Dataset for the histopathological reporting of carcinomas of the

advertisement

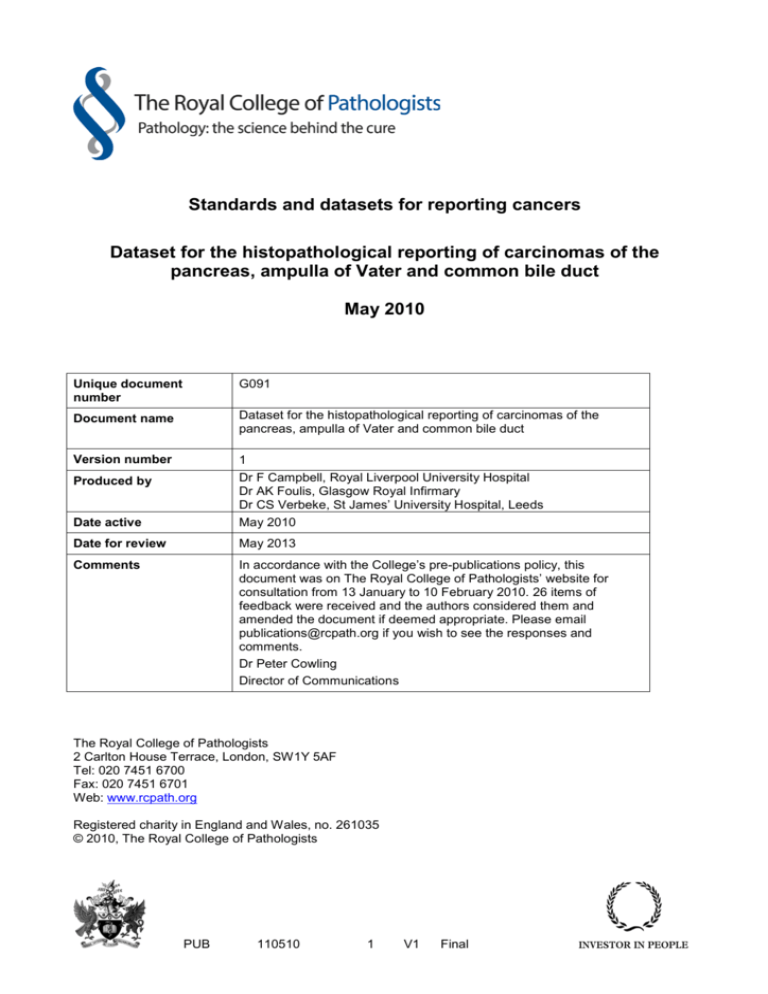

Standards and datasets for reporting cancers Dataset for the histopathological reporting of carcinomas of the pancreas, ampulla of Vater and common bile duct May 2010 Unique document number G091 Document name Dataset for the histopathological reporting of carcinomas of the pancreas, ampulla of Vater and common bile duct Version number 1 Produced by Dr F Campbell, Royal Liverpool University Hospital Dr AK Foulis, Glasgow Royal Infirmary Dr CS Verbeke, St James’ University Hospital, Leeds Date active May 2010 Date for review May 2013 Comments In accordance with the College’s pre-publications policy, this document was on The Royal College of Pathologists’ website for consultation from 13 January to 10 February 2010. 26 items of feedback were received and the authors considered them and amended the document if deemed appropriate. Please email publications@rcpath.org if you wish to see the responses and comments. Dr Peter Cowling Director of Communications The Royal College of Pathologists 2 Carlton House Terrace, London, SW1Y 5AF Tel: 020 7451 6700 Fax: 020 7451 6701 Web: www.rcpath.org Registered charity in England and Wales, no. 261035 © 2010, The Royal College of Pathologists PUB 110510 1 V1 Final Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 4 2. Clinical information required on specimen request form ........................... 5 3. Specimen handling and dissection ........................................................... 5 4. Core data items ....................................................................................... 7 5. Non-core data items................................................................................. 7 6. Notes on macroscopic assessment .......................................................... 8 7. Notes on microscopic assessment ........................................................... 10 8. Pathological staging ................................................................................. 13 9. Diagnostic coding .................................................................................... 13 10. Reporting of frozen sections .................................................................... 13 11. Criteria for audit and standards ................................................................ 14 12. References .............................................................................................. 14 Appendix A ICD-10 and SNOMED ‘T’ coding for tumour site ............................ 20 Appendix B WHO classification of malignant exocrine pancreatic tumours and SNOMED ‘M’ Codes .................................................................................. 21 Appendix C WHO classification of carcinomas of the ampulla of Vater and extrahepatic bile ducts and SNOMED ‘M’ codes ........................................ 22 Appendix D UICC TNM classification ................................................................ 23 Appendix E Proforma for pancreatic carcinoma ................................................ 24 Appendix F Proforma for ampulla of Vater carcinoma ....................................... 25 Appendix G Proforma for common bile duct carcinoma..................................... 26 Appendix H Periampullary cancer dataset monitoring sheet ............................. 27 PUB 110510 2 V1 Final Foreword The Cancer Datasets published by the Royal College of Pathologists are guidelines that should assist pathologists in providing a high standard of care for patients. Guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist the decisions of practitioners and patients about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances and are based on the best available evidence at the time the dataset was prepared. It may be necessary or even desirable to depart from the guidelines in the interests of specific patients and special circumstances. Just as adherence to the guidelines may not constitute defence against a claim of negligence, so deviation from them should not necessarily be deemed negligent. The dataset has been reviewed by the Cancer Services Working Group and placed on the College website for consultation with the membership between 13 January and 10 February 2010. All comments received from the Working Group and memberships have been addressed by the authors to the satisfaction of the chair of the Working Group and the Director of the Professional Standards Unit. No major organizational changes or costs have been identified that would hinder the implementation of the Dataset. Each year, the College will ask the authors of the Dataset, in conjunction with the relevant subspecialty advisor to the College, to consider whether or not the Dataset needs to be revised. This Dataset was developed without external funding to the writing group. The College requires the authors of datasets to provide a list of potential conflicts of interest; these are monitored by the Director of the Professional Standards Unit and are available on request. PUB 110510 3 V1 Final 1. Introduction 1.1 General background to the dataset Pathology reporting of pancreatic, ampulla of Vater and common bile duct cancers is important for the following reasons: a) to make or confirm the diagnosis b) to inform prognosis c) to select potential patients for future trials of adjuvant therapy d) to correlate with radiology and surgery e) to collect accurate data for cancer registration and epidemiology f) to allow the accurate and equitable comparison of surgical practice in different units and the comparison of patients in clinical trials. The number of resections for periampullary cancer has increased over the last 10 years. This has led to the identification of new pathological entities and investigation of numerous potential prognostic factors, the majority of which can only be assessed after surgery. Those histological tumour characteristics that have been reported (in most studies) to have significant prognostic value in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma include tumour size, tumour differentiation, lymph node involvement and resection margin status.1−7 Tumour stage and lymph node status are the most important prognostic factors identified to date for ampullary adenocarcinoma and common bile duct adenocarcinoma.8,9 1.2 Developments since the first edition was published Since the first edition of this dataset in 2002, there have been many requests for guidance particularly on dissection of the pancreatoduodenectomy specimen, identification of resection margins and definition of a positive resection margin. Many of these requests were sought following the British Society of Gastroenterology survey of ‘Pathologists' approach to pancreatectomies for ampullary, pancreatic and bile duct cancer’ published in 2009 (www.bsg.org.uk/sections/pancreas-news/pancreatic-section-survey.html). These requests have been addressed but it is emphasized that the dataset is for guidance and is not prescriptive. The reporting proformas and guidance are based on the WHO classifications of tumours of the exocrine pancreas, ampulla of Vater and extrahepatic bile duct10 and the UICC TNM staging system, 7th edition (2009).11 The UICC TNM staging system has the advantage of being widely accepted and familiar, and is adhered to throughout this document. The separation of extrahepatic bile duct cancers into perihilar and distal cancers in the 7th edition of the TNM staging system (2009) is welcomed. The new T classification and the definition of regional lymph nodes in distal bile duct cancers are much more appropriate for the common bile duct cancers removed by a standard Kausch-Whipple’s resection or a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. The T3 and T4 classifications for distal extrahepatic bile duct cancers, like those for pancreatic cancers, also reflect what is operable (T3) and what is deemed unresectable in most centres (T4). There have been no changes to the T classifications for cancers of the pancreas or ampulla of Vater since the 6th edition of the TNM staging system (2002). However, pMx and pMo have now been removed from the histopathological (pTNM) classification system in the 7th edition of the TNM staging system (2009). pM1 may be used when a distant metastasis is proven histologically. If a potential (cM1) metastasis is biopsied but is negative histologically, it is classed as cM0 but not pM0. These guidelines mainly apply to the reporting of pancreatic exocrine carcinomas, 90% of which are ductal adenocarcinomas, but similar principles may be applied to the reporting of carcinomas arising in the ampulla of Vater or common bile duct. The reporting of endocrine PUB 110510 4 V1 Final tumours is addressed in the separate Dataset for Endocrine Tumours of the Gastrointestinal Tract Including the Pancreas.12 1.3 Assessment of literature This document has been devised to include the data required for adequate reporting of pancreatic, ampulla of Vater or common bile duct specimens containing cancer. Where possible, core data that represent a minimum standard for patient management have been distinguished from non-core data that may form part of a complete report. The proformas may be used as the main reporting format or may be combined with free text as required. Evidence for the revised dataset was obtained from a review of relevant literature up to June 2009 using the PubMed and Medline databases. A consensus view was taken on selection of the information to be included, on grounds of robustness of evidence reinforced by the authors’ own experience. 1.4 Consultation with stakeholders Approval of the dataset has been sought from the Pancreas Society of Great Britain and Ireland, the Pancreatic Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology, the Pathology Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology, and panels of specialized and general histopathologists acting on behalf of the College. 2. Clinical information required on the specimen request form Whilst the nature of the resection is usually obvious to the pathologist from the specimen that is submitted to the laboratory, it is good practice to confirm this with the specimen request form. A diagram of the surgical procedure or a good clinical description is important for complex specimens. Patients often proceed to pancreatic surgery on the basis of imaging and/or cytology without a biopsy having been taken. Therefore, it is desirable for the pathologist to be told the presumed site and type of the tumour. 3. Specimen handling and dissection Resection specimens should, preferably, be opened and partially sectioned immediately after resection, to aid fixation. The margins of the pancreas (see Section 6.5) should be painted with an agreed colour code, either when the specimen is fresh or when fixed, according to the preference of the examining pathologist, but before blocks are taken. The presence of a stent or a named vessel (e.g. portal vein, superior mesenteric vein) should be noted. Identification of a resected vessel, particularly if small in size, may be facilitated by painting it with an extra colour. The specimen may then be pinned to a cork board but should be placed in a large volume of formalin and allowed to fix for 24−48 hours. Currently, several different techniques are used for dissecting pancreatoduodenectomy specimens.13 A detailed dissection protocol is beyond the scope of these guidelines. However, a brief discussion of the axial dissection method is included, because this technique has several advantages. After orientation of the specimen (Figure 1a), axial dissection (Figure 1b) serially slices the pancreatic head in an axial plane, i.e. perpendicular to the long axis of the duodenum. It is easy to perform, does not include longitudinal opening of the common bile duct or pancreatic duct, and allows key anatomical structures (e.g. ampulla, common bile duct, main pancreatic duct) to be seen in the same slices, which facilitates gross examination. This dissection technique usually results in 8−10 slices, allowing thorough examination of the tumour and its relationship to the key anatomical structures and margins. PUB 110510 5 V1 Final a b Figure 1 (a) Head of the pancreas and (b) axial dissection, i.e. slicing perpendicular to the long axis of the duodenum. SMV = superior mesenteric vein, SMA = superior mesenteric artery. (With acknowledgement to Paul Brown, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds.) For distal pancreatectomy specimens, the anterior and posterior surfaces may be painted, and the entire specimen can then be serially sliced in the sagittal plane. For total pancreatectomy specimens, a combined approach of axial slicing of the pancreatic head followed by serial slicing of the body and tail in the sagittal plane is recommended. Overview photographs of the lined-up specimen slices and close-up images of individual slices may be helpful for reporting (e.g. to identify the tumour origin), for multidisciplinary case discussion and for review of the gross findings if required (e.g. for audit or clinical trials). 3.1 Tissue sampling The transection margins of the pancreatic neck, common bile duct and duodenum/distal stomach are usually sampled (by en-face sections) prior to specimen dissection. Tissue blocks are taken to include the tumour where it approaches or involves anatomical structures relevant to (UICC TNM) T-staging, e.g. duodenum, ampulla, common bile duct or peripancreatic tissue. Similarly, samples should be taken from the tumour and the adjacent resection margin(s). It is often difficult to identify accurately the invasive tumour front macroscopically and, therefore, extensive sampling of the tumour and the adjacent margins is recommended.14 The importance of extensive sampling from the margins is supported by molecular studies.15,16 If available, sampling of one or more whole mount blocks may be helpful for assessing the relationship of the tumour to anatomical structures and to margins, as well as allowing accurate measurement of tumour dimensions. When a segmental resection of the portal/superior mesenteric vein is removed en-bloc with the pancreatoduodenectomy, then the proximal and distal ends of this vessel should be examined as additional transection margins. If a lateral sleeve resection of the vein is included in the specimen, then the entire edge of the vessel should be examined. PUB 110510 6 V1 Final All lymph nodes (Figure 2 and see Section 7.6) should be sampled, and samples of the ampulla of Vater, common bile duct and background pancreas should be taken. Figure 2 Lymph nodes. Inferior includes lymph nodes around superior mesenteric vessels. PPD = posterior pancreatoduodenal. 4. Core data items 4.1 Macroscopic • Type of specimen • Site of tumour • Maximum tumour dimension • Resection margins (measurement confirmed microscopically) • Named vessel present • Background pathology (e.g. intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, mucinous cystic neoplasm, adenoma of the ampulla) 4.2 Microscopic • Histological type of tumour • Tumour grade • Maximum extent of local invasion • Perineural invasion • Named vessel involvement • Lymph node status (number present, number involved) • Resection margin status • Distant metastases 4.3 Other • UICC TNM stage • Completeness of excision (R stage) • SNOMED codes 5. Non-core data items 5.1 Macroscopic • Specimen measurements for each organ included PUB 110510 7 V1 Final • • Stent in place Other organs 6. Notes on macroscopic assessment Measurements made on the gross specimen are recorded in millimetres. They are confirmed or amended, where appropriate, by microscopy. 6.1 Type of specimen The type of specimen should be recorded, e.g. a standard Kausch-Whipple’s pancreatoduodenectomy (PD), a pylorus-preserving PD, a total PD, a subtotal or left pancreatectomy. The standard Kausch-Whipple’s PD includes the head of pancreas, duodenum, common bile duct, gall bladder and two thirds of the stomach; the pyloruspreserving PD does not include the stomach; the total PD also includes the body and tail of pancreas with or without the spleen and/or stomach; the subtotal pancreatectomy includes the body of the pancreas with or without the stomach; and the left (or distal) pancreatectomy only consists of the body and tail of pancreas, with or without the spleen. The type of operation will depend upon the site and size of the tumour. Recent trials, single-centre studies and a Cochrane Database Systematic Review did not show any difference in patient survival between standard PD versus pylorus-preserving PD,17−20 PD with or without vascular resection,21 and PD with or without extended lymphadenectomy.22−24 6.2 Specimen measurements Record the lengths of the duodenum, stomach (lesser curve and greater curve), gall bladder, cystic duct and extrapancreatic bile duct, and the maximum dimensions of the pancreas. The diameters of the common bile duct and main pancreatic duct can indicate the location of an obstruction and are useful for correlation with radiology. 