given access to other employment opportunities, they would not have joined al-Shabaab. Education Education is identified as crucial to preparing young people to obtain employment. Education can also counter later radicalisation, because better- • They feel that they can influence the political process more than lesseducated people because they can articulate their opinions better • They are more aware of the impact of government on their lives • They generally have opinions on a wider range of political topics. They are also more likely to engage in political discussions with a wide range of people, while the less educated are more likely to avoid such discussions Figure 11:Interviewees’ school leaving age 60 50 52 46 40 % educated people tend to participate in conventional politics, for various reasons: 30 20 10 0 2 98 7-9 10-14 15-19 Interviewees also identified education and employment as two central components of attempts to find a solution to Somalia’s problems, together • Educated people are more likely to have confidence in the political process and be an active member of a legitimate political organisation19 with peace, stability, reconciliation, etc. The unfortunate reality in Somalia is that the formal education system came to a standstill when the Somali state collapsed in 1991, leaving an entire generation uneducated: 40% of interviewees received no education, while the remaining 60% received only limited education (Figure 10). Higher levels of education also (Without these latter attributes, education and sustainable development will remain an illusive dream.) decrease individuals’ propensity to engage in civil strife.20 Ultimately, the solution to radicalisation is not education as such, but the quality and type of education provided. Students need to learn from other disciplines, such as the social sciences, history and philosophy, that can equip them Figure 10: Education received by interviewees to be open to other opinions, to argue 50 intelligently, and to understand domestic 45 40 35 % Abu Aisha came from the United States and joined al-Shabaab after being recruited through the Internet. He fought for three years, but became discouraged by the way in which jihad was conducted. He was among a handful of Somali-Americans who had drifted to al-Shabaab over the years. A number of recruitment agents and support networks have been uncovered in the United States that approach potential targets through mosques, the Internet and community contacts. The Englishlanguage skills and social disconnect of Somali-Americans may be assets to al-Shabaab. Due to both the trauma experienced by recruits’ parents when fleeing Somalia’s long period of anarchy, and cultural and economic problems they encountered when attempting to integrate into US society, some angry teens have become fertile targets for al-Shabaab recruitment. and international realities. 43 Unemployment 40 30 Lack of education adversely affects 25 employment opportunities. Self- 20 employment is an option when formal 15 employment opportunities are limited, but lack of education is a limiting factor here 10 9 5 0 8 too. In a study conducted in Uganda, Tushambomwe-Kazooba showed that No education Private Religious Private and religious The majority of interviewees who received a religious education or attended a madrassa recalled the level of focus on the Qur’an. Of those who received some form of education, the majority left school between the ages of 10 and 14 (Figure 11). the majority of new business owners were not properly trained, leading to poor business planning and management decisions.21 In an attempt to assess the potential role unemployment plays in radicalisation, interviewees’ employment levels are summarised in Figure 12. All those who were employed had low-income jobs, largely because they ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 7 Figure 12: Interviewees’ employment status fighter and was killed in 2011. Amina reported that she still bore the scars 60 50 49 from severely beatings she suffered 50 when she tried to escape. Eventually % 40 she pretended that her mother was 30 ill and fled into the bush when the 20 guards were praying as she was 10 0 1 Employed Unemployed Student being escorted to see her mother. ‘I was later rescued by herders who assisted me with a change of clothing did not have the education needed to before I ended up in Mogadishu’, she obtain better jobs. It was therefore not told the interviewer. surprising that interviewees who defined adverse economic circumstances as a recruitment factor saw al-Shabaab as Political circumstances a potential employer, claiming that they As discussed above, prior political were paid between $150 and $500 experiences are an important indicator of per month. the extent to which people trust politicians and the political system. This starts at the Amina (not her real name), a widow, was brought up in Burhakaba. Her parents were staunch Muslim farmers and herders. In 2004 she married a farmer from her clan and had two children. In 2009 her husband was approached by several young men who claimed to represent al-Shabaab. He was told to join and fight for his people, community and religion against their external in families where politics is discussed or where parents are interested in politics are more likely to see the value of participating in the political process. This extends to peer groups, in which the level of political discussion will mirror group members’ sense of political efficacy. Finally, actual events will impact on individuals’ political socialisation and contribute to their political perceptions and values. enemies and infidels. ‘We will protect The family serves as a child’s first you and once you join we will pay introduction to the political culture you $300 per month’, they told him. of his/her country. Despite Somalia’s Amina feared for her husband’s life violent past, only 17% of interviewees when they threatened him later. indicated that their parents discussed She and her husband later yielded politics in their presence while they were to the coercion and decided to join growing up. Asked if they agreed with the group. They were paid $300 for their parents’ political opinions, only 7% the first few months, but later were answered in the affirmative. This limited informed that they would not be paid political interaction between parent and and had to work hard and fight for child reflects a generation gap, and could the sake