REALITY AND CREATIVITY

advertisement

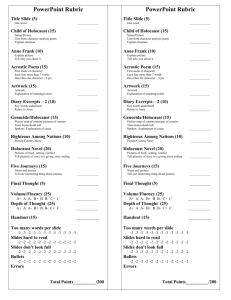

Pauline Hurley Post Graduate Certificate in Holocaust Education. REALITY AND CREATIVITY The search for Post-Holocaust identity through the use of memory and new language creation in the works of poet Paul Celan, artist Judy Chicago and musician Steve Reich. “The task of memory is to fight the risk that history will finally fall into the dark side of lethe.” Note: I envisage the following dissertation as being useful to teachers of senior cycle who have an interest in developing new routes into Holocaust education and who wish to explore the creation of a new module for their classroom. The content is suitable for students with a good prior knowledge of the Holocaust. The development of the material by teachers calls for a cross-curricular approach which supports the use of ‗Multiple Intelligences‘ and ‗Assessment for Learning‘ techniques. The choice of content is subjective to this writer but there is adequate scope for teachers to develop their own choices which are very much dependant on specific student requirements. Self-directed learning and a willingness to explore Post-Holocaust memory, identity and language are facets that are paramount to student engagement with the material. To speak of the creation of memory through new language in Post-Holocaust terms is perhaps somewhat contradictory. After all, the erasure of memory seemed to have been a necessity for the continuation and renewal of a normality of sorts. Memory loss and negation of identity seem to be, on the surface at least, less problematic than the self-reflective analysis and genesis of memory that this writer will focus on. The three varying genres of poetry, art and music allow for an exploration of the reality of the experience of Celan paralleled with a possible identification with the creative process and questioning of the final artistic products of Reich but particularly Chicago. All three, I believe, show the difficulty of searching for a Post-Holocaust identity which allows for a questioning of the role of artistic endeavour and the acceptance of a limited language in an environment where some think that the ―Holocaust cannot be explained or visualised‖.1 This essay will begin by looking at the work of survivor Paul Celan who expresses the inexpressible and compare this with Chicago and Reich, both of whom are influenced by personal experience, their Jewish heritage and their search for identity. ―Through the sluice I had to go, to salvage the word back into and out of and across the salt flood‖ The Sluice Paul Celan(was born Paul Antschel) in Czernowitz, Bukovina. His parents were German speaking Jews and he lived in a multi-ethnic environment alongside ―Romanians, Ukrainians, Germans, Poles, Hutzuls and Gypsies‖ 2 Celan wrote poetry from an early age and began to find recognition at the time when Adorno stated that ―to write poetry after Auschwitz was barbaric‖3 Celan‘s voice in his poetry comes to us through German, which his mother in particular wished him to speak. High German was after all the language of the cultured and educated. His German mother 1 Elie Wiesel Felstiner, J, Paul Celan, Poet, Survivor, Jew,( Yale University, 2001), introduction pg xvii 3 Adorno revised this statement in 1973 in response to Celan‘s work 2 tongue became ―memory-rich and memory-ridden.‖4 He wrote about 800 poems between 1938 until his death in 1970. Most of these poems center on his search for identity and his creation of a new way of describing the indescribable. Many have questioned his inaccessibility, including those who rejected him for the Nobel prize in 1966. Yet Celan himself stated that ―I went with my very being towards language‖ and according to Felstner that is ―what the reader is apt to do in order to meet him half way.‖5 His identity and his language were very much bound together and when this identity was broken so was his connection with the language he knew. All of Celan‘s poetry must therefore be approached through his ―speech-grille‖ and translated back and through this new language. The development of his new identity does of course have its genesis in the actuality and memory of the Holocaust. There is some obscurity about the facts relating to the deportation of Celan‘s parents. Celan never spoke publicly about the event and the details seem somewhat vague. Fellow survivor Alfred Kittner felt that ―he suffered a severe psychic shock he never overcame and felt a heavy burden of conscience- the thought that maybe he could have prevented his parents‘ murder in the camp if he had gone with them‖6 An East German émigré poet published an account supposedly given to him by Celan of a camp selection where Celan slipped from one line to another thus allowing someone else take his place in the gas chambers. This then gave Celan‘s writing a ―futile attempt to silence the voice of guilt‖.7 Celan‘s friend Ruth Lacher gives an account of finding a small office in a factory and telling Celan to hide there with his parents during the roundups. Celan did in fact hide there but without his parents who apparently refused to go. On returning home after one such roundup Celan found his home sealed and his parents gone. His father died from typhus and his mother was shot as ‗unproductive‘. This loss obviously permeates his poetry. His own period of forced labour from 1942-1944 also remains obscure. When asked what he did during this time he replied ―shovelling‖ 4 Chalfen, I Paul Celan, A Biography Of His Youth,( N.Y. 1979), pg xx of introduction Felstiner, Paul Celan, pg 20 6 Ibid, pg 26 7 This account is problematic as it would suggest that it was easy to slip from one line to another at selection and we do not have any corroborating evidence for this 5 and did not go into further details. This is undoubtedly understandable and indeed the word shovelling brings to mind a multitude of images all equally horrific. On hearing of his father‘s death he wrote‖ Black Flakes‖(see appendix 1). He recreates a memory in the poem of receiving a letter from his mother telling him of the death of his father. We hear the son‘s voice in the first stanza, the mother‘s next and then the son‘s again. ‗Black Flakes frames memory around experience‖ 8. It also centres on his Jewishness as it remembers Jacob- the