LA_TIMES_2009 Click to Open and Read

advertisement

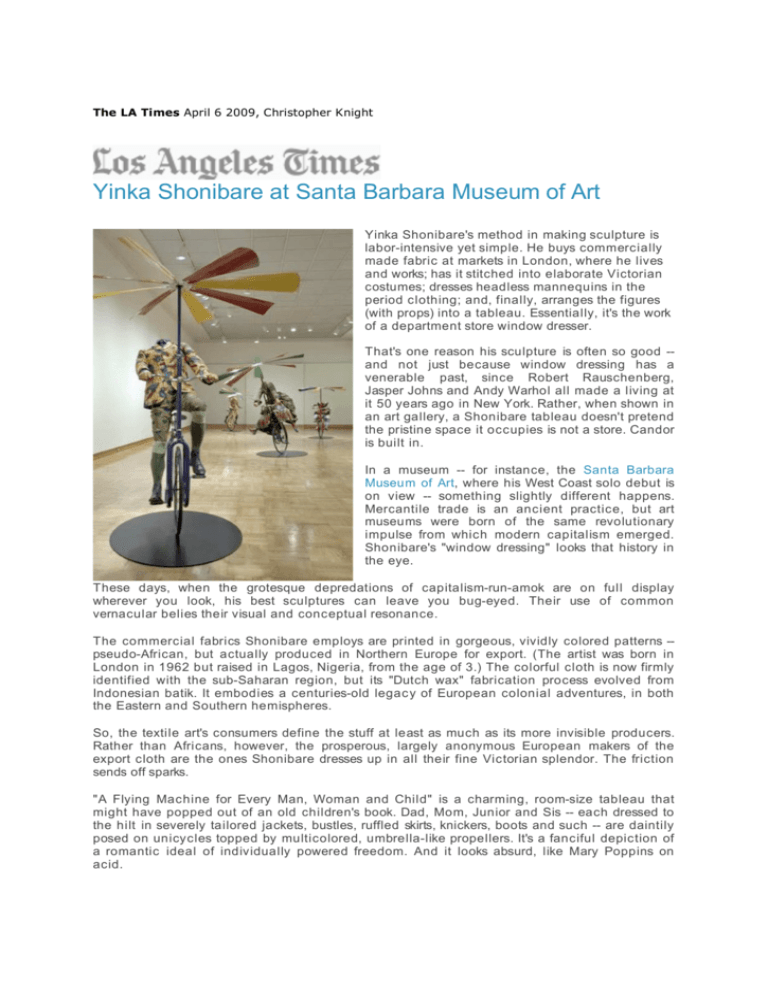

The LA Times April 6 2009, Christopher Knight Yinka Shonibare at Santa Barbara Museum of Art Yinka Shonibare's method in making sculpture is labor-intensive yet simple. He buys commercially made fabric at markets in London, where he lives and works; has it stitched into elaborate Victorian costumes; dresses headless mannequins in the period clothing; and, finally, arranges the figures (with props) into a tableau. Essentially, it's the work of a department store window dresser. That's one reason his sculpture is often so good -and not just because window dressing has a venerable past, since Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol all made a living at it 50 years ago in New York. Rather, when shown in an art gallery, a Shonibare tableau doesn't pretend the pristine space it occupies is not a store. Candor is built in. In a museum -- for instance, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, where his West Coast solo debut is on view -- something slightly different happens. Mercantile trade is an ancient practice, but art museums were born of the same revolutionary impulse from which modern capitalism emerged. Shonibare's "window dressing" looks that history in the eye. These days, when the grotesque depredations of capitalism-run-amok are on full display wherever you look, his best sculptures can leave you bug-eyed. Their use of common vernacular belies their visual and conceptual resonance. The commercial fabrics Shonibare employs are printed in gorgeous, vividly colored patterns -pseudo-African, but actually produced in Northern Europe for export. (The artist was born in London in 1962 but raised in Lagos, Nigeria, from the age of 3.) The colorful cloth is now firmly identified with the sub-Saharan region, but its "Dutch wax" fabrication process evolved from Indonesian batik. It embodies a centuries-old legac y of European colonial adventures, in both the Eastern and Southern hemispheres. So, the textile art's consumers define the stuff at least as much as its more invisible producers. Rather than Africans, however, the prosperous, largely anonymous European makers of the export cloth are the ones Shonibare dresses up in all their fine Victorian splendor. The friction sends off sparks. "A Flying Machine for Every Man, Woman and Child" is a charming, room-size tableau that might have popped out of an old children's book. Dad, Mom, Junior and Sis -- each dressed to the hilt in severely tailored jackets, bustles, ruffled skirts, knickers, boots and such -- are daintily posed on unicycles topped by multicolored, umbrella-like propellers. It's a fanciful depiction of a romantic ideal of individually powered freedom. And it looks absurd, like Mary Poppins on acid. The LA Times April 6 2009, Christopher Knight The foolishness is multifaceted, thanks first to Shonibare's exquisite exploitation of the textiles. No garment is made from one cloth pattern or a single color. Instead, a riot of colors and clanging collisions of luxurious patterns are stitched together, upending any presumptions of prim Victorian propriety. Showy, aggressive wealth propels this scenic fantasy of individual liberty, which is available only to some and certainly at a cost. Here it's prosperous Europeans who look exotic. The group is a classic nuclear family -- a thoroughly modern form of social organization -- and Shonibare gaily explodes its conventions. The headless family that plays together, stays together, even if they're all contradictorily headed in different directions. His funny flying mac hines, which will never get off the ground, are like antecedents to the modern