6.3 Site of tumour (Appendix A) State, when possible, whether the tumour arises in the ampulla of Vater, in the intrapancreatic or extrapancreatic bile duct, or in the head, body or tail of the pancreas. The precise origin of a tumour in the head of the pancreas may be difficult to determine, particularly when the tumour is large and involves more than one potential site of origin. The tumour origin may then be determined by the location of the centre of the tumour. Microscopic confirmation should be sought and, in some cases, the presence of microscopic precursor lesions may be helpful (adenoma or flat dysplasia in the ampulla, dysplasia in the bile duct). However, note that pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) is a frequent finding and can be found in the background pancreas of specimens with ampullary or bile duct cancer.25,26 Although immunohistochemistry may distinguish intestinal type carcinomas from biliary type carcinomas arising in the ampulla, there are currently no immunohistochemical markers that distinguish between biliary type carcinomas of the ampulla and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma. The head is that part of the pancreas to the right of the left border of the superior mesenteric vein; the uncinate process is considered part of the head; the body lies between the left border of the superior mesenteric vein and the left border of the aorta; and the tail lies between the left border of the aorta and the hilum of the spleen. Carcinomas of the body or tail are usually more advanced than those of the head at the time of diagnosis, because of lack of obstructive symptoms, and because they usually spread into extrapancreatic tissue and metastasize before detection. They are, therefore, seldom resected. Note that pancreatic carcinomas may be multicentric (fill in a separate proforma for each carcinoma). PUB 110510 8 V1 Final Macroscopic examination is essential for determining whether pancreatic adenocarcinoma has arisen in an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) or in a mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN).27 For IPMNs, the resection specimen should also be assessed to determine whether the IPMN is of main duct type, branch duct type or mixed/combined duct type, because of the better prognosis with branch duct IPMNs. 6.4 Tumour size Optimally, three dimensions should be measured but, for staging purposes, at least the maximum diameter of the tumour should be measured. The tumour size is based on macroscopic assessment but confirmed or amended on the basis of microscopy. Tumour size in pancreatic carcinoma is a prognostic factor in most studies, on either univariate or multivariate analysis.3−5 Pancreatic adenocarcinomas < 2 cm in size are associated with better survival.28,29 Note, however, that lymph node metastasis and portal vein or resection margin involvement can be seen in small pancreatic (< 2 cm) tumours.30 6.5 Distance from tumour to nearest margin Completeness of excision should be assessed macroscopically and be confirmed by microscopic examination. The transection margins are those of the pancreatic neck, common bile duct and stomach/duodenum. The dissected margins are the superior mesenteric vessel (sometimes referred to as the medial or uncinate) margin and the posterior margin (Figure 1a and Figure 3). The superior mesenteric vessel margin includes the superior mesenteric vein margin (defined as the smooth groove-like surface facing the superior mesenteric vein) and the superior mesenteric artery margin (defined as the rough area to the left of the superior mesenteric vein margin and facing the superior mesenteric artery) (Figure 1a). The posterior margin is defined as the fibrous but smooth surface of the pancreatic head overlying the aorto-caval groove. Figure 3 Resection margins for the head of the pancreas. The anterior surface of the pancreas is not a surgical margin but invasion of this surface has been shown to be associated with local recurrence and decreased survival time.31−34 PUB 110510 9 V1 Final 7. Notes on microscopic assessment 7.1 Tumour type The histological classification is based on the WHO typing of tumours of the exocrine pancreas, ampulla of Vater and extrahepatic bile duct10 (Appendices B and C). Ductal adenocarcinoma, including its variants, accounts for 90% of the pancreatic tumours. Recognition of the variants of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is important because they can differ in clinical behaviour, e.g. colloid carcinoma has a significantly better prognosis than conventional PDAC.35 Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells is now considered a variant of PDAC. Other recently described variants of PDAC include clear cell carcinoma,36 foamy gland carcinoma37 and intestinal type adenocarcinoma.38 It is important to recognize and state whether adenocarcinoma has arisen from a mucinous cystic neoplasm (when the invasive tumour is typically a tubular/ductal type carcinoma) or from an IPMN (when the invasive carcinoma may be tubular/ductal type or colloid type).27 This is because the 5-year survival rates for resected mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) and IPMNs with associated invasive carcinoma can be much better than for conventional non-MCN/non-IPMN associated ductal adenocarcinoma.39−43 Adenocarcinomas originating in the ampulla of Vater may have intestinal and/or pancreatobiliary differentiation. Ampullary carcinomas of intestinal type behave like duodenal adenocarcinomas, while those of pancreatobiliary type behave like pancreatic adenocarcinoma and are associated with a poorer prognosis.44−46 7.2 Tumour grade Histological grading of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma into well, moderately and poorly differentiated, according to the criteria of Klöppel et al47 (Table 1), has been found to be of prognostic significance, on univariate and/or multivariate analysis, in most studies.1,4,48,49 The tumour is graded according to the least differentiated area, regardless of prevalence. A more recently proposed grading system for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, which uses a scheme similar to the Gleason scoring system, has been shown to have prognostic value but awaits further evaluation.50 TABLE 1 Histological grading of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma47 Differentiation Well Moderate Poor Duct structures Well formed Nuclei Some well formed Very irregular or absent Loss of polarization, anisonucleosis Marked anisonucleosis, clumped chromatin Basal 47 *High power field of Klöppel et al 7.3 Mitotic figures per 10 high power fields* <5 measured 1356 µm Mucin production Marked 5−10 Variable > 10 Minimal 2 Local invasion UICC TNM staging for pancreatic carcinoma requires assessment of the maximum size of the tumour and whether or not tumour extends beyond the pancreas (Appendix D). The UICC pT stage correlates well with prognosis.51 Peripancreatic tissue invasion has been reported in up to 90% of cases52 and correlates with poor prognosis. Note that involvement of the intrapancreatic common bile duct by pancreatic carcinoma should be staged as pT3. PUB 110510 10 V1 Final The UICC TNM staging of carcinomas of the distal extrahepatic bile duct and ampulla of Vater is different from that of pancreatic carcinoma (Appendix D).11 7.4 Neural invasion Perineural invasion is a histological characteristic of pancreatic carcinoma. There is a significant correlation between intrapancreatic neural invasion and extrapancreatic plexus invasion,53 which is a major cause of local recurrence. Although the frequency of perineural invasion differs between studies, it still remains a significant prognostic factor for periampullary carcinoma.54−58 7.5 Vascular invasion Large named-vessel