song of Cedar. Also this reference points to the Biblical cedars of Lebanon and the anthem of the first Zionist congress ―There where the slender cedar kissed the skies/ …there on the blue sea‘s shore my homeland lies. Here we see a link to Celan‘s father and his Zionist leanings which at this time Celan did not follow. The snow falls at the start of the poem and reminds us of the 16th century folk song ―The snow has fallen‖. Here ―the lover begs his beloved to wrap him in her arms and banish winter‖9 Winter though is not banished. The Christian hope seen in the ―monkish cowl‖ also refuses to bring hope. The only minute hope is found through his mother‘s letter but this again is paradoxical as the letter tells of the death of his father. He makes her letter part of the poem and in a sense she becomes his muse. Her, and in a sense, Jewish persecution is seen from Jacob through to the 17th century Hetman to the present Second World War. ―Black Flakes holds in a single moment the European Jewish catastrophe, Paul Antschel‘s private loss and a poet‘s calling.‖ 10It is especially poignant as we see the role reversal of the mother-child relationship. Here it is the mother figure who seeks help from the child. This is an all too common image in Holocaust history. In late 1942 or early 1943 Celan found out from a relative who escaped Transnistria that his mother had been shot as unproductive, in other words, unable to work and therefore a ‗useless eater‘. On hearing this he recreated a scene from a memory made from this information and created ―Winter‖ (see appendix 2). Here he specifically mentions a place, the Ukraine, thus making the memory real and tangible. The ―Saviour‘s Crown‖ again brings no solace and the ‗victims‘ arms are ―candlesticks‖ 8 Felstiner, Paul Celan, pg 19 ibid 10 Ibid, pg 21 9 reminiscent of menorah. Celan seems to set Christian suffering against Jewish suffering. The image of the harp has associations with exile.11 The poem ends with a question to his mother. Would the poet in him awaken if he too sank in the snows of the Ukraine? Again the poignancy and loss are evident here as is his link with Jewish imagery and his search for his identity without his parents, particularly his mother. ‗Aspen Tree‘(see appendix 3) also locates his loss in the Ukraine where ―my yellowhaired mother did not come home‖ and ―my gentle mother cannot return‖. The possessive ‗my‘ reverberates throughout this poem and makes the loss seem greater to Celan yet from a survivor‘s point of view it could be any mother dying at anytime during the Holocaust. When Celan returned from forced labour camps he had created 93 poems. He then began working in a psychiatric clinic and also translated texts from Romanian to Ukrainian. He began studying English at what was then a Soviet sponsored university. He felt though that there was nothing for him in what was Bukovina and he did not want to live under a Soviet regime. It was about mid 1944 that news of the death of his uncle, Bruno Schrager, who had lived in Paris, reached him. He had been deported from Drancy to Auschwitz. From his transport of 500 only 30 survived. It was also at this time that further details of the death camps were being spoken about and this led Celan to write what is deemed to be his most famous poem Todesfuge (translated Deathfuge, Fugue of Death, Death‘s Fugue or Death Fugue). (see appendix 4 and ,www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVwlqEHDCQE) ―No lyric has exposed the exigencies of its time so radically as this one, whose speakers- Jewish prisoners tyrannized by a camp commander- starts off with the words Black milk of day-break we drink it at evening‖12 The metaphors for the reader of black milk, graves dug in the air, hair of ash, dances fiddled for gravediggers are not metaphors for survivors but reality. Celan here is memory keeper and reporter. The fact that Celan had begun the poem in late 1944 (but later dates it to 1945) shows the immediacy of the memory and the new identity created by those who had to live such ‗metaphors‘. The need for the creation of new language to describe what had not 11 12 Psalm 137- ―We wept when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows‖ Felstiner, pg 26 previously been even imagined is evident. This new language is made of ―ruptured syntax, ellipses, buried allusion and contradiction,‖13 plus repetition and images that are not created from poetic imagination but are grounded in reality. The connection of music with death during the Holocaust is extremely poignant. Near Czernowitz at the Janowsk camp in Lvov an SS lieutenant ordered Jewish fiddlers to play a tango with new lyrics called death tango. This was used during marches, tortures, grave digging and executions. Celan originally called his poem death tango. At Auschwitz the orchestra played tangos and prisoners used the term death tango for what ever music was being played when prisoners were shot (see appendix 5). Celan did associate death and music. Bach fugues were heard from the commandant‘s house in Auschwitz and Primo Levi says it is the last thing that could be forgotten from the lager. ―In this poem we find traces of Genesis, Bach, Wagner, Heinrich Heine, the tango, Faust‘s heroine Margareta alongside Shulamith from the Song of Songs.‖ 14 As well as showing Celan‘s own suffering ―we shovel‖ it also shows the suffering of others in the camps. On listening to Celan‘s recording of Todesfugue one is immediately struck by the urgency, rhythm and rhyme of the poem even if one is unable to understand the language. The musicality of the poem is very obvious and this connection between death and music becomes embedded in the narrative of the work. All four stanzas start with ―black milk‖. This image of the food of milk being relegated to something unpalatable yet consistently evident in the camps goes against the nurturing image of milk. Some have questioned the need for figurative language to describe the living death of the camps but I feel that Celan creates for those of us who cannot begin to imagine the horrors of camp life, an image that goes beyond poetics into the realm of reality. Celan makes the commandant write home to his loved one, his ―golden haired Margareta‖. She is epitome of the eternal feminine. This same man who is able to write love letters