of Islam if they wanted to go be extended to the possibility that the to heaven. Amina cooked, washed ideology al-Shabaab represents is not clothes and collected firewood in historically embedded in Somalia and PER MONTH the presence of guards, while her that parents fear any form of political husband first inspected roads before discussion with their children. This was AMOUNT INTERVIEWEES WERE PAID BY AL-SHABAAB becoming a fundraiser working in reflected in the fact that only 5% of $150 – $500 8 family level in that children growing up nearby villages. He later became a Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia interviewees indicated that a parent was aware of their decision to join al-Shabaab. the organisation. Secondly, only 3% of interviewees indicated that they had joined with family members, while 3% recruited family members to al-Shabaab. The reality is that if the family is unable to transfer its political orientations to its younger members, other socialisation agents are likely to be more influential. The role of friends in interviewees’ decision to join the organisation was unmistakable: friends introduced 30% of interviewees to al-Shabaab, while 22% of interviewees stated that they had recruited other friends. Friends were also the largest group (42%) that interviewees informed of their decision to join the organisation. This is because the family’s influence wanes at 13 or 14 years of age (note that 40% of Figure 13:Influence of friends and family on interviewees % participates in specifically political affairs.22 The fact that the majority of interviewees joined with friends testifies to peer pressure, but it also affects how interpersonal relationships should be is based on two key pillars: the emotional link between the individual and the peer group, and the access the individual has 20 22 3 3 Joined Joined Joined Recruit- Recruitwith with alone ed ed friends family family friends without the experience of an effective political system, despite various attempts to consolidate political power following the collapse of the Siad Barre regime in 1991.23 Figure 14: Interviewees’ political experiences and perceptions 90 80 70 old and was born and brought up 60 in Baidoa, but is currently living in 50 Mogadishu. He was 20 years old % Abdi (not his real name) is 24 years 30 youth who are desperate for the 20 ever-illusive source of a livelihood. 10 Abdi was approached by a friend 0 who was already an al-Shabaab member. Initially shocked, having been engaged in social activities that al-Shabaab did not permit, Abdi 82 69 40 and was idle, just like many Somali 39 17 7 2 rejected the idea, but later joined the group after being persuaded by his friend. After joining, he was instructed to abandon his lifestyle of smoking and chewing miraa, which he found difficult, earning him several punishments. He escaped several times, but was caught and returned to the al-Shabaab camp. To retain him, the camp elders supported his habits and bought him cigarettes and miraa. He became an informer and a link with local farmers, from relocated to Kismayu before travelling 33 In Somalia, an entire generation grew up to the group, and vice versa. him $250 a month. He ran away and 30 Interviewees’ experience of politics interpreted. The strength of peer groups group reneged on its promise to pay 40 0 begins to take a more active interest and Abdi finally left al-Shabaab when the 64 50 10 This is also the period when the individual who he used to collect $50 a month. 70 60 the ages of 15 and 19; see Figure 1). sc p us Ag olit s re ics e jo V p wit in o ar h in te en g d al- b ts Sh efo r Tr aba e us ab te Tr ld us er s tp ol itic El ec i tio ans ns b ch rin an g ge In addition to the relatively limited involvement of their parents in interviewees’ recruitment by al-Shabaab, siblings played the smallest role, introducing only 2% of interviewees to interviewees joined al-Shabaab between Di Only 3% specifically informed a parent of their joining the organisation, while 3% informed another sibling. To put these figures in context: 57% of interviewees informed another person. It is therefore improbable that family members agree with al-Shabaab’s ideology or even accept it as the norm. Parents of interviewees clearly played a lesser role in transferring their political orientations to their children through the socialisation process. Instead, peers played a greater role in interviewees’ political socialisation, which will be discussed below. to Mogadishu. Almost a year since leaving the group, Abdi still lives in fear that once one joins al-Shabaab, it is very hard to walk away from it. When asked whether they trusted politicians and the political system, 39% of interviewees indicated that they trusted politicians (Figure 14). In contrast, 82% trusted clan elders, while a further 69% trusted the political process to bring about change, despite the fact that only 2% had participated in the election process before joining al-Shabaab. Interviewees’ trust in elders is a positive finding that the Federal Government could build on. However, 18% of interviewees believed that elders were only looking after their own personal interests and that of close family members. When asked whether they thought that elections would bring about change, 37% of interviewees did not consider elections to be ‘free and fair’, while a further 55% did not consider elections to be ‘free and fair’ and believed that they ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 9 were not able to register a political party that represented their ideas. situations, collective identity might Despite positive perceptions that elections can bring change, the vast majority of interviewees agreed with the statement that ‘government only looks after and protects the interests of a few’. When asked whether ‘opposing the government is legal and just’, only 4% did not agree with this statement (Figure 15). • When individuals are increasingly Figure 15: Interviewees’ views on the government • When they are confused by social and political chaos around them • When they feel threatened by another group In an attempt to address these circumstances, individuals will turn to an ideological movement to provide ethnic or political group. In Somalia al-Shabaab presents Islam as the 97 % and/or their families their identification with a religious, 98 97,5 single overarching factor that binds 96,5 all the different clans together and 96 96 95,5 95 unable to provide for themselves them with an identity or will enhance 98,5 98 become more prominent: provides a solution to years of social and political upheaval. That being said, Government only protect own interests Revolt is legal it should be stressed that although religion serves as a nation-building factor, al-Shabaab does not represent From interviewees’ answers, it is clear Islam as such, but rather a particular that politicians and the government face interpretation of Islam as a solution to a serious legitimacy crisis. In other words, Somalia’s problems. if the government wants to present a meaningful option to unconventional political participation, it needs to meet people’s expectations. Most interviewees referred to the government’s duty to provide safety and protect people’s rights, while a few also included the responsibility to govern (in terms of their perceptions of what this meant). 