involvement is a factor determining survival. Radiological evidence of tumour extension into the coeliac axis (i.e. T4 tumour, Appendix D) is a contraindication for surgery. Resection of pancreatic carcinoma infiltrating the superior mesenteric artery or hepatic artery is technically possible and performed in some European and American centres.21 However, it is currently a contraindication for surgery in the UK. Named-venous involvement (i.e. portal vein or superior mesenteric vein) is not a contraindication to surgery, provided venous reconstruction is possible. Involvement is diagnosed when there is a segment of vein wall attached to the resection specimen that is clearly infiltrated by tumour on histological examination. In a significant proportion of cases, however, there is no histological evidence of tumour invasion of the resected vessel wall, and the tethering of the vessel is caused by fibro-inflammatory changes. Controversy still exists as to whether the presence or absence of microscopic tumour infiltration of the vessel wall influences survival.21,58,59 7.6 Lymph node spread Multivariate analysis has shown lymph node involvement to be a negative prognostic indicator in pancreatic carcinoma.4,60−62 However, the lymph node ratio (the ratio of the number of lymph nodes with metastatic cancer to the total number of lymph nodes examined) is now considered a more powerful prognostic marker than the overall nodal status in resected pancreatic cancer.63−65 In ampullary carcinoma, lymph node involvement and the lymph node ratio are also independent prognosticators on multivariate analysis.66,67 Although lymph node involvement in ampullary carcinoma is associated with a poorer prognosis, survival figures are still better than for node-positive pancreatic adenocarcinoma. In extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma, increasing numbers of lymph node metastases are also associated with poorer survival.68,69 The regional lymph nodes (Figure 2) for the pancreas and ampulla of Vater can be grouped into anterior pancreatoduodenal, posterior pancreatoduodenal, inferior (including the lymph nodes around the superior mesenteric vessels), common bile duct, infrapyloric (for tumours of head of pancreas or ampulla), superior and (not shown in Figure 2) proximal mesentery.11 Coeliac lymph nodes (sent separately) are regional lymph nodes for tumours of the head of the pancreas only. Lymph nodes in the hilum of the spleen and tail of the pancreas are regional lymph nodes for tumours of the body and tail only. The regional lymph nodes for the distal extrahepatic bile duct are along the common bile duct, common hepatic artery, back towards the coeliac trunk, posterior and anterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes, and nodes along the superior mesenteric vein and the right lateral wall of the superior mesenteric artery.11 In the Japan Pancreas Society (JPS) classification of lymph node stations,70 numbers are given to these groups of lymph nodes (Table 2). Lymph nodes 8 (around the common hepatic artery) and 16 (para-aortic) may be sent with pancreatoduodenectomy specimens. PUB 110510 11 V1 Final All of the lymph nodes that are identified in the specimen should be examined histologically. A Whipple's resection should yield a minimum of 15 lymph nodes from the main specimen.3,65 The number of retrieved/evaluated lymph nodes has been shown to influence survival.67,71,72 Direct extension of the primary tumour into lymph nodes is classified as lymph node metastasis.11 TABLE 2 Japan Pancreas Society (JPS) classification of lymph node stations.70 JPS node stations 6 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 16 17 18 Equivalent UICC node stations Infrapyloric Common hepatic artery Coeliac Splenic hilum Superior/along splenic artery Hepatoduodenal ligament (portal/bile duct) Posterior pancreatoduodenal Superior mesenteric vessel Para-aortic Anterior pancreatoduodenal Inferior In one study, immunohistochemistry to detect micrometastases in haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained tumour-free lymph nodes has shown that nodal micro-involvement is an independent adverse prognostic factor on multivariate analysis.73 However, the use of immunohistochemistry is not currently recommended for routine practice. 7.7 Margins The rates of microscopic margin involvement (R1) vary markedly between studies. Although resection margin status is believed to be a key prognostic factor, the rates of margin involvement and local tumour recurrence are often incongruous.1,3,5,6,65,74 The disparities in R1 rate and its prognostic value may be due to differences in opinion on what constitutes a resection margin, controversy over the definition of microscopic margin involvement, and lack of standardization of the histopathology examination of pancreatoduodenectomy specimens.13 When a fully standardized, detailed pathology examination protocol is used, microscopic margin involvement is a common finding in pancreatic carcinoma (> 75%) and correlates with survival.7,14,75,76 The rate of margin involvement in common bile duct carcinoma is similar to that for pancreatic carcinoma, but is less common in ampullary carcinoma.76−80 The posterior and superior mesenteric vessel margins are the most frequently involved margins in pancreatic carcinoma.7,14,75,76 Currently, there is controversy over the adequate minimum clearance for pancreatic, common bile duct and ampullary carcinoma. While some pathologists define margin involvement when carcinoma is present at the margin (i.e. 0 mm clearance), others use the 1 mm rule adopted from margin assessment in rectal carcinoma. It has been shown in two recent studies that there is no significant difference in survival for those patients with carcinoma less than 1 mm from a margin compared to those with direct tumour involvement of a resection margin.75,81 Carcinoma less than 1 mm from a resection margin is considered to be incompletely excised, while further studies on this are awaited. Since the anterior surface of the pancreatic head is an anatomical surface rather than a surgical margin, it would seem appropriate to apply the 0 mm clearance rule for the assessment of the anterior surface. When there is no direct margin involvement by tumour, it is unclear whether those rare cases in which tumour cells are found within lymph nodes, lymphovascular channels or PUB 110510 12 V1 Final perineural clefts at, or less than 1 mm, from a resection margin should be classed as R1 resections.13 In the UICC TNM classification, when tumour cells are found in the lumen of a lymphovascular channel at the resection margin, without contact with the endothelium, the classification is R0.82 When tumour is attached to the vessel wall or invades the vessel wall at the resection margin, a classification of R1 is appropriate.82 In the current absence of evidence about lymph node or perineural involvement at a resection margin, it is suggested that such margin involvement should be considered as incomplete excision if it is the only reason to report a case as a R1 resection, but this should be clearly stated in the report. 7.8 Distant metastases The presence of histologically confirmed distant metastases (pM1) and their site should be recorded. Metastases to the liver, peritoneum, omentum or extra-abdominal contraindications for resection in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.31 7.9 sites are Background pathology As stated in Section 6.3, the presence of microscopic precursor lesions (e.g. adenoma, flat dysplasia) may be helpful in determining the primary origin of a tumour. PanINs25 are the most common precursors to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma but are a frequent finding in all resected pancreata, i.e. including resections for non-neoplastic disease.25,26 The presence of an underlying IPMN or MCN should always be stated.83,84 7.10 Other markers A number of molecular markers, such as k-ras, SMAD4, S100A6 and cyclin E, have been shown to be of prognostic value following resection, but inclusion of these into routine practice is currently not justified.15,16,85−88 8. Pathological staging Multivariate analysis shows that tumour stage is the most significant factor in predicting long-term survival in pancreatic carcinoma.51 The UICC TNM classification obtained from the histopathological data can be converted to a stage grouping,11 but full clinical data will need to be taken into account before the final stage can be determined. 