is able to whistle his hounds to come close and his Jews to appear. We are told through a victim‘s voice that he also orders them to ―play up for the dance‖ giving the reader an image of death. The black milk has now become ‗you‘ instead of ‗it‘. The ‗ashen haired Shulamith‘ is summoned into the poem. Her name has overtones of ‗shalom‘ and ‗Yerushalayim – Jeruslaem‘. She is 13 14 Ibid, pg xv11 Felstiner,Paul Celan, pg 26 therefore a sign of hopefulness particularly when we realise that she promises a return to Zion in the ‗Song of Songs‘. Yet Celan does not allow a connection between Margareta and Shulamith and thus there is no return for the majority. However Shulamith ends the poem holding on to an identity. She has the last word. Perhaps we can see here a glimpse of hope for the future but she also holds the memories of those who have died and the anguish created by their loss. By the end of 1945 Celan left for Bucharest ―crossing a personal as well as political border‖.15 A Song in the Desert came from the period 16 (see appendix 6). As well as seeing himself as a wanderer he also changes his name to Celan. This change of name must have had an emotional impact and again led to a search for new identity. By 1947 Jews were reaching Vienna, their spiritual home. Celan was amongst them. By 1948 the Austrian government had ‗forgiven‘ all minor offenders in the Holocaust and Celan stated that ―I did not stay long, I found nothing I‘d hoped to find‖. 1948 was also a period for Celan that he found difficulty in writing ―for months I haven‘t written because something unnameable is laming me‖. His subsequent move to Paris produced Number me among the almonds (see appendix 7). The poet here is speaking to his mother and the image of the almond represents his Jewishness. 17 The order to count also has connotations around the Nazi headcount in the camps. Supposedly the gas Zyklon B also had a smell of almonds. 18 The idea of remembering and naming restores the identity of those who were murdered and dehumanized. This of course included the poet himself who is still on a journey seeking his identity. The latter was also under duress during his trip to Germany in 1952 where he stated that he felt used within Germany‘s cultural recovery after the third Reich. His poem Todesfugue had found itself onto the German school curriculum and both teachers and students alike were in awe of it. They did though seem to respect it more for its technical brilliance rather than for its content. Students seemed to view it as a positive step towards forgiveness and reconciliation rather than a mouthpiece for those who were murdered. 15 Felstiner, Paul Celan, pg 43 A song in the wilderness telling of the Israelites exodus from Egypt 17 Num 17.23 Aaron‘s rod bears ripe almonds Exod. 25.33 The Israelites menorah in the wilderness has almond blossom designs 16 18 Felstiner, Paul Celan, pg 64 This, along with other misrepresentations of the poem, seemed to make Celan lose faith in it and even when in Israel he did not recite it. Celan seems by the mid 1950s to have incorporated his Jewish tradition into the essence of his identity and has done this through memory and language. The Hebrew ―Shibboleth‖ serves the purpose of counting him amongst those who knew the password for suffering (see appendix 8). His cry of shibboleth in an alien world searches for those like him and again links his poetry to his tradition. 19 He also makes reference to other historical events like the destruction of Austrian socialism and Spanish republicanism. He links events in this poem to the month of February thus following the ―ancient Jewish bent of mind‖, 20 marking great historical events on a single date. This poem was included in a book of poetry called ‗From Threshold to Threshold‘ suggesting that Celan reaches a threshold but cannot enter and then moves on to another. Celan said ―I am on the outside‖ and this feeling sums up his longing to belong. This longing began to lead to bitterness for Celan. This is very evident in Tenerbrae from 1957 (see appendix 9) where Celan seems to be enveloped in an emotional darkness and his references bear this out.21 The connection between Catholic and Judaic mysteries is obvious here yet there is no saving grace. The ‗clawed and clawing‘ are almost animalistic images and in the film ‗Night and Fog‘ we are reminded about the clawing inside the gas chambers.22 The terrain in the poem is open and wild and evokes the terrain of the Einsatzkommandos. Celan tries to reclaim the fate of the Jews by showing their image in Christ‘s reflection. He reclaims suffering from the Christian tradition to that of the Jewish but again there doesn‘t seem to be any hope of salvation. In 1958 he won the Bremen prize for literature and based his speech on ‗thinking and thanking‘. He also spoke about his origin ―it was a region in which human beings and books used to live‖. Without saying too much he says a lot and allows the audience to 19 Shibboleth is an Israelite tribal password that the Gileadites used at the river Jordan against the Ephraimites. Mispronunciation of this word led to death and identified friend from foe. 20 Felstiner, Paul Celan, pg 82 21 Gen 1:2 darkness upon the face of the deep Exodus 10:22 darkness in all Egypt Deut 5:20 God speak out amid darkness at Sinai 22 Night and fog at 4 min 94 recognise that his poetry has to use language that ―gave back no words for that which happened‖. He therefore had to create new words and new ways of speaking in a tongue which was a constant reminder of death. It is unsurprising really even at this stage that Celan did not speak out against Nazi genocide in a more direct way but again allowed his poetry to reach out like ―a message in a bottle…in the belief that somewhere and sometime it could wash up on land, on heartland perhaps‖23 In 1958 he also recorded Todesfugue. This was its only recording. 