82% THE PERCENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES WHO TRUSTED CLAN LEADERS 10 Collective identity manifests in the way in which individuals categorise people in terms of concepts such as ‘us’, ‘we’ or ‘ours’ when referring to the in-group, versus ‘they’, ‘them’ or ‘theirs’ in terms of the out-group or ‘enemy’. In Somalia, even among interviewees who stated that they were forced to join the organisation, al-Shabaab managed Collective identity and a sense of belonging to establish itself at the centre of A sense of collective identity can be grouped al-Shabaab and being easily politicised if the majority of the in- Muslim in the same category (‘us’) group share their feelings of injustice or and saw al-Shabaab as the defender inequality and thus turn ‘my grievances’ of Islam against other religions (with into ‘our grievances’. The next step is to specific reference to Christians) and identify the ‘other’ or out-group that can other countries (‘them’). It was also be blamed for these grievances, leading unsurprising to note that no interviewee to its stereotyping. Consequently, when referred to a Somali national identity or the individual is faced with particular ‘Somalis’ (Figures 16 and 17). Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia its members’ terms of reference. Fifty-eight per cent of interviewees Figure 16: Interviewees’ perceptions of ‘us’ Figure 18: Interviewees’ perceptions of al-Shabaab 70 60 58 100 80 30 % 40 30 30 al- 0 17 9 23 Figure 19: Interviewees’ sense of belonging in al-Shabaab 80 ar e re d a sp n ec d te Th d e so lu tio n Ar m re ed sp = ec alt S m hab y a ‘fa ab m ily Id al- ea ’ Sh ls ab of aa b aa alb a n Sh d ab M a al- usl ab an Sh ims d ab So aa m b a So lis m ali s 0 ab s 1 Sh lim ily m us M Fa 60 20 11 0 0 94 40 20 10 99 70 Fe % 50 of interviewees were low-ranked alShabaab members motivated by the promise of financial gain, while the small percentage that rated a sense of belonging higher had presumably been socialised as committed members of the organisation. 60 73 68 Figure 17: Interviewees’ perceptions of ‘them’ al-Shabaab for only economic reasons referred to the organisation’s religious 60 ideals and being Muslim and/or al- 55 50 40 Shabaab members as ‘us’ and other 30 religions and countries as ‘them’ (Figures 27 20 18 10 0 go So ve m rn ali m en t 0 16 and 17). O re the lig r O io th ns er co an u d ntr re ie gi s on G ov s ot e h rn an er r me d elig nt co io , un ns tri es % However, all the interviewees who joined Asking interviewees to rate their sense 40 30 27 27 20 10 0 0 1-4 5-7 Joining 5 8-10 Member Note: Rating on a scale of 1–10, where 1 indicates ‘least’ and 10 indicates ‘most’. of belonging when they joined and as members of al-Shabaab showed interesting results. Over time the sense of belonging increased slightly for some interviewees, although a large majority In addition to the reason why interviewees joined al-Shabaab, it was equally important to assess their perceptions of the organisation (summarised in Figure 18). It is clear that only a small percentage of interviewees were completely integrated into the organisation or truly believed in alShabaab and what it represents (23%) or regarded al-Shabaab as being the solution to Somalia’s problems (17%). Instead, the majority of interviewees were drawn to al-Shabaab because it is feared and respected (99%), and the fact that when they as individuals are armed they are respected (94%). To place this in perspective, it is important to remember that the overwhelming majority of interviewees were foot soldiers, not commanders, who joined because of the economic opportunities al-Shabaab potentially provided. % 50 indicated a very low sense of belonging in both scenarios (see Figure 19). What made these results interesting is that 30% of interviewees when asked to This sense of belonging was also emphasised when interviewees were asked to define ‘us’. The role of religion combined with al-Shabaab membership confirms that the interest of the collective – based on religion – serves as the most important component of members’ identities. For the majority of interviewees identity ‘us’ referred to al-Shabaab, whereas the majority (58%) referred to being Muslim and being members of al-Shabaab. These results measure the extent to which the individual identifies these two are seamlessly interwoven. In this regard, self-categorisation theory predicts that ‘people are more inclined to behave in terms of their group with the group and thus measures membership because their common solidarity within the group. This will have identity as a group is more salient’ when an impact on socialisation and group they are under threat. Consequently, any identification, which Janis describes as threat to the in-group will be interpreted ‘a set of preconscious and unconscious as a threat to the individual.25 Some attitudes which incline each member to interviewees indicated that their sense of apperceive the group as an extension of belonging slightly increased the longer himself and impel him to remain in direct they were members of al-Shabaab. This contact with the other members and confirms that over time the identity of the to adhere to the group’s standards’. organisation becomes the identity of the The apparent discrepancy between the individual, as suggested by Post26 and responses discussed above could be supported by Taylor and Louis,27 and that explained by the fact that the majority belonging to a terrorist organisation such 24 ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 11 as