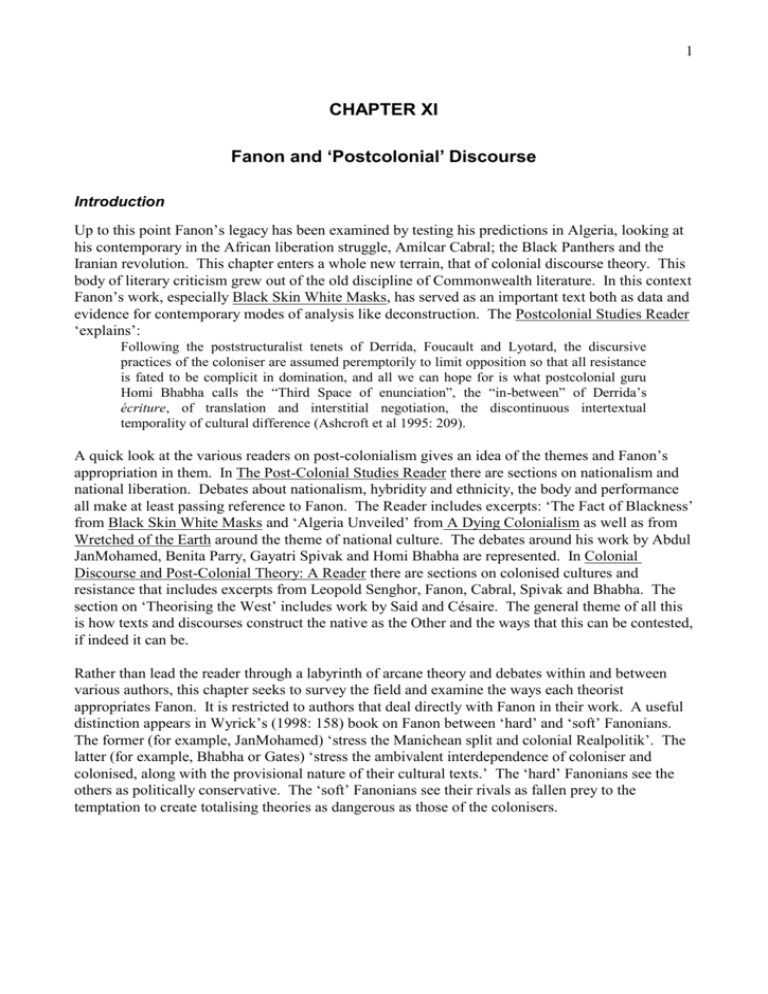

CHAPTER XI Fanon and 'Postcolonial' Discourse

advertisement