9. Diagnostic coding Tumours should be coded according to the SNOMED system (see Appendices A-C). 10. Reporting of frozen sections Histological confirmation of the primary diagnosis, assessment of the presence or absence of carcinoma or IPMN at the pancreatic transection margin, the presence of carcinoma at the bile duct margin, or histological confirmation of a potentially metastatic nodule in the liver, peritoneum or a lymph node are the commonest indications for intraoperative frozen section diagnosis.89 Distinction between a liver metastasis and a bile duct hamartoma/adenoma may prove problematic. The presence of necrosis, irregularity of ducts and mitoses in ducts, all favour a diagnosis of malignancy. The distinction between pancreatitis and adenocarcinoma in the pancreas may also be difficult on frozen section, because of cautery or freezing artefacts, or the distortion and reactive nuclear atypia in small residual ductules in chronic pancreatitis. Often a low power microscopic view is most useful in order to appreciate the PUB 110510 13 V1 Final lack of a lobular distribution of the ducts and the irregularity of duct outline in carcinoma of the pancreas. Occasionally, the distinction between invasive ductal adenocarcinoma and PanIN-3 in a background of atrophy at the transection margin can be problematic, but this is of limited practical importance since the latter diagnosis is likely to result in the removal of additional tissue if feasible.90 Similarly, the presence of high grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma within an IPMN at the transection margin will usually lead to further resection. 11. Criteria for audit and standards It is recommended that multidisciplinary teams and/or pathology departments audit their pathology reports at regular intervals (perhaps yearly) to ensure the completeness of data within pathology reports. As regards the standard of pathology, there is currently little evidence on the frequencies with which important adverse prognostic features are found between individual pathologists and multidisciplinary teams. However, it has been shown that the mean harvest of lymph nodes from a Whipple’s resection should be at least 15 nodes3,65 and that the number of retrieved/evaluated lymph nodes does influence survival.67,71,72 Therefore, to evaluate the standard of pathology dissection, it is recommended that in a series of Whipple’s resections for carcinoma, the mean number of lymph nodes examined should be 15. As more evidence accumulates, it may be possible to adjust this level and to introduce other outcome measures for pathology. 12. References 1. Benassai G, Mastrorilli M, Quarto G, Cappiello A, Giani U, Forestieri P et al. Factors influencing survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol 2000;73:212−218. Cleary SP, Gryfe R, Guindi M, Greig P, Smith L, Mackenzie R et al. Prognostic factors in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: analysis of actual 5 year survivors. J Am Coll Surg 2004;198:722−731. Han SS, Jang JY, Kim SW, Kim WH, Lee KU, Park YH. Analysis of long-term survivors after surgical resection for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 2006;32:271−275. Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1199−1210. Moon HJ, An JY, Heo JS, Choi SH, Joh JW, Kim YI. Predicting survival after surgical resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2006;32:37−43. Raut CP, Tseng JF, Sun CC, Wang H, Wolff RA, Crane CH et al. Impact of resection status on pattern of failure and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2007;246:52−60. Esposito I, Kleeff J, Bergmann F, Reiser C, Herpel E, Friess H et al. Most pancreatic cancer resections are R1 resections. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1651−1660. Fisher WE, Bakey ME. Differences between ampullary, periampullary and pancreatic cancer. World J Surg 2007;31:144−146. Hong SM, Cho H, Lee O, Ro JY. The number of metastatic lymph nodes in extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma as a prognostic factor. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1177−1183. Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press, 2000. Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind Ch (eds). International Union Against Cancer TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours (7th edn). Wiley Blackwell, 2009. Stephenson TJ, Cross SS, Williams GT. Dataset for Endocrine Tumours of the Gastrointestinal Tract Including Pancreas. London: Royal College of Pathologists, 2009. Verbeke CS. Resection margins and R1 rates in pancreatic cancer – are we there yet? Histopathology 2008;52:787−796. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. PUB 110510 14 V1 Final 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. PUB Verbeke CS, Leitch D, Menon KV, McMahon MJ, Guillou PJ, Anthoney A. Redefining the R1 resection in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2006;93:1232−1237. Ohigashi H, Ishikawa O, Sasaki Y, Yamada T, Furukawa H, Imaoka S et al. K-ras point mutation in the nerve plexuses around the superior mesenteric artery in resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head: distribution pattern and related factors. Arch Surg 2000;135:1450−1455. Kim J, Reber HA, Dry SM, Elashoff D, Chen SL, Umetani N et al. Unfavourable prognosis associated with K-ras gene mutation in pancreatic cancer surgical margins. Gut 2006;55:1598−1605. Diener MK, Heukäufer C, Schwarzer G, Seiler CM, Antes G, Buchler MW et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (classic Whipple) versus pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pp Whipple) for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 Apr 16;(2):CD006053. Lin PW, Lin YJ. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 1999;86:603–607. Seiler C, Wagner M, Bachmann T, Redaelli CA, Schmied B, Uhl W et al. Randomized clinical trial of pylorus-preserving duodenopancreatectomy versus classical Whipple resection – long term results. Br J Surg 2005;92:547−556. Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Kazemier G, Hop WC, Greve JW et al. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: a prospective randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic or periampullary tumors. Ann Surg 2004;240:738−745. Yekebas EF, Bogoevski D, Cataldegirmen G, Kunze C, Marx A, Vashist YK et al. En bloc vascular resection for locally advanced pancreatic malignancies infiltrating major blood vessels: perioperative outcome and long-term survival in 136 patients. Ann Surg 2008;247:300−309. Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sohn TA, Campbell KA, Sauter PK et al. pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg 2002;236:355–368. Pedrazzoli S, DiCarlo V, Dionigi R, Mosca F, Pederzoli P, Pasquali C et al. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Lymphadenectomy Study Group. Ann Surg 1998;228:508– 517. Farnell MB, Aranha GV, Nimura Y, Michelassi F. The role of extended lymphadenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: strength of the evidence. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:651−656. Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Compton C, Garrett ES, Goodman SN et al. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a new nomenclature and classification system for pancreatic duct lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:579−586. Agoff SN, Crispin DA, Bronner MP, Dail DH, Hawes SE, Haggitt RC. Neoplasms of the ampulla of Vater with concurrent pancreatic intraductal neoplasia: a histological and molecular study. Mod Pathol 2001;14:139−146. Campbell F, Azadeh B. Cystic neoplasm of the exocrine pancreas. Histopathology 2008;52:539−551. Yamaguchi K, Mizumoto K, Noshiro H, Sugitani A, Shimizu S, Chijiiwa K et al. Pancreatic carcinoma: < or = 2 cm versus > 2 cm in size. Int Surg 1999;84:213−219. Phoa SS, Tilleman EH, van Delden OM, Bossuyt PM, Gouma DJ, Laméris JS. Value of CT criteria in predicting survival in patients with potentially resectable pancreatic head carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2005;91:33−40. Furukawa H, Okada S, Saisho H, Ariyama J, Karasawa E, Nakaizumi A et al. Clinicopathologic features of small pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A collective study. Cancer 1996;78:986−990. 