al-Shabaab can result in a collective as Iraq and Palestine, the presence of identity where individual identities are ‘infidels’ in Somalia, and the protection of replaced by a sense of being part of Islam. A further 11% indicated that they something bigger. were forced to join al-Shabaab or did so out of fear. The level of indoctrination the individual has been exposed to also influences Joining an organisation is the first step; the extent to which he/she internalises a more important issue is why members the relevant social and cultural values of stay. Figure 20 summarises interviewees’ that group through socialisation, leading most predominant reasons for staying to ‘collective conditioning’ as a form of in al-Shabaab. Although economic indoctrination. When an individual reaches circumstances were a prominent reason this state in his/her social identity, he/she for joining the organisation, Figure 20 will start to think in terms of the collective indicates that a sense of belonging and and completely identify with the group.28 responsibility were the main reasons why interviewees stayed in al-Shabaab. Catalysts for joining al-Shabaab In a follow-up question, interviewees were asked if they had any regrets While radicalisation can occur over a about their links with al-Shabaab, as long period of time, affecting not just presented in Figure 21. The majority of individuals, but entire populations, often a interviewees (42%) indicated that their single event or catalyst finally completes greatest regret was joining al-Shabaab the radicalisation process. Such a and getting caught by AMISOM and the catalyst is seen as relevant to a particular Somali authorities. Together with the situation and can occur on the micro 19% who indicated that their greatest or macro levels, or possibly cover both. regret was getting caught and another Whatever the case, it is traditionally an 5% who regretted not having recruited extreme or volatile event. When asked to more people to al-Shabaab, this indicates indicate what finally ‘pushed’ them to join that interviewees were more socialised al-Shabaab, the majority of interviewees into the organisation than at first seemed (39%) referred to economical reasons apparent. The 33% of interviewees whose specifically or in combination with other greatest regret was joining al-Shabaab circumstances, while 20% referred to the joined for personal reasons while not persecution of Muslims in places such committing themselves to its ideals. Figure 20: Why interviewees stayed in al-Shabaab 25 20 21 12 11 13 11 8 5 6 6 4 1 5 2 Fe ar Be lo ng in Re g sp on sib Be ilit lo y n g re in sp g on an sib d Be ility Be an long d in lo m g ng on in e g an y d Re fe ar sp Be on a lo s n d ibi n ib ging mo lity ilit , n Be y a res ey lo nd po ng m ns in on g, ey Re an res d pe sp m ct ec on ta ey nd m on Fe ey ar an d m on ey ey 0 on The percentage of interviewees who stayed in al-Shabaab because they felt they belonged 12 10 M 21% % 15 Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia Figure 21: Interviewees’ sources of regret regarding their joining of al-Shabaab 45 40 42 government officials, gather information to gather accurate intelligence, plan on agencies and donors funding these attacks, and operationalise such plans in agencies, and track scheduled visits by both Somalia and the wider region. The foreign partners and donors. planning and execution of the Kampala restaurant bombing, the daylight attack 35 30 % Today al-Shabaab has the capability on the Westgate mall in Nairobi and the 33 25 siege of the UN compound in Mogadishu 20 demonstrates such capabilities, which 19 15 30 10 5 1 5 Ch an g ta ed ct ics al- Jo Sh ine Di ab d aa m dn or ot b e re m c em ru be it rs G ot ca ug ht Jo in go ed t c an au d gh t 0 Possible reasons for al-Shabaab’s success the Somali government seems to lack. Thirdly, according to these sources, alShabaab uses clan and family networks to recruit informers who are usually close relatives, friends and family members of targeted individuals. According to the former Amniyat operative, information on Secondly, al-Shabaab uses coercion, UN agencies, foreign embassies, donors intimidation, bribery and outright murder and international organisations to collect information, forcing many are collected by targeting their staff or people to cooperate from fear of being close family and friends of a particular killed. According to one former Amniyat staff member. operative, such cooperation has been vital in al-Shabaab’s ability to collect crucial information and identify targets. According to this informant, al-Shabaab Over the course of seven years alShabaab has transformed itself from a rag-tag militia attempting to overthrow the Western-backed government and force the withdrawal of African Union peacekeepers to a fully fledged army that was able to conquer, control and administer most of southern and central Somalia for a lengthy period. Even after it withdrew from Mogadishu and several other regions, al-Shabaab continued to wage an aggressive war in key locations. is coercing many senior staff of the It was able to do this for several reasons. Firstly, unlike the Somali government and the international community assisting it, their families, and businesspeople who largest telecommunication companies in Somalia to provide information such as phone numbers, email addresses, and the residential and business addresses of individuals and groups under alShabaab surveillance. Fourthly, al-Shabaab uses unsophisticated tracking and surveillance techniques to monitor and access targets. The clan system plays a major role in this process. Family members, close clan members and friends are used to issue threats or facilitate collaboration. Tracking and surveillance are mostly done via phones. Through these techniques a personal profile of the targeted individual is built up covering things like his/her daily Targeted individuals are Somali routine, the layout of the target’s home, government officials, parliamentarians, their security arrangements, whether they UN staff members, the donor community, are armed, etc. local and international organisations, local staff working for these organisations and have business ties with these entities. Refusing to cooperate or exposing those Fifthly, foreigners and especially Kenyans play a leading role in al-Shabaab intelligence operations and planning. Informants claimed that most foot soldiers and middle commanders on the