1959 saw the birth of There was earth inside them (see appendix 10.) where those in the camps or those now as survivors dig and dig and do not praise God. 24 They are in fact digging their own graves. Celan may also have been reminded of Jacob Glatstein‘s poem ―We received the Torah in Sinai And in Lublin we gave it back Dead men don‘t praise God‖25 The Dead don‘t praise God Those digging did not learn a new song so now it is up to Celan to learn this song, this new way of speaking, this new language. Nineteen sixty saw the media reporting on Nazi criminals as well as new neo-Nazi tendencies. Celan was also falsely accused of plagiarism, a charge which he never fully forgot. Psalm (see appendix 11) was written at this time and his poetry in general resonates with Jewish themes and imagery. He states that he is trying to hold onto what is left of him and his poem Psalm reflects this in a prayer-like way. In 1962 he wrote no poetry as he now suffered from depression from which he felt enveloped. His doctors told him that this depression could not possibly be linked to events of the Holocaust as these events were too far removed from him now. It was perhaps in some way to receive an acknowledgement of his and others suffering that he visited the philosopher Martin Heidegger whom he admired but had declared the ―inner truth and greatness of Nazism‖ in 1935. His poem Todtnauberg (see appendix 12) speaks of 23 Felstiner, Paul Celan, pg 115 Psalm 115:16 ―and the dead praise not the Lord, neither they that go down into silence‖ 25 Felstiner, Paul Celan, l pg151 24 this meeting. The naming of Arnica at the start should signify healing but this does not follow through in the poem. ―along the paths of German language Celan could only go half way with Heidegger‖.26 A word of acknowledgement or sorrow did not come from the latter. On Celan‘s trip to Israel he stressed his Jewishness and also the fact that the German culture was also important to him. He seems to revel in uniqueness of this visit and said that ―Jerusalem would be a turning, a caesura in my life‖. That positive turning point was not to be as Celan committed suicide by drowning around Passover, April 1970. Fault feels that maybe he felt too alone as ―no one witnesses for the witness‖. Language in Celan‘s poetry is a reminder though of individuality and a return to humanization of Holocaust ‗victims‘. ―The German language for him was never far removed from the lacerations of pain and death held in memory.‖ 27 He searched for words that had not been replicated in history and this search led him to examine memory, albeit in a difficult way, and to create a new identity, one which allowed him to speak in a language of ―shibboleth‖ and be understood by those dispossessed by language and those willing to open his message in a bottle with his ‗variable key‘. Unlike Celan, Judy Chicago‘s Holocaust journey began through a chance meeting with the poet Harvey Mudd in Sante Fe, 1984. Mudd had just completed a long poem on the Holocaust and spoke to Chicago about this. To his amazement she knew very little about the Holocaust and had never heard of the words ‗Arbeit macht frei‘. So began her interest and her search for her own Jewish identity and heritage as well as several years of research which would ultimately result in ‗The Holocaust Project, From Darkness Into Light‘. Her prior work had received as much criticism as acclamation. The ‗Dinner Party‘ in particular, which according to Chicago is a ‗symbolic history of women in Western Civilization‘, has been the subject of much debate and discussion. As a pioneer of feminist art and founder of the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s, her work spans topics such as pregnancy, childbirth and menstruation. How then does Chicago deal with the topic of the Holocaust and how does she claim to represent the suffering of Holocaust ‗victims‘ through her art? Does 26 27 Ibid, pg 246 Wordtraces, Readings of Paul Celan, ed Aris Fioretos,( London, 1994), pg 113 Chicago, through creativity and imagination, link in anyway to the raw emotion of Celan who had first hand experience? Her own heritage and her search for identity as well as her creation of new means of communication through art all combine to shed some light on these questions. Like Celan, Chicago changes her surname. The magazine ‗Artform‘ says that she did so ―to divest herself of all names imposed on her through male social dominance‖. For both then, albeit for different reasons, there is a liberation attached to a change of name as well as the genesis of a new identity. For Chicago, this is very much bound up with what she sees as power and powerlessness. Her feminist leanings see her equating all power as being divested in a male dominated society from which females, particularly female artists, have been written out of. From this idea she began to focus on the construction of masculinity and its relationship to power and this along with her fledgling interest in the Holocaust led her to her Holocaust Project. Growing up in a very politically aware household, of Jewish parents and a father in particular who encouraged his daughter to debate and question everything, it is for Chicago, almost unbelievable that the Holocaust was barely mentioned. Neither of her parents ―liked the politics of the Jewish organisations, as for Zionism, my father had dismissed Israel as a potential power keg.‖ 28 This aside, it is still ironic that such a major part of Jewish history was not discussed in what was an era for her of questioning. Chicago‘s mother recounts the story of listening to a Rabbi answer a question about the Holocaust during the early 1940s and he ―put his finger to his lips and said, we must say nothing or it will happen to us too‖29 We have no corroborating evidence for this memory but Chicago questioned her mother at length about why she knew so little of the Holocaust. Indeed Chicago states that ―the issue of anti-Semitism was never discussed, not in class, not at home but when a teacher made a comment about Roosevelt and the Jewish conspiracy 95% of the class (who were Jewish) 28 Chicago, J, Holocaust Project From Darkness Into Light, with photographs by Donald Woodman,(N.Y. 1993), pg 24 29 Ibid, pg 29 walked out‖30 Chicago did not analyse this at the time or did she feel that she was being in anyway victimised. It is from this background that Chicago goes on her personal journey to research the Holocaust with her husband the photographer Donald Woodman and they go on to create a new method of combining painting and photography as well as work in stained glass and tapestry, which they envisaged as ―a vehicle for intellectual transformation and social change.