110510 15 V1 Final 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. PUB Doi R, Kami K, Ito D, Fujimoto K, Kawaguchi Y, Wada M, et al. Prognostic implication of para-aortic lymph node metastasis in resectable pancreatic cancer. World J Surg 2007;31:147−154. Nagakawa T, Nagamori M, Futakami F, Tsukioka Y, Kayahara M, Ohta T et al. Results of extensive surgery for pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 1996;77:640−645. Tsuchiya R, Noda T, Harada N, Miyamoto T, Tomioka T, Yamamoto K et al. Collective review of small carcinomas of the pancreas. Ann Surg 1986;203:77−81. Nagakawa T, Sanada H, Inagaki M, Sugama J, Ueno K, Konishi I et al. Long-term survivors after resection of the head of the pancreas: significance of histologically curative resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2004;11:402−408. Adsay NV, Pierson C, Sarkar F, Abrams J, Weaver D, Conlon KC et al. Colloid (mucinous non-cystic) carcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:26−42. Ray S, Lu Z, Rajendiran S. Clear cell ductal adenocarcinoma of pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004;128:693−696. Adsay NV, Logani S, Sarkar F, Crissman J, Vaitkevicius V. Foamy gland pattern of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a deceptively benign-appearing variant. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:493−504. Albores-Saavedra J, Simpson K, Dancer YJ, Hruban R. Intestinal type adenocarcinoma: a previously unrecognized histologic variant of ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Diagn Pathol 2007;11:3−9. Wilentz RE, Albores-Saavedra J, Hruban RH. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Semin Diagn Pathol 2000;17:31−42. Maire F, Hammel P, Terris B, Paye F, Scoazec JY, Cellier C et al. Prognosis of malignant intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas after surgical resection. Comparison with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2002;51:717−722. Adsay NV. The “new kid on the block”: Intraductal papillary neoplasms of the pancreas: current concepts and controversies. Surgery 2003;133:459−463. Salvia R, Fernández-del Castillo C, Bassi C, Thayer SP, Falconi M, Mantovani W et al. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg 2004;239:678−687. Rodriguez JR, Salvia R, Crippa S, Warshaw AL, Bassi C, Falconi M et al. Branch duct intraductal papillary neoplasms: observations in 145 patients who underwent resection. Gastroenterology 2007;133:72−79. Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra DS. Malignant epithelial tumors of the ampulla. In: Atlas of Tumor. Pathology, Tumors of the Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Bile Ducts, and Ampulla of Vater. Washington DC: AFIP, 2000. Carter JT, Grenert JP, Rubenstein L, Stewart L, Way LW. Tumors of the ampulla of vater: histopathologic classification and predictors of survival. J Am Coll Surg 2008;207:210−218. Westgaard A, Tafjord S, Farstad IN, Cvancarova M, Eide TJ, Mathisen O et al. Pancreatobiliary versus intestinal histologic type of differentiation is an independent prognostic factor in resected periampullary adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2008;8:170. Klöppel G, Lingenthal G, von Bülow M, Kern HF. Histological and fine structural features of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas in relation to growth and prognosis: studies in xenografted tumours and clinico-pathological correlation in a series of 75 cases. Histopathology 1985;9:841−856. Kuhlmann KF, de Castro SM, Wesseling JG, ten Kate FJ, Offerhaus GJ, Busch OR et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma; actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:549−558. Shoup M, Conlon KC, Klimstra D, Brennan MF. Is extended resection for adenocarcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas justified? J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:946−952. Adsay NV, Basturk O, Bonnett M, Kilinc N, Andea AA, Feng J et al. A proposal for a new and more practical grading scheme for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:724−733. 110510 16 V1 Final 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. PUB Isaji S, Kawarada Y, Uemoto S. Classification of pancreatic cancer: comparison of Japanese and UICC classifications. Pancreas 2004;28:231−234. Lüttges J, Vogel I, Menke M, Henne-Bruns D, Kremer B, Klöppel G. The retroperitoneal resection margin and vessel involvement are important factors determining survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Virchows Arch 1998;433:237−242. Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Konishi I, Ueno K, Ohta T, Miyazaki I. Clinicopathological study of pancreatic carcinoma with particular reference to the invasion of the extrapancreatic neural plexus. Int J Pancreatol 1991;10:105−111. Ozaki H, Hiraoka T, Mizumoto R, Matsuno S, Matsumoto Y, Nakayama T et al. The prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and intrapancreatic perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer after curative resection. Surg Today 1999;29:16−22. Bouvet M, Gamagami RA, Gilpin EA, Romeo O, Sasson A, Easter DW et al. Factors influencing survival after resection for periampullary neoplasms. Am J Surg 2000;180:13−17. Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, Seiler CA, Friess H, Büchler MW et al. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2004;91;586−594. Shimada K, Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Kosuge T, Hiraoka N. Reappraisal of the clinical significance of tumor size in patients with pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Pancreas 2006;33:233−239. van Roest MH, Gouw AS, Peeters PM, Porte RJ, Slooff MJ, Fidler V et al. Results of pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with periampullary adenocarcinoma: perineural growth more important prognostic factor than tumor localization. Ann Surg 2008;248:97−103. Tseng JF, Tamm EP, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Evans DB. Venous resection in pancreatic cancer surgery. Best Prac Res Clin Gastroenterol 2006;20:349−364. Shimada K, Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Kosuge T. Prognostic factors after distal pancreatectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the body and tail. Surgery 2006;139:288−295. Ferrone CR, Finkelstein DM, Thayer SP, Muzikansky A, Fernandez-delCastillo C, Warshaw AL. Perioperative CA19-9 levels can predict stage and survival in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2897−2902. Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Sarr MG, Smyrk TC, Zhang L, Qin R et al. Long-term survival after pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: is cure possible? Ann Surg 2008;247:456−462. Berger AC, Watson JC, Ross EA, Hoffman JP. The metastatic/examined lymph node ratio is an important prognostic factor after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2004;70:235−240. Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Cameron JL, Winter JM, Assumpcao L, Lillemoe KD et al. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Surgery 2007;141:610−618. Sierzega M, Popiela T, Kulig J, Nowak K. The ratio of metastatic/resected lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor in patients with node-positive pancreatic head cancer. Pancreas 2006;33:240−245. Brown KM, Tompkins AJ, Yong S, Aranha GV, Shoup M. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is curative in the majority of patients with node-negative ampullary cancer. Arch Surg 2005;140:529−533. Falconi M, Crippa S, Dominguez I, Barugola G, Capelli P, Marcucci S et al. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio and number of resected nodes after curative resection of ampulla of Vater carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:3178−3186. Hong SM, Cho H, Lee OJ, Ro JY. The number of metastatic lymph nodes in extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma as a prognostic factor. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1177−1183. Gomez D, Menon KV, Smith AM, Verbeke CS. Tumour location and number of positive lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors in distal bile duct cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10:227. 