battlefield are Somalis, but almost all intelligence Al-Shabaab has invested heavily in its intelligencegathering capabilities analysts, middle and senior managers are better educated, more experienced and well-connected foreigners. Corrupt security officials and sympathetic al-Shabaab has invested heavily in its seeking such information could put those businesspeople and individuals are used intelligence-gathering capabilities. The who are forced to supply this information to pay for logistics and provide access to establishment of its intelligence service and their families at risk. According restricted areas. unit, Amniyat, some years ago may have to another source, al-Shabaab has looked like a shift in the organisation’s infiltrated approximately 150 of its agents tactics, but interviews with former al- into the Somali intelligence services, Conclusion and recommendations Shabaab fighters indicated a deliberate police, army and other government This study has examined the vulnerability strategic attempt to modernise the agencies. This allows the organisation of young people to being recruited by organisation’s operations and planning. to monitor the movements of senior al-Shabaab; the radicalisation process; ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 13 and radicalised al-Shabaab members’ perceptions of government, religious identity and external role players. The Somali government and its security forces, governments in the region (especially that of Kenya), and donors and international agencies can develop specific, tailored strategies to address the factors behind radicalisation as identified in this study. Recommendations to the Somali government and security forces Instability in Somalia was initially motivated by clan politics and the inability of leaders to build an inclusive Somali state. Al-Shabaab has managed to gain a foothold in the various clans, while areas recovered from al-Shabaab to different ideas to counter ‘group think’ and later possible radicalisation. Somalia still has a long way to go to effectively govern the areas it controls. While governance and providing essential services are crucial to securing popular trust and support, none of this will be possible without security. The following is recommended to the Somali security forces: 1. Intelligence-led operations. From the above analysis, it is clear that al-Shabaab’s strength rests on its intelligence-gathering capabilities, while the Somali security forces and AMISOM lack such capabilities. Intelligence is the core of any counter-insurgency programme: without proactive intelligence those The Somali government needs to establish partnerships with clan leaders and urgently initiate a nation-building strategy control once again show signs of conducting counter-insurgency falling back into the devastating reality operations are literally blind. The of clan-based politics. For Somalia to security forces should both develop recover, the Somali government needs to intelligence assets among the public establish partnerships with clan leaders and use technology in the form of and urgently initiate a nation-building ground radar and sensors, aerial strategy. In this regard it is important to recognise that those interviewed for the present study said they trusted clan elders more than politicians. An inclusive strategy that recognises the importance of Somali’s clan system should therefore be developed. Education and skills are key components Education can play a key part in countering radicalisation 14 reconnaissance (through unmanned aerial vehicles) and the interception of communications. Without proper intelligence-gathering capabilities, security forces often resort to force to obtain information from civilians. With good intelligence, operations can be directed at those behind the insurgency, without targeting of securing employment, which in turn civilians or those not involved in can break the cycle in which joining the insurgency. al-Shabaab and similar organisations is 2. Counter-intelligence. The other side the only viable option individuals have of intelligence gathering is counter- to provide for themselves and their intelligence, i.e. the capacity to families. Being at school also provides an prevent al-Shabaab from infiltrating opportunity to introduce young people the government and its security Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia forces. The vetting of new and existing members of the security forces should be the first step, followed by the investigation of potential security risks. In light of al-Shabaab’s intelligence-gathering capabilities, government security forces urgently need training on personal, physical and information security. 3. Building trust through ‘winning hearts and minds’ while enhancing control. Since popular support is considered to be a force enhancer, winning back popular support is considered a central component of any effective counter-insurgency strategy, i.e. ‘winning hearts and minds’. The most effective way to counter al-Shabaab is to show ordinary people that the government offers a better life than the one they experienced under al-Shabaab’s control. The problem is that people are being convinced by actions, not words, i.e. how the government and government representatives (especially the military and police) conduct themselves. The smallest incident in which the security forces are seen to abuse their power can break down trust. Avoiding such incidents calls for enormous discipline and a sense of responsibility that does not always a particular person or office, leading to the inability to see the bigger picture, which requires information to be shared. Another problem is resources allocation. Not being equally resourced will affect how these agencies view and work with one another during joint operations. In summary, rivalry and poor working relationships among security agencies will continue to affect the quality of cooperation for as long as the mandate of each agency is not defined by law and training and remuneration schemes differ among the agencies making up the security apparatus. return the situation to ‘normal’ so that 5. Transferring authority from the military to the police. Understandably, the military initially takes the lead in defeating al-Shabaab, but successful counter-insurgency operations require authority to be transferred to a civilian government and the police as soon as possible. This is easier said than done in a country that needs to rebuild the most basic of its institutions following decades of instability. Although the military is often associated with counter-insurgency operations, the police are better equipped to deal with insurgents in an urban setting (supported by the military) and in ‘liberated’ areas generally. • Securing and protecting key facilities the police can take lead, the military can and where necessary should be called in as a force enhancer and/or to support the police. These situations might include the following: • Assisting in the arrest of suspects expected to resist arrest, especially if they are well armed • Supporting the police in search operations • Providing logistical support • Controlling crowds during urban unrest • Providing advice to the police For this to be successful political will is needed to both enable the police and equip them with the necessary resources to carry out their functions properly. 