4. Love and the Machinery of War - Gutenberg

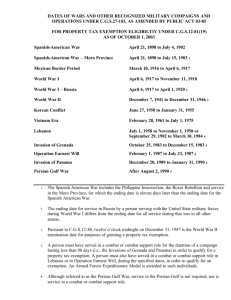

advertisement