110510 17 V1 Final 70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. 77. 78. 79. 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. 85. 86. 87. 88. 89. PUB Japan Pancreas Society. Classification of Pancreatic Carcinoma (2nd English edn), Tokyo: Kanehara & Co. Ltd, 2003. Tomlinson JS, Jain S, Bentrem DJ, Sekeris EG, Maggard MA, Hines OJ et al. Accuracy of staging node-negative pancreas cancer: a potential quality measure. Arch Surg 2007;142:767−774. Schwarz RE, Smith DD. Extent of lymph node retrieval and pancreatic cancer survival: information from a large US population database. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1189−1200. Bogoevski D, Yekebas EF, Schurr P, Kaifi JT, Kutup A, Erbersdobler A et al. Mode of spread in the early phase of lymphatic metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: prognostic significance of nodal microinvolvement. Ann Surg 2004;240:993−1001. Jarufe NP, Coldham C, Mayer AD, Mirza DF, Buckels JA, Bramhall SR. Favourable prognostic factors in a large UK experience of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas and periampullary region. Dig Surg 2004;21:202−209. Campbell F, Smith RA, Whelan P, Sutton R, Raraty M, Neoptolemos JP et al. Classification of R1 resections for pancreatic cancer: the prognostic relevance of tumour involvement within 1 mm of a resection margin. Histopathology 2009;55:277−283. Menon KV, Gomez D, Smith AM, Anthoney A, Verbeke CS. Impact of margin status on survival following pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer: the Leeds Pathology Protocol (LEEPP). HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:18−24. van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, Offerhaus GJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, Obertop H et al. Survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma: an update. Eur J Surg Oncol 2001;27:549−557. de Castro SM, van Heek NT, Kuhlmann KF, Busch OR, Offerhaus GJ, van Gulik TM et al. Surgical management of neoplasms of the ampulla of Vater: local resection or pancreatoduodenectomy and prognostic factors for survival. Surgery 2004;136:994−1002. Katz MH, Bouvet M, Al-Refaie W, Gilpin EA, Moossa AR. Non-pancreatic periampullary adenocarcinomas: an explanation for favorable prognosis. Hepatogastroenterology 2004;51:842−846. Schmidt CM, Powell ES, Yiannoutsos CT, Howard TJ, Wiebke EA, Wiesenauer CA et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a 20-year experience in 516 patients. Arch Surg 2004;139:718−727. Van den Broeck A, Sergeant G, Ectors N, Van Steenbergen W, Aerts R, Topal B. Patterns of recurrence after curative resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009;35:600−604. Wittekind C, Compton CC, Greene FL, Sobin LH. TNM residual tumour classification revisited. Cancer 2002;94:2511−2516. Hruban RH, Takaori K, Klimstra DS, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Biankin AV et al. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal pancreatic mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:977−987. Katabi N, Klimstra DS. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical and pathological features and diagnostic approach. J Clin Pathol 2008;61:1303−1313. Kawesha A, Ghaneh P, Andrén-Sandberg A, Ograed D, Skar R, Dawiskiba Set et al. K-ras oncogene subtype mutations are associated with survival but not expression of p53, p16(INK4A), p21(WAF-1), cyclin D1, erbB-2 and erbB-3 in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 2000;89:469−474. Tascilar M, Skinner HG, Rosty C, Sohn T, Wilentz RE, Offerhaus GJ et al. The SMAD4 protein and prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2001;7:4115−4121. Vimalachandran D, Greenhalf W, Thompson C, Lüttges J, Prime W, Campbell F et al. High nuclear S100A6 (Calcyclin) is significantly associated with poor survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Res 2005;65:3218−3225. Skalicky DA, Kench JG, Segara D, Coleman MJ, Sutherland RL, Henshall SM et al. Cyclin E expression and outcome in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:1941−1947. Cioc AM, Ellison EC, Proca DM, Lucas JG, Frankel WL. Frozen section diagnosis of pancreatic lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:1169−1173. 110510 18 V1 Final 90. PUB Sharma S, Green KB. The pancreatic duct and its arteriovenous relationship: an underutilized aid in the diagnosis and distinction of pancreatic adenocarcinoma from intraepithelial neoplasia. A study of 126 pancreatectomy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:613−620. 110510 19 V1 Final APPENDIX A ICD-10 and SNOMED ‘T’ coding for tumour site Tumour site ICD-10 SNOMED code Head of pancreas Body of pancreas Tail of pancreas Whole pancreas Extrahepatic bile ducts Ampulla of Vater C25.0 C25.1 C25.2 C25.8 C24.0 C24.1 T-65100 T-65200 T-65300 T-65000 T-64000 T-64700 PUB 110510 20 V1 Final APPENDIX B WHO classification of malignant exocrine pancreatic tumours10 and SNOMED ‘M’ codes Ductal adenocarcinomaa Mucinous non-cystic carcinoma (colloid adenocarcinoma) Signet-ring cell carcinoma Adenosquamous carcinoma Undifferentiated (anaplastic or sarcomatoid) carcinoma Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells Mixed ductal−endocrine carcinoma SNOMED code M85003 M84803 M84903 M85603 M80203 M80353 M81543 Serous cystadenocarcinoma M84413 Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (non-invasive)b Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (invasive)c M84702 M84703 Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma (non-invasive)d Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma (invasive)e M84532 M84533 Acinar cell carcinoma Acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma Mixed acinar−endocrine carcinoma M85503 M85513 M81543 Pancreatoblastoma M89713 Solid-pseudopapillary carcinoma M84523 10 NOTE: Since the publication of the WHO classification in 2000 (a) new variants of ductal adenocarcinoma have been identified (e.g. hepatoid carcinoma, medullary carcinoma) and new terminology has been introduced for the mucinous neoplasms; (b) mucinous cystic neoplasm (carcinoma in situ), (c) mucinous cystic neoplasm with invasive carcinoma, (d) intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (carcinoma in situ) and (e) intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with invasive carcinoma. An oncocytic variant of intraductal papillary neoplasm has also been described, as has an intraductal tubular neoplasm. PUB 110510 21 V1 Final APPENDIX C WHO classification of carcinomas of the ampulla of Vater and extrahepatic bile ducts10 and SNOMED ‘M’ codes SNOMED code M81403 M82603 M81443 M81453 M84803 M83103 M84903 M85603 M80703 M80413 M80203 M82443 Adenocarcinoma (NOS) Papillary adenocarcinoma Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type Adenocarcinoma, gastric foveolar type Mucinous adenocarcinoma Clear cell adenocarcinoma Signet-ring cell carcinoma Adenosquamous carcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma Small cell carcinoma Undifferentiated carcinoma Mixed carcinoid−adenocarcinoma PUB 110510 22 V1 Final APPENDIX D UICC TNM histopathological classification11 General Pancreas TX T0 Tis Primary tumour cannot be assessed histologically No histological evidence of primary tumour Carcinoma in situ NX N0 N1 Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed histologically No regional lymph node metastasis histologically Regional lymph node metastasis histologically* M1 Distant metastasis confirmed histologically T1 Tumour limited to the pancreas, 20 mm or less in greatest dimension Tumour limited to the pancreas, more than 20 mm in greatest dimension Tumour extends beyond pancreas, but without involvement of coeliac axis or superior mesenteric artery Tumour involves coeliac axis or superior mesenteric artery T2 T3 T4 Ampulla of Vater T1 T2 T3 T4 Tumour limited to ampulla of Vater or sphincter of Oddi Tumour invades duodenal wall Tumour invades pancreas Tumour invades peripancreatic soft tissues, or other adjacent organs or structures Distal extrahepatic bile duct T1 Tumour confined to the bile duct T2 T3 Tumour invades beyond the wall of the bile duct Tumour invades the gall bladder, liver, pancreas, duodenum, or other adjacent organs Tumour involves the coeliac axis or the superior mesenteric artery T4 *For regional lymph nodes, see Section 7.6 PUB 110510 23 V1 Final APPENDIX E PROFORMA FOR PANCREATIC CARCINOMA Surname: ........................ Forenames: ............................ Date of birth: ....…......... Hospital: .................……. Hospital no: ...............………… NHS no: ......……..…..... Date of receipt: ……....... Date of reporting:……..…....... Sex: ....………................ Pathologist: …………..... Surgeon: ……………………… Report no:..………….….. Specimen type ……………………………………………………………………………………… Gross description Length of duodenum (mm) …… Length of lesser curve (mm)………. Length of greater curve (mm)….…... Length of gall bladder (mm) ……. Length of bile duct (mm)……... Size of pancreas (mm)……… x ……… x ……… Site of tumour ……………………..……… Maximum tumour diameter (mm) …….…. Other organs …………………..………….. Named vessel identified Yes No Which vessel? ……………………………… Stent in place Yes No Type of tumour: Ductal adenocarcinoma Other Differentiation Well Moderate (specify) .…………………...…….. Poor Maximum depth of invasion (T) Tumour involvement of margins Yes (R1) No (R0) Tis: Carcinoma in situ Transection margin T1: Tumour limited to the pancreas, 20 mm (gastric, duodenal, pancreatic, bile duct) or less in greatest dimension Dissection margin (SMV, SMA, posterior) T2: Tumour limited to the pancreas, more than Anterior pancreatic surface 20 mm in greatest dimension Which margins involved (specify)?....................................... T3: Tumour extends beyond pancreas but without involvement of coeliac axis or SMA T4: Tumour involves coeliac axis or SMA Perineural invasion Yes No Named vessel involved Lymph node involvement (N) Total number of nodes ……… Number of nodes involved ……… NX: Cannot be assessed N0: Regional lymph nodes not involved N1: Regional lymph nodes involved Distant metastasis (M) Not applicable M1: Distant metastasis Background pathology MCN IPMN Yes No Site…......... Other………………………….. Comments Pathological staging pT pN pM (if applicable) Completely excised at all margins? Yes (R0) No (R1 /R2) Signature:…………………….….…… Date:…………………SNOMED codes: T………M……….. PUB 040510 24 V1 Final APPENDIX F PROFORMA FOR AMPULLA OF VATER CARCINOMA Surname: ........................ Forenames: ............................ Date of birth: ....…......... Hospital: .................……. Hospital no: ...............………… NHS no: .......……..…..... Date of receipt: ……....... Date of reporting:……..…....... Sex: ....………................ Pathologist: …………...... Surgeon: ……………………… Report no:..………….…... Specimen type ……………………………………………………………………………………… Gross description Length of duodenum (mm) …… Length of lesser curve (mm)………. Maximum tumour diameter (mm) …….…. Length of greater curve (mm)….…... Other organs …………………..………….. Length of gall bladder (mm) ……. Length of bile duct (mm)……... Stent in place Yes No Size of pancreas (mm)……… x ……… x ……… Type of tumour Adenocarcinoma Differentiation Well Other Moderate (specify) .……………...…….. Poor Maximum depth of invasion (T) Tumour involvement of margins Yes (R1) No (R0) Tis: Carcinoma in situ Transection margin T1: Tumour limited to ampulla of Vater (gastric, duodenal, pancreatic, bile duct) or sphincter of Oddi Dissection margin (SMV, SMA, posterior) T2: Tumour invades duodenal wall Anterior pancreatic surface T3: Tumour invades pancreas Which margins involved (specify)?................................................ T4: Tumour invades peripancreatic soft tissues, or other adjacent organs or structures Perineural invasion Yes No Lymph node involvement (N) Total number of nodes ……… Number of nodes involved ……… NX: Cannot be assessed N0: Regional lymph nodes not involved N1: Regional lymph nodes involved Distant metastasis (M) Not applicable M1: Distant metastasis Background pathology Other……………………….. Adenoma Site… Comments Pathological staging pT pN pM (if applicable) Completely excised at all margins? Yes (R0) No (R1 /R2) Signature:…………………….….…… Date:………………… PUB 040510 25 SNOMED codes: T……M…….. V1 Final APPENDIX G PROFORMA FOR COMMON BILE DUCT CARCINOMA Surname: ........................ Forenames: ............................ Date of birth: ....…......... Hospital: .................…… Hospital no: ...............………… NHS no: ......……..…..... Date of receipt: ……........ Date of reporting:……..…....... Sex: ....………................. Pathologist: …………...... Surgeon: ……………………… Report no: .………….…... Specimen type ……………………………………………………………………………………… Gross description Length of duodenum (mm) …… Length of lesser curve (mm)………. Length of greater curve (mm)….…... Length of gall bladder (mm) ……. Length of bile duct (mm)……... Size of pancreas (mm)……… x ……… x ……… Maximum tumour diameter (mm) …….…. Other organs …………………..………….. Named vessel identified Yes No Which vessel? ……………………………… Stent in place Yes No Type of tumour Adenocarcinoma Other Differentiation Well Moderate (specify) .……………...…….. Poor Maximum depth of invasion (T) Tumour involvement of margins Tis: Carcinoma in situ T1: Tumour confined to bile duct T2: Tumour invades beyond wall of bile duct T3: Tumour invades the gall bladder, liver, pancreas, duodenum, or other adjacent organs T4: Tumour involves the coeliac axis or the superior mesenteric artery Transection margin (gastric, duodenal, pancreatic, bile duct) Dissection margin (SMV, SMA, posterior) Anterior pancreatic surface Perineural invasion Yes No Lymph node involvement (N) Total number of nodes ……… Number of nodes involved ……… NX: Cannot be assessed N0: Regional lymph nodes not involved N1: Regional lymph nodes involved Background pathology Named vessel involved Yes (R1) No (R0) Yes Distant metastasis (M) Not applicable M1: Distant metastasis No Site…....... ……………………………………………………….. Comments Pathological staging pT pN pM (if applicable) Completely excised at all margins? Yes (R0) No (R1 /R2) Signature:…………………….….…… Date:………………… PUB 040510 26 SNOMED codes: T……M…….. V1 Final APPENDIX H PERIAMPULLARY CANCER DATASET MONITORING SHEET The Cancer Datasets of the Royal College of Pathologists comply with the AGREE standards for good quality clinical guidelines (www.agreecollaboration.org). The sections of this dataset that indicate compliance with each of the AGREE standards are indicated in the table. Section of AGREE standard dataset SCOPE AND PURPOSE 1. The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described. 1 2. The clinical question(s) covered by the guidelines is (are) specifically described. 1 3. The patients to whom the guideline is meant to apply are specifically described. 1 STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT 4. The guideline development group includes individuals from all the relevant professional groups. 1.4 5. The patients’ views and preferences have been sought. N/A 6. The target users of the guideline are clearly defined. 1 7. The guideline has been piloted among target users. Based on previous edition RIGOR OF DEVELOPMENT 8. Systematic methods were used to search for evidence. 1.3 9. The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described. 1.3 10. The methods used for formulating the recommendations are clearly described. 1.3 11. The health benefits, side effects and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations. 1 12. There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. 6 13. The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication. 1 Foreword 14. A procedure for updating the guideline is provided. CLARITY OF PRESENTATION 15. The recommendations are specific and unambiguous. 6 16. The different options for management of the condition are clearly presented. 6 17. Key recommendations are easily identifiable. 4−6 18. The guideline is supported with tools for application. Appendices A−G APPLICABILITY 19. The potential organizational barriers in applying the recommendations have been discussed. Foreword 20. The potential cost implications of applying the recommendations have been considered. Foreword 21. The guideline presents key review criteria for monitoring and audit purposes. 1, 11 EDITORIAL INDEPENDENCE 22. The guideline is editorially independent from the funding body. 1 23. Conflicts of interest of guideline development members have been recorded. 1 Standard 5 is currently regarded as not directly applicable to this dataset. PUB 040510 27 V1 Final