6. Minimal use of force. Because injury and death among the civilian population hurt the overall objective of counter-insurgency operations, which is to win the hearts and minds of the public, force should be used with great care, particularly in urban settings, and only insurgents/terrorists should be targeted. In other words, both the come naturally to security force members after years of instability. 4. Coordination and cooperation between security agencies. Competition and rivalry within Successful counter-insurgency operations require authority to be transferred to a civilian government and the police as soon as possible and among government security agencies hamper their cooperation Trained to interact with the public military and police need to respond and coordination, threatening the and solve crimes, the police are in a appropriately to the actual and not the better position to isolate insurgents perceived threat they face. government’s ability to address threats to security. Personal differences between colleagues in security through cooperating with the public 7. Rule of law. The overall objective of – keeping in mind that the abuse counter-insurgency operations is to often make them unwilling to share of power and the use of force will re-establish the rule of law so as to information. Trust or its lack has the harm the overall objective of counter- allow society to function properly. To same effect. Another challenge is the insurgency activities. Although the achieve this the following should occur perception that information belongs to overall objective of such activities is to as soon as possible: services and intelligence agencies ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 15 • Security operations need to move from combat operations to law enforcement as soon as possible • When police take control insurgents should categorised as ‘criminals’ and not ‘soldiers’. In this way al-Shabaab will lose its remaining legitimacy • The capacity of the police, judiciary and penal facilities to provide people with justice should be enhanced, since this is a core element of securing lasting peace • Accurate record should be kept of all actions taken against insurgents and all offences committed by insurgents. These records can be used in later court proceedings show them that the police are there for them and with them • A police presence will not only improve public security, but will secure support for the government through their law-enforcement actions • If they are in daily contact with the public, the police will be able to collect information on al-Shabaab fighters attempting to merge with the public • If the police build trust among the public and present themselves as part of the public, security will follow • The police should protect all citizens irrespective of the clan to which they belong It is clear that strategies based on mass arrests and racial profiling are counterproductive The unfortunate reality in countries confronted by insurgencies is that the police are often one of the most poorly managed state organisations and are insufficiently equipped, poorly trained, deeply politicised and chronically corrupt. It is therefore essential that measures be taken to enhance the capacity of the police in Somalia to carry out the presence of Kenyan nationals in alShabaab’s higher echelons. This confirms earlier assessments that al-Shabaab has successfully presented itself as a jihadist organisation beyond the borders of Somalia and that it is not exclusively staffed by Somalis. It is therefore • The police should have the power to essential that security agencies in arrest criminals and investigate criminal Kenya and other countries of the region offences. It is therefore essential that move away from the perception that • The police should be visible day and night as the most noticeable ‘face’ of government: •Police stations should be established 16 Many interviewees referred to the following key functions: assistance addresses these functions The police should protect all citizens, irrespective of the clan to which they belong Recommendations to the region, especially Kenya only Somalis and Somali-Kenyans are involved with al-Shabaab. It is also clear that strategies based on mass arrests, racial profiling, etc. are counterproductive. Additionally, police- and intelligence-led criminal around the country, including in justice responses to terrorism are more volatile areas. However, the police effective than an arbitrary and hard- officers staffing these stations should handed response. While Kenya’s security not stay behind their walls, but forces (the police and military) have should interact with the public and experienced constant attacks since the Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia country’s intervention in Somalia, the consequences of blind retaliation are severe. Fighting an often-unidentifiable enemy who uses the anonymity of the masses to hide among, strike and then disappear is extremely frustrating. could emanate internally from staff willingly collaborating with these groups or being coerced to do so • Support the development and • Careful background checks should be conducted when recruiting new staff • Support an inclusive nation-building implementation of reintegration and counter-radicalisation strategies process, e.g. create opportunities for national dialogue initiatives that bring clan leaders together at Careful background checks should be conducted when recruiting new staff the national and regional levels to debate, make recommendations and agree on critical matters affecting the country However, lashing out against the • Vulnerability assessments should be collective is not only ineffective, but is carried out with great care, because also counterproductive, because there they could alienate some staff or be is a real danger that non-radicalised seen as discriminatory members of affected communities might feel the need to defend themselves against the ‘other’, thus ‘driving’ individuals to extremism. 