the battle of orleans, 1814 - Orleans Historical Society

THE BATTLE OF ORLEANS, 1814

By Admont G. Clark

For the Orleans Historical Society

Based on The Battle of Orleans, Massachusetts (1814) and Associated Events

By Richard K. Murdoch

As printed in The American Neptune, A Quarterly Journal of American History, July 1964

The short battle between British marines and Orleans and Brewster militia on 19 December

1814, has been called “the Battle of Orleans”. The British intended to bomb boats, destroy salt works, and bomb the town. A number of histories report the event; most notably perhaps Henry C.

Kittredge’s Cape Cod; It’s People and Their History (Boston, 1930). Even newspapers of the time are quite unreliable due to the fact that there were no reporters on the scene at the time. They had to base their reports on local accounts or copy their information from other papers.

But there was another source — the logs of the British ships involved. The difficulty with ship’s logs is that the captain, due in large part to the stress of events, usually puts down just the bare bones of an event. However, the logs from H.M.S. Newcastle are verified by those of H.M.S. Acasta and H.M.S. Arab , both involved in the blockade of Boston.

The Newcastle grounded off the tip of Billingsgate Shoal in the darkness of 12 December

1814. The next day the Newcastle crew threw overboard a mast and spars to try to lighten the ship.

Many of these items were salvaged by Orleans residents who made a raft of them and towed it to

Rock Harbor Creek. They also chopped up much of the debris to render it useless to any British salvage crews.

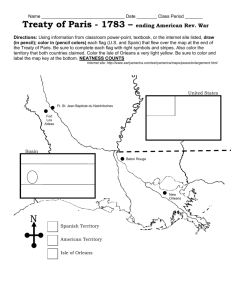

On 13 December, Captain Lord George Stuart of the Newcastle sent a launch and a yawl to recover the scuttled gear. They encountered an American sloop from Boston sent with provisions, which had grounded at the mouth of Rock Harbor Creek. Much of its crew escaped, but the British seized the sloop’s cargo and one remaining American. Sailing north in the dark towards the

Newcastle , which was at anchor off Truro, the yawl grounded off Wellfleet Harbor. Many of the crew abandoned the vessel.

The arrival on the 16th of the H.M.S. Acasta , one of the ships assisting in the blockade of

Cape Cod Bay, allowed Captain Stuart to do a reconnaissance of the Orleans shore. He had been informed that the townspeople had claimed the lost gear, and that a number of American fishing vessels were in Rock Harbor Creek. Early on 19 December, he dispatched four armed barges to reclaim his gear.

One barge, under Lieutenant Frederick Marryat with 22 men and marines, led the way to the mouth of Rock Harbor Creek. Entering the creek, Lt. Marryat ordered the other barges to blockade behind him. There he saw the sloops Camel , Washington , and Nancy before him, as well as the schooner Betsy , heavily loaded with salt.

All four unmanned vessels were taken. Men at work nearby at the saltworks alerted the town.

Once again, one American was captured and under falling darkness was made to pilot the Betsy toward where the Newcastle was anchored. The imprisoned pilot managed to ground the vessel to the west on Yarmouth Beach. Both vessel and crew were taken by Yarmouth militia who had been alerted of events in Orleans.

Meanwhile, after surveying the damaged gear in the creek, Lt. Marryat began to follow his orders to take revenge on the town of Orleans for destroying British property by setting fire to the sloops and the pier and burning the saltworks, dumping the salt into the water. (Having been invented

on Cape Cod at the beginning of the 19th century, saltworks had become an extremely viable industry for coastal towns, and thus a likely target for British revenge.) As this was going on, musket shots rang out from the cover of nearby trees, fatally wounding one marine and hitting several others.

The British returned fire, but no one was hit. There is no evidence to cover the claim that “there was a pitched battle in these very streets of Orleans, resulting in the death of several of the enemy.” There was also no naval bombardment of the town since all the ships involved were far from the scene.

Lt. Marryat’s plans of revenge were interrupted before causing too much damage by a large group of armed militia who lay down heavy fire. It is believed that Brewster and Eastham militia had joined the Orleans militia at this point. Because of this opposition, Lt. Marryat ordered his marines to retreat to the barges and sent a crew onto the Camel to sail for Wellfleet. He left the creek on a barge and headed north. Thus ended what is generally referred to as the “Battle of Orleans”.

According to Captain Stuart, who had lost eleven men, “those wretches in Orleans” had reneged on a promise not to fight if the British left the village alone. Official militia records show that Captains Moses Higgins and Henry Knowles called out and paid their companies of one hundred men serving on 19 December 1814.

The night of 19 December produced a heavy snowstorm, grounding Lt. Marryat’s barge.

Accordingly, he transferred the crew and marines to the Camel , standing by in deeper water. By the afternoon of 21 December, having reached the vicinity of the Newcastle , Lt. Marryat was forced to beach the Camel to prevent its sinking and transfer to a longboat dispatched from the Newcastle .

About noon on 21 December, the Arab anchored near the Newcastle and the Acasta arrived from Provincetown. The Arab was sent to scout the bay and reported that the U.S.S. Constitution had gone to sea, perhaps making for the English Channel or the Mediterranean. Since his orders from

Admiral Cochrane were to prevent this very thing from happening, Captain Stuart had to abandon any plans of attacking Orleans and to complete the overhaul of damaged rigging to prepare the

Newcastle and Acasta for sea duty. The night of 22 December was devoted to loading supplies and transferring American prisoners. Captain Jane of the Arab was ordered to meet the British fleet off

Long Island and then proceed to Halifax to deliver the prisoners. The Newcastle and Acasta were ordered to up-anchor on the morning of 23 December and pursue the Constitution in spite of her 6day lead. They would not catch up with her until 12 March 1815 where they would narrowly avoid a battle in the Azores.

The “Battle of Orleans” can’t be considered of great importance in the War of 1812, and in no way does it denigrate the bravery of the people refusing to pay tribute to the enemy and their willingness to attack the British marines. History should remember that Orleans, along with

Barnstable and Falmouth, were the only Cape Cod towns to resist the antiwar stand of Governor

Caleb Swift.

The most important thing about the grounding of the Newcastle on 12 December 1814 and the necessary repairs to the ship lasting ten days was the escape of the Constitution . Having returned to New York 1 May 1815, she found that the war was over. This distraction was fortunate for

Captain Stuart as he might have been questioned by his superiors regarding his many mistakes in

Cape Cod Bay.

Orleans was finally honored when Congress, on 3 March 1855, authorized a bounty of sixty acres of public lands for the survivors of the “Battle of Orleans” and to their surviving widows and children. Though centuries have passed, the harsh words spoken in Congress by the adherents of

Governor Caleb Strong and his anti-war supporters, the fact is that there was a “Battle of Orleans” and the fame of the militias still stands for their courage and patriotism.