‖ 31 Chicago‘s project took her and Woodman through 8 years of travel, study and artistic creation. Both travelled to various Holocaust sites and read widely on the subject. During her travels Chicago kept a diary account of her reactions to various places where her documentation of various sites and events is illuminating for the reader. This is particularly true in Vilna where she said she is descended from Gaon of Vilna, the 18th century Lithuanian Rabbi. Her father had rejected his Orthodox Jewish life and Chicago herself felt that when she visited Israel her feminist ideals were challenged by such Orthodoxy. She then needed to find a way to align her ideas of abuse of power, her feminist values and her tradition into one project while still remaining faithful to the essence of Holocaust representation and memory. Many of the pieces in the Holocaust project take on iconic photographs thus assuring the viewer of its authenticity and its link with primary source material. These photographs are then assimilated into the painting allowing Chicago to incorporate her own memories created from research with the memories of those who had first hand experience of these horrors. ―The Holocaust is approached as an event that happened at the core of our civilization, the heart of our culture and in the midst of societies resembling our own.‖32Chicago also began to see the Holocaust as being engineered solely by men. She acknowledges that women were involved but the architects of the Holocaust were all men. This brings her to her original thesis of women‘s powerlessness and ―the relationship between traditional concepts of 30 Ibid, pg 24 Ibid, introduction. 32 Women and art- an interview with Judy Chicago, N.Y. 1998. 31 masculinity and Nazi ideology‖. 33 She also began to look at the way the Holocaust was represented in different ways in Western and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s. She particularly saw conflict arising from the lack of commeration of gay ‗victims‘ of the Holocaust. Indeed when she was in Dachau in 1987 she witnesses a protest by gay men regarding their lack of acknowledgement. She incorporates this into her paintings. She had some difficulty, at the start at least, in seeing the uniqueness of the Holocaust in its ―intentionality, planning, scope and implementation.‖ 34 She makes unfounded comparisons between the treatment of women in the Holocaust and the burning or witches but eventually through her work the viewer does see ―a method honouring the uniqueness of the Holocaust…a metaphor for the fact that we are examining connections not suggesting that the Holocaust is exactly like any other historic event‖35 This writer feels that Chicago through her comparisons does not see the Holocaust as unique but as ―the universal exposition of victimization that is part of a hierarchical system of power.‖36 In saying that Chicago has been named as one of the 8 Jewish women who changed the world‖37 through her art. ―We can only hope that Judy Chicago‘s unfortunate tendency to tackle and trivialise great issues has peaked with the Holocaust and that she will in future, occupy herself, with some more productive activity – learning to draw, say.‖ 38 Such vitriolic attacks are not uncommon when one speaks about the work of Chicago. Is there some relevance in the comment regarding the trivialisation of the Holocaust? In order to assess this one needs to look at some of the examples of her work from her Holocaust project. Different coloured triangles mark the entrance to the project (see appendix 13) and these are based on the different coloured triangles worn by those in the camps. Chicago reverses the way the triangles were worn in order to suggest power or resistance. The triangles are surrounded by barbed wire and fire. ―The overall image 33 Chicago, Holocaust project, pg 4 Isaiah Kurperstein, paper to the Holocaust Project commissioned by the Spertus Museum 35 Chicago, Holocaust project, pg 10 36 From Jewish Women‘s Archive 37 Union of Reform Judaism, 1998 38 Boston Globe, September 22nd 1995 34 is intended to commemorate the courage and survival of the Holocaust survivors.‖ 39 This image then does correspond with reality and is historically accurate as regards the triangles and colours. Chicago subverts them in order to suggest survival and a viewer would understand this. Actuality and imaginative creation are in alliance with one another here. The Fall (appendix 14) ―provides a retelling of history in which violent, patriarchal civilization overtakes ancient matriarchal cultures.‖ 40It also questions the rise of industrial technology and represents a search for origins, which of course Chicago is concerned with. The middle section rewords ‗Ventruvian man‘ and links the violence of man with the rise of science and technology. On the right hand side there are representations of the Holocaust with particular reference to the assembly line. The graphic details in this part of the painting are in stark contrast to the method in which Celan describes his experiences. Is there a need for graphic images when the viewer has adequate knowledge to fill in the blanks so to speak? Chicago does state that she paints her ‗victims‘ in ways that show their resistance which she felt other Holocaust painting in the 1980s did not do. Bones of Treblinka and Banality of Evil/Struthof (see appendix 15 and 16) both depict the reality of primary source photography with the creativity of painting. The memorial at Treblinka is manipulated with names added to the stones and the photograph of Struthof if manipulated to show the perpetrators and bystanders in front of those going to the ‗showers‘. Again this new way of combining photography and painting allows for a new artistic language to be created in order to communicate with the viewer. Whether one thinks that this manipulation distracts from the central essence of the work is questionable. Wall Of Indifference (see appendix 17) brings up the very relevant question of bystanders and shows in the background examples of death while those in power do nothing. 