3. Develop a strategy for assisting staff on the fringes of society as the ‘enemy’, International organisations with large but also the broader Kenyan community, number of local staff could consider which is driven by a well-established establishing secure guest houses perception that al-Shabaab only for local staff. (Most international consists of Somali nationals or those organisations and donors do not who are visibly Muslim. In light of this, usually pay much attention to local staff, but this is a major vulnerability Paper 265. staff member is considered to be most risks posed by al-Shabaab and other extremist groups are generally external, significant risks Inter-Governmental Authority on Development and the Eastern Africa Police Chiefs Cooperation Organisation • Ensure that people are trained in the right skill sets, while respecting the overall objective, i.e. that of establishing a responsible government and security apparatus that have the interests of all Somali citizens at heart Notes 1 This study is based on research for author Anneli Botha’s doctoral thesis in the Department of Political Studies and Governance at the University of the Free State entitled ‘Radicalisation to commit terrorism from a political socialisation perspective in Kenya and Uganda’. The thesis focused on al-Shabaab and Kenya’s Mombasa Republican Council, as well as the Allied Democratic Forces and Lord’s Resistance Army in Kenya. 2 Initially, the data collection exercise targeted a sample of 80–100 former fighters who were captured on the battlefield and were housed in the Sarendi Rehabilitation Centre in Mogadishu, a Federal Government facility. A second potential source of interviewees included government prisons in Mogadishu future actions • As highlighted in this study, although through regional actors such as the clan or family member who would be should: come from within the organisation: • Coordinate efforts, most notably bring his/her clan elder or an influential Donors and external organisations reduce risks, because threats could these realities ‘on the ground’ vulnerable, he/she could be asked to responsible for the staff member’s 2. Assess staff vulnerabilities in order to develop a list of priorities based on 4. Consider using the concept of clan security when hiring local staff. If a their local staff • Assess what is really needed and that is worth investing in.) radicalisation in Kenya please see ISS 1. Develop a regular screening policy for capacity-building initiatives in the country. needs, these actors should: if a staff member lives in a known alassist them to relocate to safer areas. Recommendations to donors and external organisations actors are offering training and other coercion and threats. For example, and its security forces that treat people of urgency. For more information on international community and regional Due to the magnitude of Somalia’s Shabaab stronghold, encourage and be implemented in Kenya as a matter relations with Somalia, both the who are vulnerable to al-Shabaab It is, however, not only the government nation-building programmes need to In addition to establishing diplomatic 5.Play a vital and active role in addressing vulnerabilities identified in this study. For example, donors could help to address the shortfalls highlighted in this study, such as: • Education and skills development • Employment opportunities for youth • The insecurity and vulnerabilities affecting ordinary Somalis ISS PAPER 266 • SEPTEMBER 2014 17 that host recently captured al-Shabaab fighters. However, due to the restructuring of the Sarendi Centre and the departure of key personnel, access to both the centre and prisons was not possible, so other methods of locating former al-Shabaab combatants were used. 3 4 5 6 The first challenge was the prevailing insecurity in Mogadishu. This general problem was exacerbated by the nature of the fieldwork – targeting former al-Shabaab fighters. Locating and interviewing such people proved to be one of the most dangerous undertakings in Mogadishu due to al-Shabaab’s highly sophisticated and efficient structure and operations. The second challenge related to ensuring that interviewees safely reached the place where the interviews took place and returned home afterwards, while there was always the threat that interviewees could be targeted for revealing information about al-Shabaab to its enemies. The third challenge consisted of logistical constraints and securing interview sites – no hotel or restaurant would allow former alShabaab fighters to be interviewed on their premises. Also, data collectors faced security threats such as the possibility of being followed and traced to their hotel, ambushed, or kidnapped. Also, on occasion sections of roads in Mogadishu were blocked for security reasons. The use of alternative ways of locating interviewees when initial plans did not work reduced the impact of the challenges on the overall results. DO Sears, and S Levy, Childhood and adult political development, in DO Sears, L Huddy and R Jervis (eds), Oxford handbook of political psychology, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, 83. Preston, Introduction to political psychology, Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004, 80. 12 Ibid, 50. 13 L Huddy, S Feldman and E Cassese, On the distinct political effects of anxiety and anger, in WR Neuman, GE Marcus, AN Crigler and M MacKuen (eds), The affect effect: dynamics of emotions in political thinking and behaviour, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, 205–206. 14 Bodenhausen, cited in ibid, 208. 15 United Nations,The United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, A/RES/60/288, 20 September 2006, http://daccess-dds-ny. un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N05/504/88/PDF/ N0550488.pdf?OpenElement. 16 MP Arena and BA Arrigo, The terrorist identity: explaining the terrorist threat, New York: New York University Press, 2006, 27–28. 