automobile industry, with its own petro-fueled promises of Utopian mobility. The show is a concise introduction to Shonibare's work, built around the flying machine tableau (it was commissioned last year by Florida's Miami Art Museum). SBMA curator Julie Joyce added six other individual figures and tableaux made during the last decade, plus a 32-minute video, "Un Ballo in Maschera" (A Masked Ball) and a few other works. There's a brochure but no catalog. th The lush video is very loosely based on Sweden's King Gustav III: an elegant 18 century patron of literature and art, tellingly enacted here by a woman. Window-dressing merges with British costume drama, happily mined by artists including William Hogarth and David Hockney, not to mention by movies and TV. Like a fluttery flock of caged rare birds dancing a formally constricted minuet, Shonibare's wigged courtiers make beautiful mockery of Gus, an anti-reformer and absolute monarchist assassinated at Stockholm's Royal Opera during a masked ball. Three times the dancers replay the dramatic moments leading up to and including his shooting. Repetition reinforces the point that hyper-refinement and brute force are not mutually exclusive, while clichés of masculine and feminine behavior are just that -- clichés. The video-assassin is, like the king but unlike the actual one in history, a woman. The show also includes a remarkable recent work, "La Méduse" (2008), a large wood-and-glass display case with a meticulously crafted sailing ship on roiling high seas, tossed toward inevitable doom. It refers to Theodore Gericault's famous monumental painting, "The Raft of the Medusa" (1818-19), with its pile of dying, shipwrecked sailors. Gericault's painting dramatizes a notorious event, when a French frigate bound for Senegal to retake control of land occupied by the British sailed to its destruction in a violent storm. The officers grabbed a lifeboat, but nearly 150 crew members were left adrift for two weeks on a makeshift raft. The few who survived brought back stories of cannibalism. The scandal was that the ship's incompetent captain had pulled strings with French government cronies to get his job, in which scores of innocent working people died. A field-day for the newspapers, the story was the original "Heck of a job, Brownie" for the modern world. But Shonibare turns the journalistic tables. For his shocking display of official malfeasance and human disregard at the highest levels, paid for with the blood of those at the bottom, he shows us what Gericault did not: the metaphorical ship of state, its tattered sails made from brightly colored Dutch-wax fabric. The corrupt argument between French and British oligarchs over colonial spoils is enshrined as the episode's driving event, not the tabloid-ready distraction of cannibalism in its cruel aftermath. The LA Times April 6 2009, Christopher Knight "La Méduse" sets aside victimhood for a clear but no less dramatic look at what the perpetrators of the crime valued most. With its monumental display case the sculpture is ready-made for an art museum, the place where we proudly display civilization's great achievements. England's monarch awarded the artist the Order of the British Empire in 2005, and he now goes by Yinka Shonibare MBE. Yet one more wry transaction that is not quite what it might seem to be, the badge of honor soberly inc ludes him in the society his art appraises with such inc isive critical candor. "Yinka Shonibare MBE: A Flying Machine for Every Man, Woman and Child and Other Astonishing Works," Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1130 State St., (805) 963-4364, through June 21. Tues.-Sun., 11 a.m.-5 p.m.; $9; free on Sundays. www.sbma.net.