39 40 Chicago,Holocaust project, introduction Ibid, pg 88 Banality of Evil/Then and Now(see appendix 18) juxtaposes the domestic scene of the SS officer with this family while a chimney can be seen in the background, with that of an 1980s family relaxing while missiles are being tested. This image as with other in the project show Chicago‘s anxiety for the planet and sees the Holocaust as a springboard where other topics can be addresses. We see this again in See No Evil/Hear No Evil and in Four Questions both of which examine modern day dilemmas such as ―When do the end justify the means?‖ and ―Who controls human destiny?‖ Again we see a move away from purely dealing with the Holocaust to the incorporation of varying and wide questions. This writer, while finding the themes interesting, does not think that the juxtapositioning of these with the Holocaust is particularly relevant or necessary. However such a stance is purely a personal one and it is up to each individual to assess his/her own feelings on the matter. Rainbow Shabbat (see appendix 19) ends the project on a note of hope of healing ―heal those broken souls who have no peace and lead us all from darkness into light‖. There are certainly conflicting interpretations when comparing Chicago‘s work with that of Celans. Apart from the difference in genre ,Celan, in his new language ,created a different narrative to that of Chicago, however both experience an inner journey that forms their own personal narratives and as such the Holocaust affected them both albeit from different perspectives. Both feel that they should be voices for the voiceless and Chicago in particular sees that the Holocaust shows the vulnerability of all human beings ―and by extension, of all species on our fragile planet as well‖ 41 She uses her art form to go from ‗darkness to light‘ in her personal quest for reversal of gender imbalance in history plus her desire to develop her relationship between her Jewishness, her art and her womanhood. ―There‘s just a handful of living composers who can legitimately claim to have altered the direction of musical history and Steve Reich is one of them‖ 42 Born in 41 42 Chicago, Holocaust Project, pg 9 The Guardian (London), April 2004 New York and raised there and in California, Reich studied philosophy at Cornell and received an M.A. in music from Mills College. He also studied African drumming and traditional forms of cantillation of Hebrew Scriptures in New York and Jerusalem. His music has been performed by major orchestras throughout the world. During the war Reich made train journeys between New York and Los Angeles to visit his parents who had separated. Years later he thought about the fact that if he had been a Jew living in Europe at this time he would have been travelling on a very different train and taking a very different journey. Reich was very drawn to ―how we normally use language‖ 43 and to the philosopher Wittgenstein‘s examination of the use of everyday speech. Like Celan, Reich felt that there must be ways of searching for words that have no replication in memory. He also became very interested in oral transmission of history and memory and from this began to search for his own identity. ―As a Jew I‘m a member of an ancient civilization but I don‘t have the faintest idea of what it is I come from‖. It was paradoxically the study of West African and Balinese music that awakened his curiosity about his cultural background. This then led on to the writing of ‗Different Trains‘ (see attached CD). Reich states that ―I felt I had to write ‗Different Trains‘. ―I‘ve been given my assignment, just as everyone has his/her assignment and I want to take care of that because it‘s unique‖44 This uniqueness led Reich to create a new musical language from his own memory and also from the memories of Holocaust survivors. Like Chicago, his use of primary source material, through the voices of the individuals in the music, give it an air of authenticity and reality breaks into the creative process. Reich is aware of the sensitivity of using the Holocaust but what makes the piece work for him is ―that it contains the voices of people recounting what happened to them‖ and Reich is ―simply transcribing their speech melody and composing from that musical starting point. The documentary nature of the piece is essential to what it is.‖45 43 Interview with Anne Teres de Keersmaker – ―Do aesthetic influences matter‖? Interview with Steve Reich by Johathon Cott, N.Y. 1996 45 Interview with Steve Reich ―From New York to Vermont: Conversations with Steve Reich‖Rebecca Y Kim. 44 ‗Different Trains‘ marks the genesis of a new compositional method – a new language – where speech recordings generate the musical material for musical instruments. The New York Times hailed it ―as a work of such astonishing originality that break through seems the only possible description‖. Reich assumes the role of reporter and the music is weaved like a tapestry into and through the voices. The link of music with the subject matter is a known historical fact. Primo Levi speaks about the music in the camps as ―infernal‖ and August Kowalczyk who spent a year and a half at Auschwitz remembers the waltzes and arias from operas. The historian Guido Fackler in his essay ―Music in Auschwitz‖ records the case of the violinist Ota Sattler being forced to play ―A Jew had a wife‖ as his wife and three sons filed past him on the way to the gas chambers. The irony then of listening to Reich and applauding his originality while knowing the connotations of the orchestras in the camps is evident. The piece itself is divided into three movements: America - Before the War Europe - During the War After the War In the first movement Reich‘s former governess Virginia and Lawrence Davis, a Pullman porter reminisce about train travel in the United States. American train sounds are heard in the background. In the second movement three Holocaust survivors, Paul, Rachel and Rachella, speak about their experiences in Europe during the war. They talk about their train trips to concentration camps. These children‘s memories are very poignant. They speak about things that mark time for children such as birthdays and school. The story is linear and the accounts take the listener through German invasions, attempts to hide, being taken away on a train, shaven and tattooed. European train sounds and sirens are heard and have replaced the sounds of American trains. In the third movement the three survivors talk about their years immediately after the war and this mixes with recordings of Virginia and Davis. There