17Z Abádi-Nagy, Theorizing collective identity: presentations of virtual and actual collectives in contemporary American fiction, Neohelicon 30(1) (2003), 176. 18 B Simon and B Klandermans, Politicized collective identity: a social psychological analysis, American Psychologist 56(4) (April 2001), 321. 19 G Almond and S Verba, The civic culture, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963, 380–381. 20 K Deininger, Causes and consequences of civil strife: micro-level evidence from Uganda, Oxford Economic Papers 55(4) (2003), 599. 21 C Tushambomwe-Kazooba, Causes of small business failure in Uganda: a case study from Bushenyi and Mbarara towns, African Studies Quarterly 8(4) (2006), 27–35. SA Peterson and A Somit, Cognitive development and childhood political socialisation, American Behavioral Scientist 25(3) (January/February 1982), 324. 22 Dawson and Prewitt, Political socialization, RE Dawson and K Prewitt, Political socialization, Boston: Little, Brown, 1969, 50. 23 The Transitional National Government was 7 J Duckitt and CH Sibley, Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: a dual-process motivational model, Journal of Personality 78(6) (December 2010), 1869. 8 RS Sigel and MB Hoskin, Perspectives on adult political socialisation – areas of research, in SA Renshon (ed.), Handbook of political socialisation, New York: Free Press, 1977, 265. 9 TR Gurr, Terrorism in democracies: its social and political bases, in W Reich (ed.), Origins of terrorism: psychologies, ideologies, theologies, states of mind, Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1990, 87. 10 E Quintelier, D Stolle and A Harell, Politics in peer groups: exploring the causal relationship between network diversity and political participation, Political Research Quarterly 20(10) (2011), 2. 18 11 M Cottam, B Dietz-Uhler, EM Mastors and T 129–130. established in April–May 2000, but had little power. Following the ‘merging’ of moderate leaders, the Transitional Federal Government of the Republic of Somalia (TFG) was established in November 2004. Despite growing support for the Islamic Courts Union (the forerunner to al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam) until its defeat in 2006, the TFG was the internationally recognised government until the Federal Government of Somalia was inaugurated on 21 August 2012. Its authority is growing, but al-Shabaab still controls large parts of the country. 24 IL Janis, Group identification under conditions of external danger, in D Cartwright and A Zander (eds), Group dynamics: research and theory, New York: Harper & Row, 1968, 80. 25 CR Mitchell, The structure of international conflict, London: Macmillan, 1989, 88. Radicalisation and al-Shabaab recruitment in Somalia 26 JM Post, ’It’s us against them’: the group dynamics of political terrorism, Terrorism, 10 (1987), 24. 27 DM Taylor and W Louis, Terrorism and the quest for identity, in FM Moghaddam and AJ Marsella (eds), Understanding terrorism: psychological roots, consequences and interventions, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2004, 172–173. 28 Abádi-Nagy, Theorizing collective identity, 177. PAPER About the authors ISS Pretoria Anneli Botha has been a senior researcher at the ISS in Pretoria since 2003. After completing an honours degree in international politics she joined the South African Police Service’s Crime Intelligence Unit in 1993, focusing, among other things, on terrorism and religious extremism. She has a master’s degree in political studies from the University of Johannesburg and a PhD from the University of the Free State. Her specific areas of interest are counter-terrorism strategies and the underlying causes of terrorism and radicalisation. Block C, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346 9500 Fax: +27 12 460 0998 pretoria@issafrica.org Mahdi Abdile is the FCA Deputy Regional Representative for East and Southern African Regional Office. He is currently completing his PhD thesis in the Department of Political and Economic Studies at the University of Helsinki, Finland. He has participated in several EU and Academy of Finland research 5th Floor, Get House Building, Africa Avenue Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tel: +251 11 515 6320 Fax: +251 11 515 6449 addisababa@issafrica.org projects on diaspora involvement in peacebuilding in the Horn of Africa. For the past five years he has worked for a number of international organisations and as a consultant for the United Nations. About the ISS The Institute for Security Studies is an African organisation that aims to enhance human security on the continent. It does independent and authoritative research, provides expert policy analysis and advice, and delivers practical training and technical assistance. About Finn Church Aid Finn Church Aid (FCA) is the largest NGO in Finland working in development cooperation, and second-largest in humanitarian assistance. FCA implements programmes in 30 countries and provides assistance when and where it is most needed, irrespective of religious beliefs, ethnic background or political convictions. FCA works towards a world with justice and human dignity for all. Acknowledgements This study was funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland and is the result of a partnership between Finn Church Aid and the ISS. The study was commissioned by the Network of Religious Leaders Peacemakers, the ISS and Finn Church Aid. FCA is a partner organisation of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The ISS is grateful for support from the members of the ISS Partnership Forum: the governments of Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United States. ISS Addis Ababa ISS Dakar 4th Floor, Immeuble Atryum Route de Ouakam Dakar, Senegal Tel: +221 33 860 3304/42 Fax: +221 33 860 3343 dakar@issafrica.org ISS Nairobi Braeside Gardens off Muthangari Road Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 266 7208 Fax: +254 20 266 7198 nairobi@issafrica.org www.issafrica.org ISS Paper © 2014, Institute for Security Studies and Finn Church Aid Copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Institute for Security Studies, and no part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express permission, in writing, of both the authors and the publishers. The opinions expressed do not reflect those of the ISS, its trustees, members of the Advisory Council or donors. Authors contribute to ISS publications in their personal capacity. No 266