is a return to American train sounds in this piece. The line ―but today they‘re all gone‖ allows the listener to question whether the reference is to the Jews, the Nazis or the trains. Reich also has one of the survivors tell the story of a young girl who sang for the Germans in the camps. The very last line is ―and when she stopped singing they always said more, more, and clapped‖. The quartet here continues to play and when it stops the listener is left with the feeling of being complicit if he/she also claps. The 46 samples of speech create a new musical language through their use as the source for the melodies. Reich himself also creates an identity where he sees his heritage and his music as being linked and recreates from memory and research ―the only adequate musical response – one of the few adequate artistic responses in any medium – to the Holocaust‖46 Paul Hillier, artistic director of the Kronos Quartet, who were the first to play this piece, feels indebted to Reich for ―unlocking many rooms full of possibilities‖. The Smith Quartets recording of Different Trains at the time of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau shows for this writer the culmination of these possibilities. (www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZRBfRXJyak) For Celan, Chicago and Reich the journey to creation of Post-Holocaust identity through memory and the formation of new language, is a complex and altering experience. For Celan his first had accounts see him take on the role of survivor and reporter whereas for Chicago and Reich the role of reporter is mixed with that of personal journey towards the reawakening of lost heritage and identity. Both Celan and Reich realise the necessity of oblique references which in fact increase the essence of the events unlike Chicago who assaults the viewer with explicit art and personal memory which is at times for this writer is unnecessary. The reality of events for Celan compared with the emotional and artistic creativity of Chicago and Reich allow individuals to respond on a personal level to the different genres and to envisage a revisiting of loss through memory and a realisation that from this ―some other thing is also set free.‖47 46 47 Richard Taruskin Paul Celan BIBLIOGRAPHY Bekker, H, Paul Celan, studies in his early poetry, N.Y. 2008 Felstiner, J, Paul Celan, Poet, survivor, Jew, Yale University, 1995 Word Traces, Readings of Paul Celan, Fioretos, A, ed. U.S. 1994 Rosenthal, B, Pathways to Paul Celan, A History of Critical Responses as a Chorus of Discordant Voices, (studies in modern German literature, vol 73), N.Y.1995 Poems of From New York to Vermont:Conversations Paul Celan, translated by Michael Hamburger, N.Y.1988 Hillard, D, Poetry as individuality, the discourse of observation in Paul Celan, Bucknell University Press, 2010 Chalfen, I, Paul Celan, A biography of his youth,(translated by Maximilian Bleyleben, U.S.1991 Chicago, J, Holocaust Project, From Darkness Into Light, N.Y.1993 http://www.Steve Reich .com /bio.html Interview with Steve Reich by Anne Teresa de Keersmaker Interview with Steve Reich ―with Steve Reich, by Rebecca Y Kim. McCabe, D, Analysis of Steve Reich Different Trains, Mills College, centre for contemporary music, California http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=ql4JmBwpzlg http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZRBfRXJyak http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=RmjgBQicTRC http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVwlqEHDCQE Appendices Appendix 1 Black flakes Snow has fallen, with no light. A month has gone by now or two, since autumn in its monkish cowl brought tidings my way, a leaf from Ukrainian slopes : ―Remember it‘s wintry here too, for the thousandth time now in the land where the broadest torrent flows : Ya‘akov‘s heavenly blood, blessed by axes… Oh ice of unearthly red – their hetman wades with all his troop into darkening suns… Oh for a cloth, child, to wrap myself when it‘s flashing with helmets, when the rosy floe bursts, when snowdrifts sifts your father‘s bones, hooves crushing the Song of the Cedar… A shawl, just a thin little shawl, so I keep by my side, now you‘re learning to weep, this anguish, this world that will never turn green, my child, for your child‖ ! Autumn bled all away, Mother, snow burned me through : I sought out my heart so it might weep, I found – oh the summer‘s breath it was like you. Then came my tears. I wove the shawl. Appendix 2 Winter It‘s falling, Mother, snow in the Ukraine: The Savior‘s crown a thousand grains of grief. Here all my tears reach out to you in vain. One proud mute glance is all of my relief... We‘re dying now: why won‘t you sleep, you huts? Even this wind slinks round in frightened rags. Are these the ones, freezing in slag-choked rutsWhose arms are candlesticks, whose hearts are flags? I stayed the same in darknesses forlorn: Will days heal softly, will they cut too sharp? Among my stars are drifting now the torn Strings of a strident and discordant harp... On it at times a rose-filled hour is tuned. Expiring: once. Just once, again ... What would come, Mother: wakening or woundIf I too sank in snows of the Ukraine? Appendix 3 Aspen tree Aspen Tree, your leaves glance white into the dark. My mother's hair was never white. Dandelion, so green is the Ukraine. My yellow-haired mother did not come home. Rain cloud, above the well do you hover? My quiet mother weeps for everyone. Round star, you wind the golden loop. My mother's heart was ripped by lead. Oaken door, who lifted you off your hinges? My gentle mother cannot return. Appendix 4 Deathfugue Black milk of daybreak we drink it at evening we drink it at midday and morning we drink it at night we drink and we drink it we shovel a grave in the air where you won‘t lie too cramped A man lives in the house he plays with his vipers he writes he writes when it grows dark to Deutschland your golden hair Margareta he writes it and steps out of doors and the stars are all sparkling he whistles his hounds to stay close he whistles his Jews into rows has them shovel a grave in the ground he commands us play up for the dance Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night we drink you at morning at midday we drink you at evening we drink and we drink A man lives in the house he plays with the vipers he writes he writes when it grows dark to Deutschland your golden hair Margareta your ashen hair Shulamith we shovel a grave in the air where you won‘t lie too cramped He shouts dig this earth deeper you lot there you others sing up and play he grabs for the rod in his belt he swings it his eyes are so blue stick your spades deeper you lot there you others play on for the dancing Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night we drink you at midday and morning we drink you at evening we drink and we drink A man lives in the house your golden Harr Margareta Your aschenes Harr Shulamith he plays with the vipers He shouts play death more sweetly this Death is a master from Deutschland He shouts play scrape your strings darker you‘ll rise then as smoke to the sky you‘ll then have a grave in the clouds where you won‘t lie too cramped Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night we drink you at midday Death is a master aus Deutschland we drink you at evening and morning we drink and we drink this Death is ein Meister aus Deutschland his eye it is blue he shoots you with shot made of lead shots you level and true a man lives in the house your goldeness Harr Margarete he looses his hounds on us grants us a grave in the air he plays with his vipers and daydreams der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete dein aschenes Haar Sulamith Appendix 5 Orchestra playing ―Death Tango‖ in Janowska Road Camp, Lvov Appendix 6 A song in the desert A wreath was wrapped in a dense black foliage in the area of Akra: there, I tore around the black horse and thrust at the death with the sword. I also drank from wooden bowls from the ashes of the fountain Akra and moved forward with precipitated sight of the ruins of the sky. For the angels are dead and blind, was the man in the area of Akra, and there is none that look after me in his sleep went to rest here. Shame smashed was the moon, the flower of the area of Akra: Sun bloom, which imitate the thorns there, his hands with rusty rings. So I have to bend down to kiss me probably last, when they pray in Akra. . . O was bad, the breastplate of the night, the blood seeps through the clips! So I was smiling her brother, the iron cherub of Akra. So I speak the name of yet and still feel the fire on the cheeks. NEIGHT Fever is your body of God's brown: My mouth swinging torches on your cheeks. Was not rocked, they sang the song no sleep. The hand full of snow, I went to you, and uncertain, as your eyes Blauner in Stundenrund. (The moon was once a round.) Verschluchzt in empty camping is the miracle iced the jug dream - what does it matter? Memorial: a blackish sheet hung in the elder the nice sign for the cup of blood. Appendix 7 Number me among the almonds Count up the almonds, count what was bitter and kept you waking, count me in : I looked for your eye when you opened it, no one was looking at you, I spun that secret thread on which the dew you were thinking slid down to the jugs guarded by words that no one‘s heart found their way. Only there did you wholly enter the name that is yours, sure-footed stepped into yourself, freely the hammers swung in the bell frame of your silence, the listened for reached you, what is dead put its arm around you also and the three of you walked through the evening. Make me bitter. Count me among the almonds. Appendix 8 Shibboleth Together with my stones grown big with weeping behind the bars, they dragged me out into the middle of the market, that place where the flag unfurls to which I swore no kind of allegiance. Flute, double flute of night: remember the dark twin redness of Vienna and Madrid. Set your flag at half-mast, memory. At half-mast today and for ever. Heart: here too reveal what you are, here, in the midst of the market. Call the shibboleth, call it out into your alien homeland: February. No pasarán Unicorn: you know about hte stones, you know about hte water, come. I shall lead you away to the voices of Estremadura Appendix 9 Tenerbrae We are near, Lord, near and at hand. Handled already, Lord, clawed and clawing as though the body of each of us were your body, Lord. Pray, Lord, pray to us, we are near. Wind-awry we went there, went there to bend over hollow and ditch. To be watered we went there, Lord. It was blood, it was what you shed, Lord. It gleamed. It cast your image into our eyes, Lord. Our eyes and our mouths are open and empty, Lord. We have drunk, Lord. The blood and the image that was in the blood, Lord. Pray, Lord. We are near. Appendix 10 There was earth inside them There was earth inside them, and they dug. They dug and dug, and so their day Went by for them, their night. And they did not praise God, who, so they heard, wanted all this, who, so they heard, knew all this. They dug and heard nothing more; they did not grow wise, invented no song, thought up for themselves no sort of language. They dug. There came a stillness, and there came a storm, all of the oceans came. I dig, you dig, and the worm, digs too, and the singing there says: They dig. O one, O none, O no one, O you: Where did the way lead when it lead nowhere? O you dig and I dig, and I dig towards you, and on our fingers the ring awakes. Appendix 11 Psalm No one kneads us again out of earth and clay, no one conjures our dust. No one. Praised be your name, no one. For your sake we shall flower. Towards you. A nothing we were, are, shall remain, flowering: the nothing-, the no one‘s-rose. With our pistil soul-bright, with our stamen heaven- ravaged, our corolla red with the crimson word which we sang over, O above the thorn. Appendix 12 Todtnaugerg Arnica, eyebright, the draft from the well with the starred die above it, in the hütte, the line —whose name did the book register before mine—? the line inscribed in that book about a hope, today, of a thinking man‘s coming word in the heart, woodland sward, unleveled, orchid and orchid, single, coarse stuff, later, clear in passing, he who drives us, the man, who listens in, the halftrodden wretched tracks through the high moors, dampness, much. Appendix 13 Coloured Triangles Appendix 14 The Fall Appendix 15 Bones of Treblinka Appendix 16 Banality of Evil/ Struthof Appendix 17 Wall of Indifference Appendix 18 Banality of Evil/ Then and Now Appendix 19 Rainbow Shabbat